Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

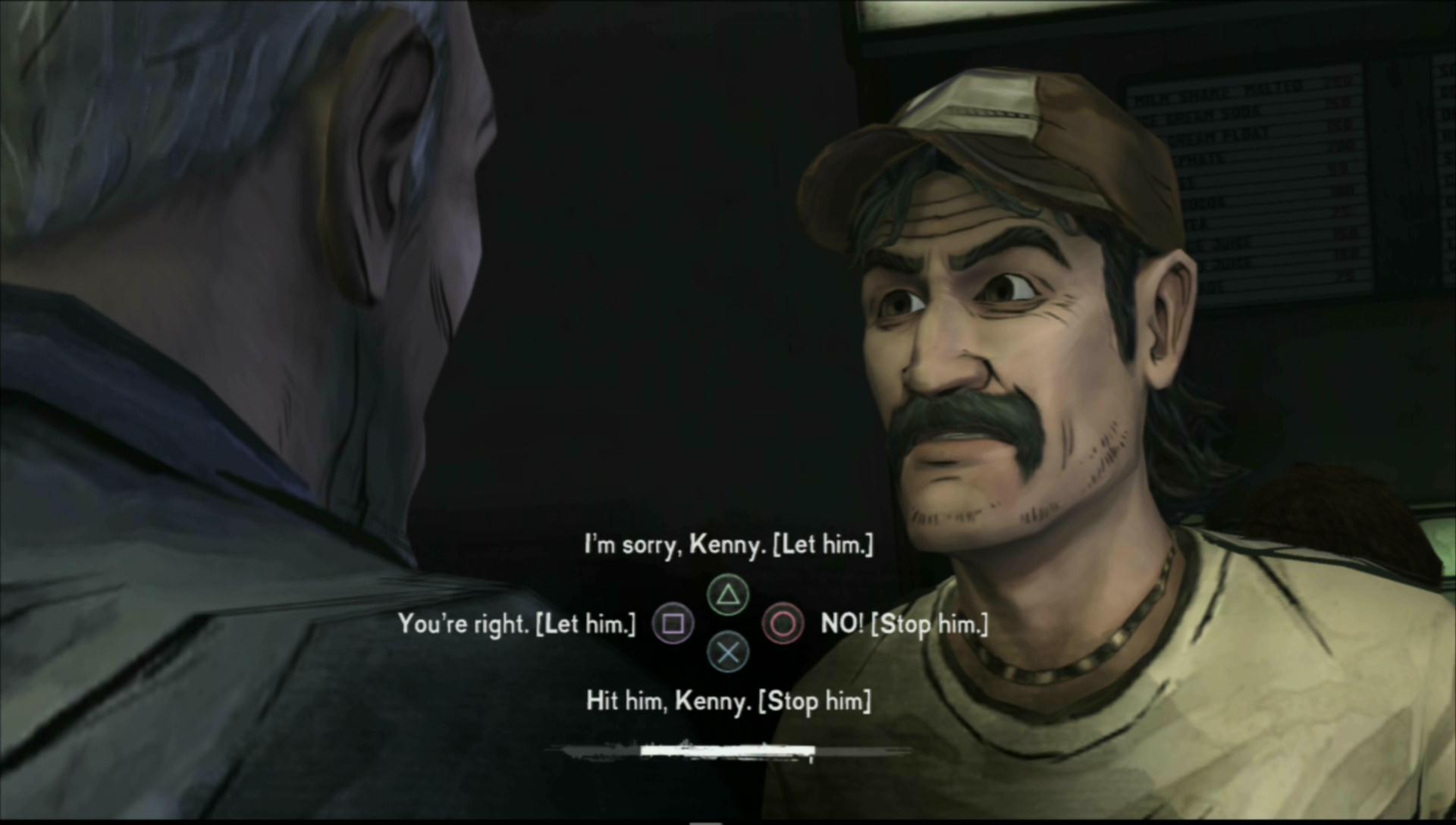

Main image: The Walking Dead games from Telltale Games pushes filmic narrative to the fore rather than fast-paced action.

There is nothing like a video game. Not in the way people say “there’s nothing like a warm bath” or “there’s nothing like home”; there is, literally, nothing like a video game. They aren’t like films, or books, or music, and yet those are the only mediums they're ever compared to.

