The evolution of 3D games

Once upon a time, a handful of pixels madeth the space invader. Graphics were iconic, not representative: a picture on the box or manual showed you what it was meant to look like, and your mind filled in the necessary gaps.

Nobody could have predicted that in just 20 years, we'd be immersing ourselves in realistic living cities, flying over gorgeous tropical islands and going head-to-head with astoundingly rendered characters – and not even being particularly impressed.

But in years to come, modern games like Grand Theft Auto IV and Crysis will look just as dated as the classics we remember from the days of yore. In fact, they'll probably look more so: while the simplicity of a retro game's look has a certain charm to it, old 3D titles tend to flat-out look old. Try almost any hit game of the mid-to-late '90s for proof of that.

3D is about more than just pretty graphics. Done right, it makes gameworlds come alive. A 2D sprite can only do what it's been drawn to do, while a 3D character has a complete endoskeleton and can respond naturally (at least in theory) to anything that happens – the classic example being 'ragdolls', where a fallen enemy doesn't simply slump to the ground in a canned animation, but tumbles off the railing and lands with one arm draped over a step.

You can create worlds rather than merely levels, unlocking the player's ability to truly explore and experience the world as the character would. You can build simulations ready to be poked and prodded, abused and enjoyed. It's phenomenally powerful, to the point that many nominally 2D games are now really 3D ones viewed from a locked perspective, so that they can better use the possibilities of animation, physics and art assets.

Why render hundreds of frames of animation you may not be happy with when you can make a model and keep tweaking it until it's perfect? You may lose some of the old-school charm, but you gain far more.

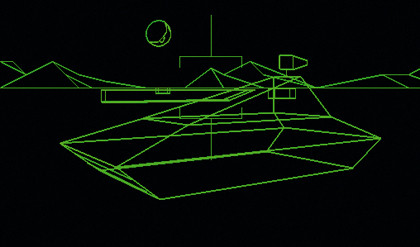

Battlezone

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

The first big 3D success was Battlezone, a tank game released in 1980 that used vector graphics to create its work, much like Asteroids. While a simple game by modern standards, it was fiendishly complex for such an early example, offering the ability to go anywhere in an (admittedly featureless) world, hide from attacks and fight enemies.

TANK WARFARE: Battlezone was thought so realistic that the US Army used it to train tank gunners

Not impressive enough? In 1987, the first Freescape game, Driller, hit the shelves. It offered a full 3D world on platforms as basic as the Spectrum, and was an actual game rather than just a tech demo. Next to that, it didn't matter that it was ugly, the frame-rate was abysmal and the game itself wasn't actually much fun – it got lots of attention.

The Freescape engine in its various forms was used in several famous releases, including Castle Master and its sequel, and the all-out 3D Construction Kit. Legend has it that someone somewhere once made something other than a surreal, unplayable mess in this, but we never saw it.

Freescape also made it onto TV, in the form of the absolutely atrocious Craig Charles vehicle Cyberzone, one of the most toe-curling attempts at creating a games-related TV show ever. Thankfully, all that remains of it is a single YouTube clip – and that's painful enough.

Most of the early 3D games stuck to simpler technologies. These days, we think of 3D as free-roaming, real-time engines, but back in the day, simply getting a game to look 3D was impressive.

As early as 1981, games were achieving this feat – 3D Monster Maze was terrifying a generation with its slowly updating screens and roaming T-Rex, and the first Ultima game was offering a very advanced hybrid of block-by-block movement 3D graphics for its dark dungeons alongside a topdown 2D overworld for exploration.

Interestingly, while most developers kept pushing further towards 3D, Ultima ended up pulling back, switching entirely to a top-down sprite-based system for the series' glory days. The 3D element later developed into its own spin-off – the Ultima Underworld games – before returning for the series' sadly disappointing final outing – the buggy, system-murdering Ultima IX: Ascension.

Faking it

The problem has always been the same: the potential of 3D fights with the limitations of current systems, whether it's simply displaying the graphics in the first place or making them look as good as other art styles.

Going back to an early '90s 3D game now is almost painful. Flat faces, non-moving lips during conversations, stick-figure character models, smeary textures and appalling animation... the list of problems goes on.

Some games got past this, sometimes bizarrely – most obviously Core Design's legendary heroine Lara Croft, who managed to become an international sex symbol despite looking like a pointy-chested Pinocchio. Most survived simply because playing a 3D game felt futuristic, even if the lack of polygons our PCs could push out meant that 2D games were usually much more detailed.

TOMB RAIDER: The realism of the, ahem, gameworld has certainly come on

For much of 3D's history, the trick has been getting the effect of the third dimension without having to do it for real. The early Wing Commander games gave the illusion that you were flying through 3D space, but really they were just scaling sprites up and down.

In first-person shooters, it quickly became clear that walls were easy thanks to their incredibly simple geometry, but snarling hell-beasts dripping blood from their fangs were asking a bit too much. So developers compromised.

The worlds themselves were made in 3D, initially just as mazes. Then, as texturing became more advanced, more realistic-looking areas were created, like those in Catacomb 3D.

Interestingly, the state of the art varied dramatically across genres. Shooters had to be fast and fluid, so they were kept simple. In the case of early games like Core Design's Corporation, things were stripped down so much that the engine didn't even bother with textures.

Id's first breakout hit – Wolfenstein 3D in 1992 – had textures to depict the inside of its supposed Nazi castle stronghold, but all the maps were completely flat and the interaction was limited to just opening doors and shooting enemies. Ultima Underworld, which came out in the same year, had sloped surfaces, advanced lighting effects, dialogue, puzzles, magic systems, physics, 3D objects, a real plot, the ability to look up and down instead of having your view locked straight ahead and much more.

TRADE-OFF: For the Ultima Underworld games, the payoff for this level of 3D quality was poor performance and a small viewing window

Ultima Underworld could afford to push these limits because as a role-playing game, it was inherently slower than a shooter, and the audience was more willing to accept the necessary limitations, like the small viewing window. It didn't hurt that while publisher Origin's official motto was 'We Create Worlds', its unofficial credo was 'Your PC Will Cry'. It never did worry about system requirements...