Is Linux on the desktop dead?

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Since the turn of the century, pundits have been telling us that this will be the year of desktop Linux - and unless something really extraordinary happens, this will be the 11th year that it hasn't happened.

While the open source operating system has made significant inroads into the server and mobile markets, its desktop market share is much the same as it was a decade ago: about 1 per cent. Netbooks gave Linux a shortlived boost, but the world of PCs still largely belongs to Microsoft - with one Unix-spun exception.

Apple's Mac OS X is doing what Linux advocates long dreamed of - it's actually taking market share from Microsoft. Can Linux learn anything from Apple, or does open source need its own Steve Jobs? In short, can Linux win?

Simply the best

Linux's mission was simple: to make the world's best desktop operating system. If you didn't like Windows' system requirements, Microsoft's business tactics or the small print of the licence agreement, Linux was waiting with open electronic arms.

"There is a better way," the Linux people said. And eventually, consumers realised that the Linux people were right - they could move to a platform that offered an alternative to Windows. A platform where malware, spyware and other irritants weren't a factor. A platform designed to bring man and machine together in harmony.

There was a problem, though: those consumers bought Macs. The numbers are staggering. Apple's Unix-derived Mac OS X was shipped on 1.99 million Macs in the third quarter of 2010, according to IDC. That gave Apple an unprecedented 10.6 per cent of the US PC market.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Year on year, Apple's sales are up 24 per cent compared to just 3.8 per cent for rest of the industry, and that figure doesn't include iPads or other iOS devices. Why Macs and not Linux? In 2005, industry analyst Gartner said that desktop Linux was "up to five years away" from mainstream use.

Five years later, Linux still isn't there. Michael Silver, Research VP and Distinguished Analyst with Gartner, explains:

"No, Linux didn't become big on the desktop, and yes, Apple does appear to be causing Microsoft more problems [than Linux] these days. I think this underscores the issue that cheaper does not solve problems. Organisations are looking for solutions that provide value and solve their problems, and desktop Linux does not really do that when you have Windows and Office - real Microsoft Office - to run."

As Silver points out, there's a growing trend for people to influence the choice of computers they're given, "and while most can't officially select their platform yet, users want devices they perceive as increasing their productivity. And most would rather drive a luxury or sports car (the Mac perception) than the Yugo (their perception of Linux). Linux still has a perception of being unapproachable, and it doesn't have the marketing budget to buy the cachet that Apple does."

Marketing is certainly part of it - as the world's second biggest company, Apple can afford to splash out on the odd advert, and the firm enjoys press coverage that often borders on fawning. However, there's more to it than a massive marketing budget and Steve Jobs' famous Reality Distortion Field.

Perhaps the problem is that everybody who's interested in Linux is already using it.

OSes aren't interesting

To most people, operating systems simply aren't interesting - they would no more change their PC's operating system than they would change the engine in their car. Because of this, Linux faces an exceptionally difficult situation: to get significant market share, it needs to be pre-installed on shipping PCs.

Unfortunately, to be pre-installed on shipping PCs, it needs to have significant market share. Catch 22. "Yes, the OS is the unexamined part of the computer system for many people," Gerry Carr says. Carr is Director of Communications with Canonical, the creator of Ubuntu.

"Actually, it's more interesting than that," he continues. "Windows is so embedded, it's become invisible to users. Ask them to tell you something about Windows and they will start to talk about the word processor and the spreadsheet thing. Microsoft Office is actually the visible part."

Carr isn't convinced that users think Linux is a Yugo. He's not sure they have an opinion at all. "My read on it would be that Linux doesn't have an image at all among the vast majority of users," he says.

"There is a legacy, sure, of people in the industry who tinkered with it and didn't like it. And certainly within the IT industry, there are many who, from professional obligation or otherwise, hold and promote that opinion. But [if you] sit in a room with mainstream users, you'll find that they don't know what Linux is, never mind have negative associations with it."

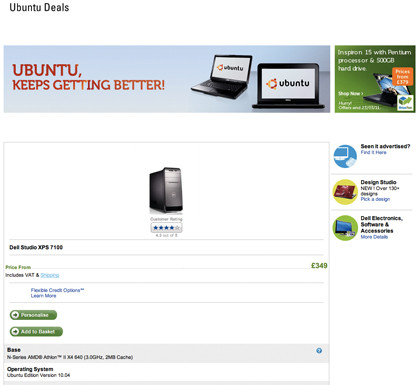

So would OEM support help? With the honourable exception of Dell, which threw its considerable weight behind Ubuntu in 2007, few mainstream consumer PC firms even acknowledge Linux's existence in the consumer sector - and even Dell's Ubuntu page is looking sparse these days, with just one Studio XPS available with Ubuntu pre-installed. You'll find Red Hat Enterprise Linux on its high-end workstations, but at consumer level it's Windows all the way.

Linux just isn't something the average computer buyer is likely to encounter. The places where mainstream users now buy their PCs - Tesco Extra, Amazon, Currys Digital and so on - are largely Linux-free. If you enter 'Linux' into the search box on PC World's website, you'll be told 'Sorry, we found no results for your search.'

To add insult to injury, the site then asks if you'd like to look at an iPad.

HP and Linux

Can Linux thrive when OEMs don't offer it? Amanda McPherson is Vice President of Marketing and Developer Programmes at The Linux Foundation, a non-profit group that aims to raise awareness of and promote the use of Linux.

"There is a lot of pressure on OEMs to use Windows, as we have seen in the netbook market," she says. "But we see traction in different areas. HP, for instance, has announced that it's shipping Linux on desktops in greater quantities than ever before. We've also seen the use of Linux as a desktop client rise with developers. We assume those kinds of use cases will continue."

The Linux HP desktop will be shipping is its own WebOS, which it acquired when it purchased the smartphone maker Palm. In March, HP CEO Leo Apotheker told Bloomberg Businessweek that from 2012, "Every one of the PCs shipped by HP will include the ability to run WebOS in addition to Microsoft Corp's Windows."

Apotheker says that WebOS will "become a very broad and very massive platform," shipping on 100 million devices per year.

State of confusion

That could be a significant step forward for Linux on the desktop. However, it could also be hopelessly confusing. As former Apple executive Jean-Louis Gassée wrote on Monday Note, the biggest PC firm's Windows portfolio might look something like this in 2012:

"Intel-based PCs and laptops running the 'mature' Windows 7. ARM-based laptop and netbooks on Windows 8. Tablets using a version of Windows 8 with a touch interface. Some, but not all, "will include the ability to run WebOS in addition to Microsoft Corp's Windows." Simple, easy to understand. Can you imagine the sneers at Apple and Google when looking at such a picture?"

"PC manufacturers will not solve all, or any, problems by shipping Linux," Carr says. "PC manufacturers will ship what their customers are asking for. We haven't generated sufficient directed and determined demand in a broad enough mainstream market to convince them to [ship Linux] in great numbers. I don't think it is going to be a supply-led revolution. It needs to be demand led, and we'll be spending considerable time boosting that."

Canonical thinks it has the solution to mainstream users' lack of interest in desktop Linux: make something that's as attractive as, or more attractive than, Mac OS X or Windows 7 - to borrow Michael Silver's analogy, make a sports car rather than a Yugo. Canonical calls its sports car Unity.