But games require active participation, in contrast to the much more passive consumption of going to the cinema or reading a novel; they can never truly tell a story in the way other stories are told.

Films have a beginning, a middle and an end; games have all of that and a continue.

Shaping the story

With most games, the player can play differently to every other player, leaving with a unique experience and impression of what they’ve just seen. They can choose to abandon the game halfway through; they can reload an old save file; they can play it 10 times over, and each time they'll do something new, see something they hadn’t noticed before.

It’s not necessarily that games are capable of more than film, but they are capable of telling stories that affect us in different, nuanced ways.

Films have a beginning, a middle and an end; games have all of that and a continue

In a game, you're shaping the story with your own hands. The way you press the buttons sculpts the outcome – think of Telltale’s quick-time events or its timed dialogue choices, or even Breath of the Wild’s story snippets as told through Link’s memories, which can be seen in any order to give you the same story, but with different weighting based on which ones you find first and last. There’s no indication of chronology for most memories, which means you’re never quite sure what happened first, and you can create your own timeline of events that might vastly change how you see the relationship between Link and Zelda.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

The inherently role-playing nature of most games plays into how we come away from them, too. A film will ask us to empathize with the main character or characters, or at the very least to understand their motivations in some way; a game will give us the chance to be that person, to not only empathize with them but to guide their hand.

The Witcher 3 has you deciding on how moral and fatherly Geralt, the main character, should be, and which of his various paramours is more deserving of his time. The Fable games morph your character based on how good or evil your decisions are, but they still grant you the free will to decide. The landscape and the factions in Fallout New Vegas depend on how much chaos you’ve caused throughout the wasteland so far.

Fulfilling the power fantasy

Games are dominated by power fantasy, and it’s not hard to see where that came from: firstly, they are fundamentally interactive, and giving the player a controller implies that they can control. But those power fantasies also come from a learned desire to be the hero, the winner, the one who saves the world – something learned from the comic books and sci-fi films of the 80s, an era in which many of the gamers and game developers of today grew up.

But games are starting to surface that take the passivity of the cinematic experience more to heart, like Variable State’s Virginia, which has the player walking through various vignettes, experiencing a story with real-time cinematic editing, a slightly jarring experience within a game. As soon as you reach a pre-decided location, the scene ends and the next one begins. It’s rare that games take away this kind of narrative control from you, but it’s also fascinating to see how techniques borrowed from films change how we play.

Separating games from film entirely is just as unhelpful as constantly comparing them

Games like Uncharted and The Last of Us borrow heavily from films, too, but in a different way. Firstly, both are inspired by actual films: Uncharted is very Indiana Jones, and The Last of Us is a blend of multiple influences, including Gravity and No Country for Old Men. Naughty Dog, the developers of both games, is well-known for its well-written dialogue, cinematic cutscenes and dedication to photorealism, all of which are achieved and enhanced by the use of motion-capture and real actors.

Again, this is an example of how cinematic techniques are used to improve and change the face of gaming, rather than acting as some kind of opposition all the time.

