Is Linux on the desktop dead?

Unite and take over

Unity is the new interface for Ubuntu, and it's a deliberate attempt to bring good looks and user-friendliness to a platform that isn't exactly famed for its fantastic user interface design.

It's proved controversial; it was developed in-house, not by the wider community, and it's very different from earlier versions of Ubuntu and other GNOME-based distributions. By betting the farm on Unity, Canonical could alienate some of its existing user base in the hope of attracting lots of new users.

It's the Apple model: instead of asking customers what they want and then trying to meet every single request, Apple simply creates what it thinks works best and then releases it.

"You can't just ask customers what they want and try to give that to them," Steve Jobs said in 2005. "By the time you get it built, they'll want something new."

It's a big risk, but Gerry Carr for one is bullish. "We are trying to do something that has never been done before," he says. "We have taken the evolution of Linux as a mainstream OS further than anyone else; by any reasonable estimation, it's already the third biggest operating system in the world. Unity gives us the chance to arm [users] with a look, feel and experience that will enable them to convert other users to the benefits that they enjoy.

"I think it will be the first time you have someone who looks at a Linux-based OS, if you want to describe it that way, and see it on looks alone as something they want to use. That's a true first and we think it has the potential to shift the market."

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

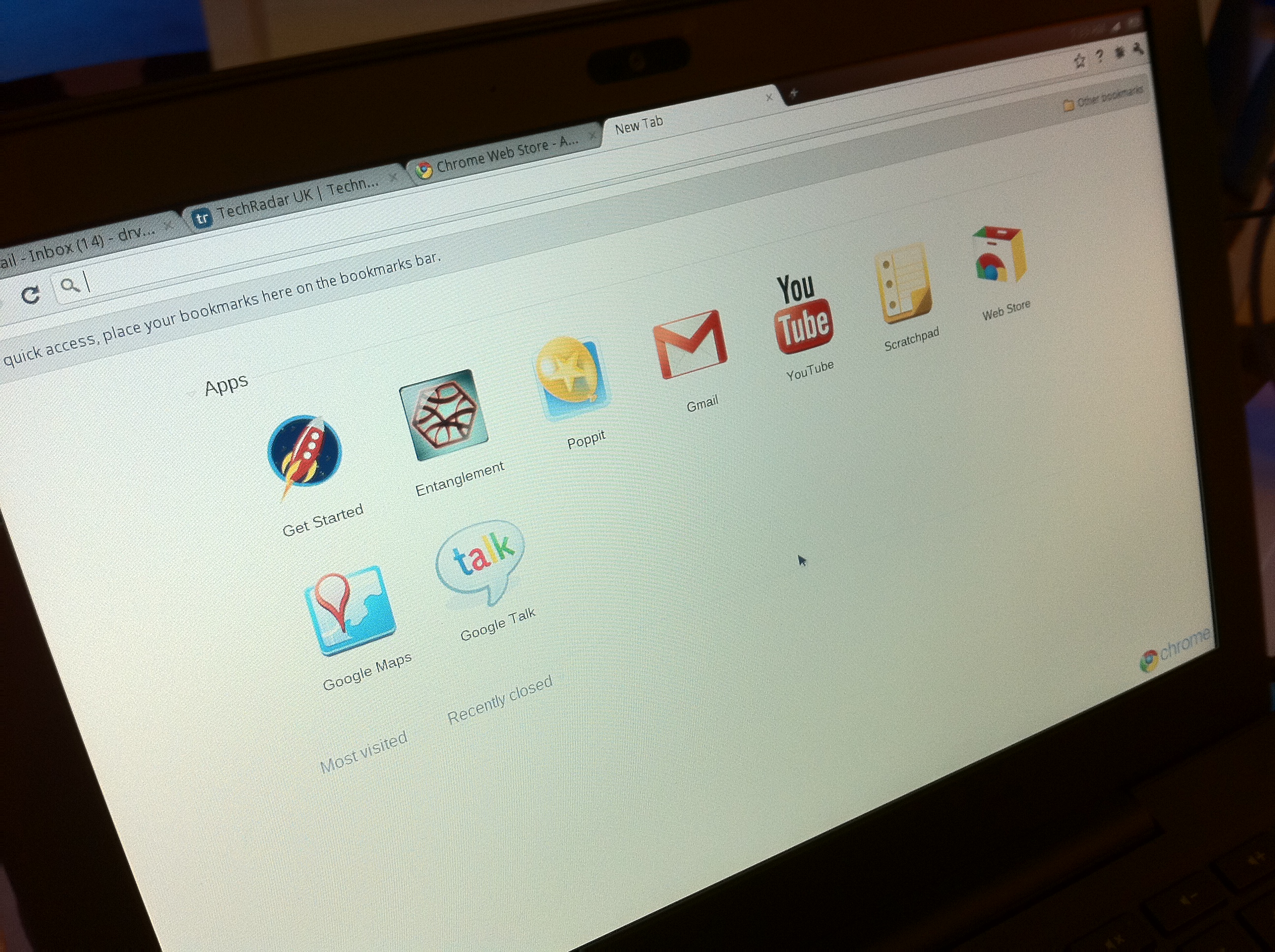

Canonical isn't the only firm that thinks a more user-friendly Linux could be a big deal. Google has Chrome OS, a Linux-based operating system for netbooks, which is due for release this year.

Rise of the robots

Can Linux win? In the form of Android, it's winning already. Smartphones now outsell PCs, and as our computing becomes increasingly mobile, we're more likely to use an Android device than a Windows one.

"I agree, a traditional desktop is becoming less and less the primary computing environment that people interface with," Amanda McPherson says, adding - with some understatement - that "Linux is doing quite well."

According to Canalys, in Q4 2010, one in three smartphones ran Android. Google's platform had 32.9 per cent market share, Nokia 30.6 per cent, Apple 16 per cent and RIM (BlackBerry) 14.4 per cent. Microsoft trailed far behind with just 3.1 per cent.

