Star Trek: Bridge Crew proves that VR has a bright multiplayer future

"Can we scan for survivors?"

There were many standout moments from my time with Star Trek: Bridge Crew, Ubisoft’s virtual reality foray into the world of Star Trek. But the one that’s stuck with me the most was one that could have only happened in VR.

Despite the best intentions of the team at Ubisoft, we decided to jump into the game with as little instruction as possible, to get the most realistic responses possible.

Naturally this meant that our first mission in the game was an absolute shambles. I was the ship’s pilot and could barely steer, and the rest of the team had absolutely no idea what we were actually meant to be doing.

Being a bit crap in multiplayer games is nothing new, but what was remarkable about Bridge Crew was how this translated into the visible body language of the other TechRadar editors playing alongside me.

Thanks to a combination of the hand tracking from the Oculus Touch controllers and the head tracking from the Rift itself I was able to see Gerald Lynch hold his upturned hands out in exasperation, and James Peckham peering at his control panel, trying to find the right control for the job.

Being able to read my colleagues like this made me feel like I was actually in the room with them, a feeling that was only marginally undermined by the fact that for the purposes of the press event we were actually in the same room as one another.

Four players, one ship

But let’s take a step back for a moment.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

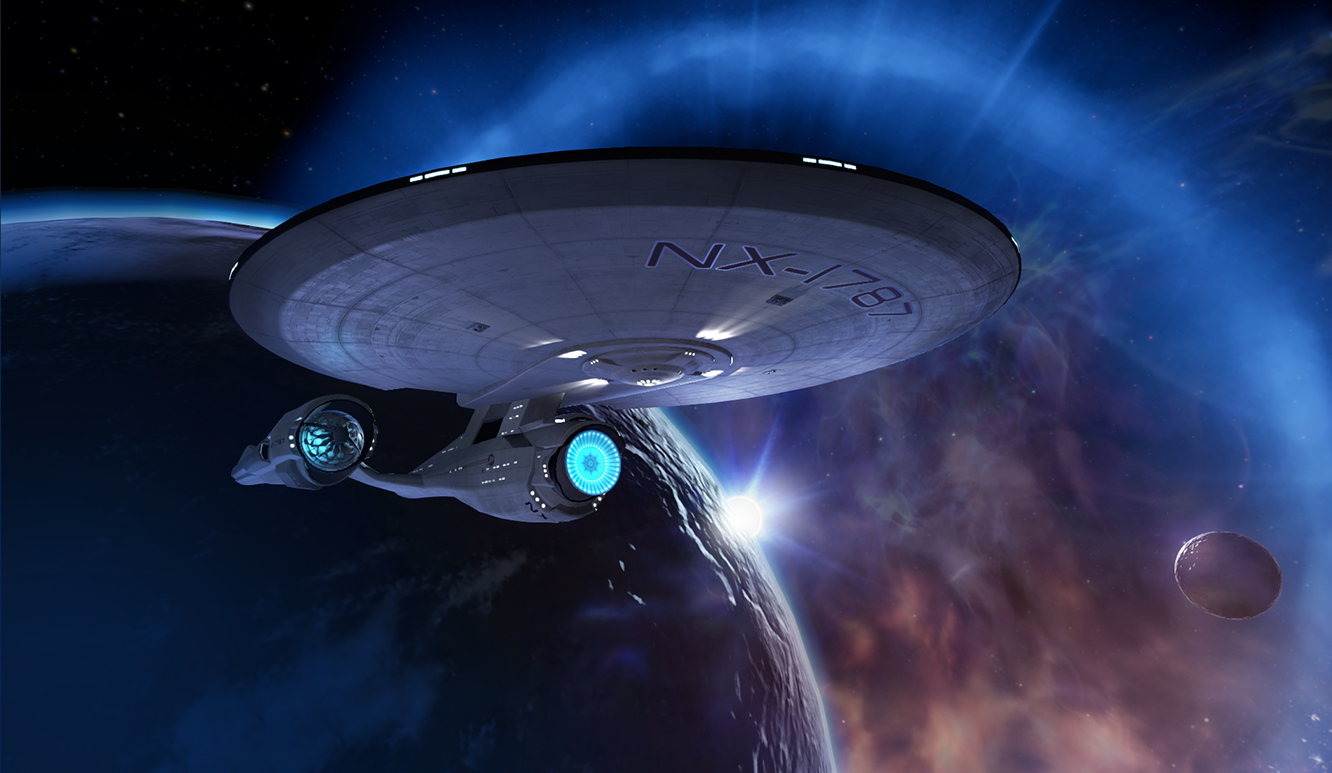

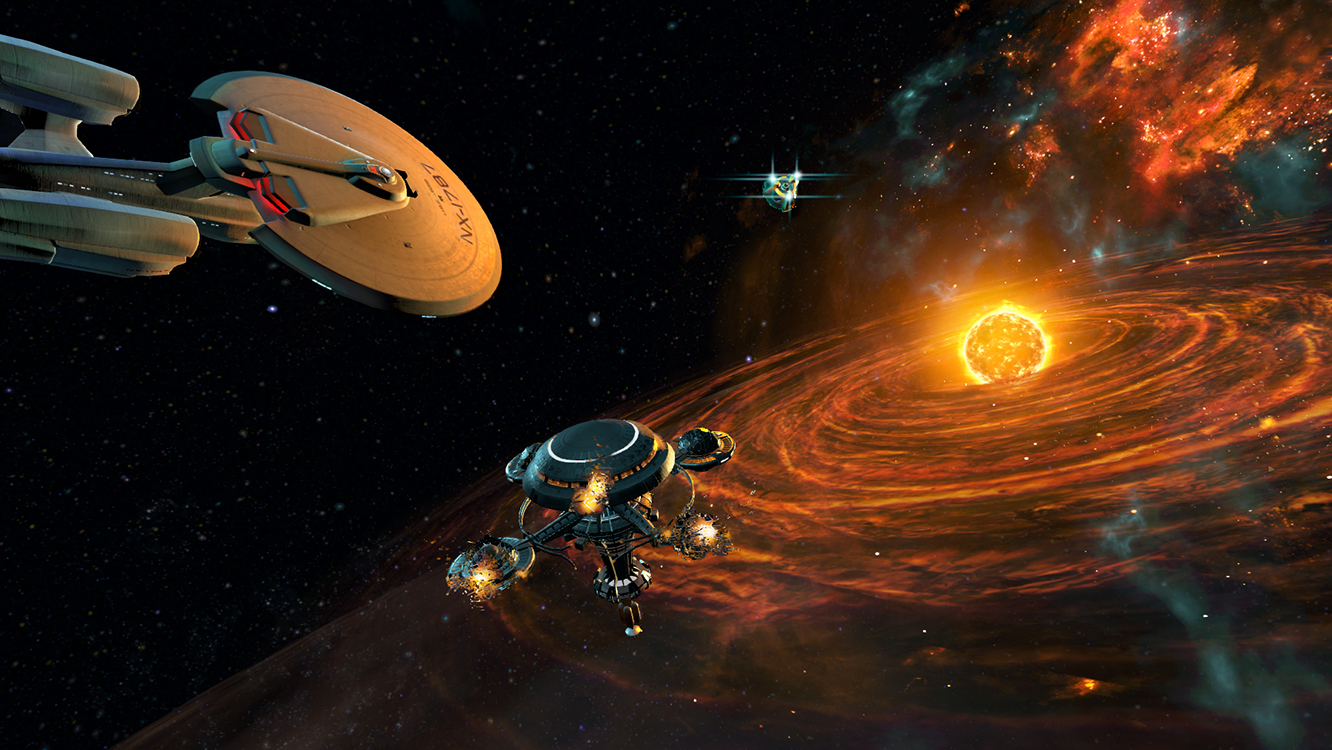

First revealed at Ubisoft’s E3 2016 press conference Star Trek: Bridge Crew is a multiplayer virtual reality game set in the Star Trek universe. Four players take on the role of the eponymous bridge crew, attempting to pilot a classic Star Trek ship, battling Klingons and rescuing allies.