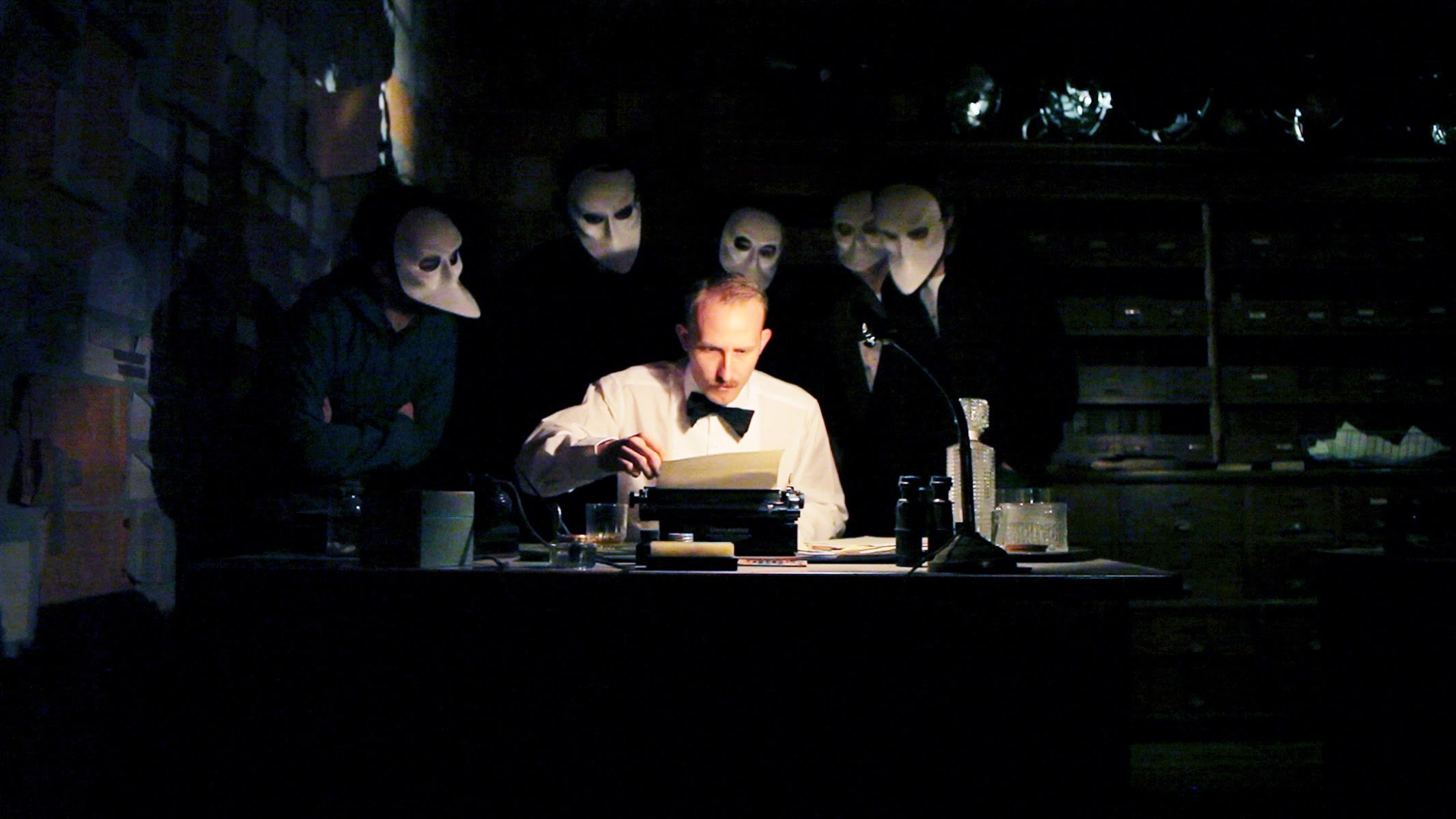

Separating games from film entirely is just as unhelpful as constantly comparing them. The two can learn a lot from each other, and use their differences to develop in new and compelling ways. We already have interactive theatre, like Punchdrunk, a multi-room experience/performance where the audience can take an active role as well as choosing which particular room they want to see. There are choose-your-own-adventure books, which give the reader the chance to influence the plot and outcomes, with increasingly complex ones also giving you an inventory to keep track of.

The limitations of cinema

But interactive film is more complicated – it’s been a passive medium for so long, designed around rooms of seated viewers in the dark. There are a few examples of interactive cinema, like Kinoautomat, which asked the audience to choose what happened next by voting, but film is incredibly restrictive when it comes to audience participation. There’s only so much they can do.

Games can be influenced by cinematic techniques, but the relationship doesn’t seem to go the other way

So where does this leave us? Gaming is continuing to expand and explore its horizons, merging with new technology to create AR and VR experiences, photorealistic faces and motion-captured acting, but its relationship with film is largely one-way. Games can be influenced by cinematic techniques, but it doesn’t seem to go the other way.

We have films that feel like games: Edge of Tomorrow, Attack the Block, Scott Pilgrim vs The World – which are in part a result of the gaming generation becoming film directors. But as the lines between interactive media become more and more blurred, perhaps we won’t need to differentiate between games and films for much longer.