Android is growing in the tablet market too. Apple's market share has gone from 95 per cent to 75 per cent, and many Android-powered rivals have yet to ship. Strategy Analytics predicts that Apple's tablet share will drop below 50 per cent by 2013, with Android doing most of the damage.

The mobile market is very different from the PC market, and Android owes its success to those differences. Windows isn't dominant on mobiles, and Android isn't a software-only proposition: Google doesn't have to persuade people who buy an HTC Desire HD to switch OSes, because the HTC ships with Android preinstalled.

In fact, you could argue that Android is mainly about hardware; you choose Android because of the device first and the operating system second.

False dawns

Android looks as if it could represent the ultimate triumph of Linux over Windows, but we've been here before and it didn't end well.

For a while, netbooks seemed like the Trojan horse that would let desktop Linux sneak into the mainstream. In 2007 and 2008, netbooks ran Linux. Windows XP was being retired and Vista was too big and costly to be worthwhile on cut-price machines. By the end of 2007, Asus had shipped around a million Eee PCs, all running a customised Xandros Linux.

Other manufacturers followed: Acer with Linpus Lite, Dell with Ubuntu, HP with SUSE and so on. It wasn't long before Microsoft noticed, and with Windows 7 some way off, it hastily resurrected Windows XP and offered PC firms big discounts.

By December 2008, nine out of ten netbooks on sale were running Windows; today, most shipping devices run Windows 7 Starter Edition.

What happened? Lenovo's Matt Kohut told Tech.Blorge, "There were a lot of netbooks loaded with Linux, which saves $50 or $100 or whatever it happens to be… [and] there were a lot of returns because people didn't know what to do with it. Linux, even if you've got a great distribution, still requires a lot more hands-on than Windows. So we've seen people wanting to stay with Windows, because it just makes more sense - you take it out of the box and it's ready to go."

There are several reasons why that bit of history seems unlikely to repeat itself, though. Firstly, and perhaps most importantly, Microsoft doesn't have a familiar OS it can resurrect to fend off the Android horde: Windows Mobile never had the traction Windows had on the desktop, and by the time Microsoft canned it in 2010, it was looking hopelessly outclassed.