Each player has a distinct role within the team. The pilot (think Lieutenant Sulu) is in charge of steering the ship and gets to pull the cool warp-inducing lever. Meanwhile the player in the tactical seat (Chekov in the original series) controls the ship’s weapons, shields, and targeting.

There’s an engineering role which involves assigning power to the ship’s different systems (when they’re not doing their best Scottie impression), and finally a captain gets to command proceedings from the rear, as well as having control over the ‘red alert’ alarm.

The mission we played had us warping into the remnants of a massive space disaster, hoovering up survivors who’d jettisoned in escape pods, and fighting off any Klingons that decided to try and mess with us.

If you’ve played the smartphone game ‘Space Team’ you’ll have a pretty good idea of how the game works. Everyone has access to different parts of the ship’s controls, and it means that you need to constantly communicate to make sure that the engineer, for example, knows to give you enough power to fly the ship when you’re trying to escape, or to beef up the shields when the Klingons come knocking.

Couch multiplayer over the internet

When we played the game we were in the same room together, but when released this will be a multiplayer game that you’ll have to go online to enjoy fully.

The weirdest thing about the experience was just how much the game felt like a couch gaming experience, despite it being online.

When something happened in the game that amused one of us, we’d use the touch controllers to point to it and when we were victorious we’d wave our arms in the air in celebration. We were in constant audio communication with each other thanks to the built-in microphone in the headset, and when each of us spoke the game animated our avatar’s mouths to make it look like we were speaking.

It felt like we were in the same room, but we could have been hundreds of miles away from one another.

After Mark Zuckerberg’s Facebook acquired Oculus in 2014 for $2 billion, the Facebook CEO has repeatedly taken to the stage to declare that the future of virtual reality is social.

Having had the most fun in VR playing games like Job Simulator and Elite: Dangerous, Zuckerberg’s statement has always felt weird to me, but Star Trek: Bridge Crew is a game that works precisely because it’s a social experience.

Individually each player isn’t doing anything that complicated. The gunner is waiting for the ship’s weapons to reload and is then firing them, and the pilot is doing little more than steering and managing the ship’s speed.

The fun in the experience came from having to work together as a team, from having to wait for the perfect moment to activate the shields after the engineer had successfully beamed everyone aboard, or jumping to warp at the exact moment that your captain gives you the all clear.

Stranger danger?

But this raises a difficult dilemma, and that’s just how fun the game will be when played with strangers.

There are plenty of VR headsets out there at this point, but it’s unlikely that you’re going to have three friends with them, meaning that you’ll probably end up playing Star Trek Bridge Crew online with people you don’t know.

If my time with the game was anything to go by, the amount of fun you’ll have is directly proportional to how able your team is to work together.

This isn’t Call of Duty where everyone can work as individual players who just happen to be on the same team, this is a game where control of the ship is literally split across four players, and you won’t get anywhere if you’re unable to work together.

With three friends, Star Trek: Bridge Crew is one of the most enjoyable co-operative games I’ve ever played, period.

But with three strangers, or even (heaven forbid) AI filling in for real players, the game’s seams might start to become more obvious.

We’ll have to wait until the game is available in the wild before we’ll know how well it works in practice, but with a delay announced by Ubisoft just days after our preview it might be some time until we find out.

- Check out our list of the best VR games.

Jon Porter is the ex-Home Technology Writer for TechRadar. He has also previously written for Practical Photoshop, Trusted Reviews, Inside Higher Ed, Al Bawaba, Gizmodo UK, Genetic Literacy Project, Via Satellite, Real Homes and Plant Services Magazine, and you can now find him writing for The Verge.