The new Windows Phone is a vast improvement, but OEMs aren't embracing it the way they did Windows on netbooks - and Windows Phone's market share is falling, not rising.

According to ComScore, Microsoft's share of the US smartphone market dropped from 9.7 per cent to 8 per cent between October 2010 and January 2011. Microsoft claims to have shipped - not sold - 2 million Windows Phone devices during that period, but so far at least it doesn't appear to be stopping the decline in Microsoft's mobile market share.

The much-hyped deal with Nokia to make Windows Phone the Finnish firm's platform of choice may address that, but not in the short term: the first Nokias running Windows Phone may not arrive until 2013. By then, Android could well be dominant.

Tablet woes

If things look bad for Microsoft in the mobile market, tablets must be making it downright miserable: as with netbooks, the rise of the tablet appears to have taken Microsoft completely by surprise, and there isn't an OS to put on them.

With the exception of a few devices like the Asus EP121, firms are choosing Android to compete with Apple. Windows 8 will be tablet-friendly, but it isn't due until 2012.

If you take the smartphone and tablet markets together, you'll see that traditional roles have been reversed. Here Microsoft is the minority player, and most of the mobile market is split between two Unix-derived operating systems: Apple's iOS and Google's Android.

That's unlikely to change in the short term, and it could have long term effects too. "I think these changes have made people aware of a couple of things," Carr says. "First, that the choice of OS matters - this awareness is on mobile devices, not necessarily PCs - and secondly, that the choice need not be provided by Microsoft. That's critical to opening up the world to some genuine competition based on quality of the computing experience, not ability to dominate the supply chain."

That doesn't mean Android's success will necessarily translate to desktop computers, though. "I've been surprised by how little bleed there has been from the mobile devices to the fuller PC experience," Carr says.

"Android's success on smartphones doesn't pre-suppose success on netbooks, for instance. The main driver of that will be marketing and delivery […] the success or failure of WebOS as an instant-on product, Chrome as a cloud netbook OS or Android as a phone OS will have little effect on the success of Linux or any other OS in the core PC market […] we aren't going to get a free ride onto people's primary machines because of the choices they have made on their tablets and phones and other devices. We still have to work hard to convince users and the industry of the value of an alternative."

The success of Android and iOS could help desktop Linux indirectly, though. Smartphones and tablets are helping usher in what Steve Jobs calls "the post-PC era", where always-on mobile devices connect to the cloud.

The growing capability of HTML5 and runtimes like Adobe AIR mean the underlying OS is becoming less important. "Android, Chrome OS and WebOS tablets running Linux are poised to become an important part of the 'desktop' equation," McPherson explains. "It just may not look like what we today consider to be the desktop."

HTML5 introduces important features that let browser-based applications act like stand-alone software, and browsers are evolving alongside it: the latest versions of IE, Chrome and Firefox include hardware acceleration, which uses your graphics card to deliver better in-browser graphics and video.

Over time, HTML5 should enable developers to provide in-browser applications as good as, or better than, traditional desktop software.

Three screens

Microsoft's vision of 'three screens and the cloud' is nearing reality, although those might not all be Microsoft ones: provided your browser can handle HTML5, it doesn't matter what the underlying OS is.

"I think there will be a range of low cost, small screen PCs that will be popular, emerging on a range of architectures," Gerry Carr says. "I think there will be a critical mass of Linux use as a technology that will bridge mobile devices, PCs and cloud computing."

That won't be a single flavour of Linux - it will be a cocktail: Ubuntu on a desktop, Android on a tablet, a sprinkling of WebOS and a dash of Chrome OS too. "The platform environment today isn't a zero sum game,"

Amanda McPherson says. "Since Chrome uses Linux, if Chrome does well it benefits the Linux platform - just like Android or WebOS. Since Linux is used in so many ways by so many companies and projects, it doesn't make a lot of sense to focus on one application."

The future of Linux is on tablets, smartphones, PCs and perhaps devices still deep in development. "This is desktop Linux," Carr says. "It's just that our desktops will work and act differently."