How Sony taught me to stop murdering companions and love the NPC sidekick

With a little help from my friends

It wasn’t that many years and bits ago that ‘companion’ was a dirty word in videogames. The promise of being tethered to an NPC filled me with dread. Even in the PS3 and Xbox 360 era, a companion usually exposed itself as one of two things: at best, inept fire support from a character who mostly faced in the right direction; at worst, the protectee in a - shudder - escort mission.

If you really wanted to see a game in the mid-2000s crumple to its knees with a guttural heave of gears and motor oil, conscript a side character to your cause and marvel as they jog into battle, pull out their weapon, put away their weapon, heal themselves for no reason, then wedge themselves in a doorway. Forever.

Companions are still a few fries short of a Happy Meal, but at least in this console generation they’ve moved from being a hindrance to guardedly welcomed company. And it’s Sony which has best rehabilitated them, through its PlayStation exclusives.

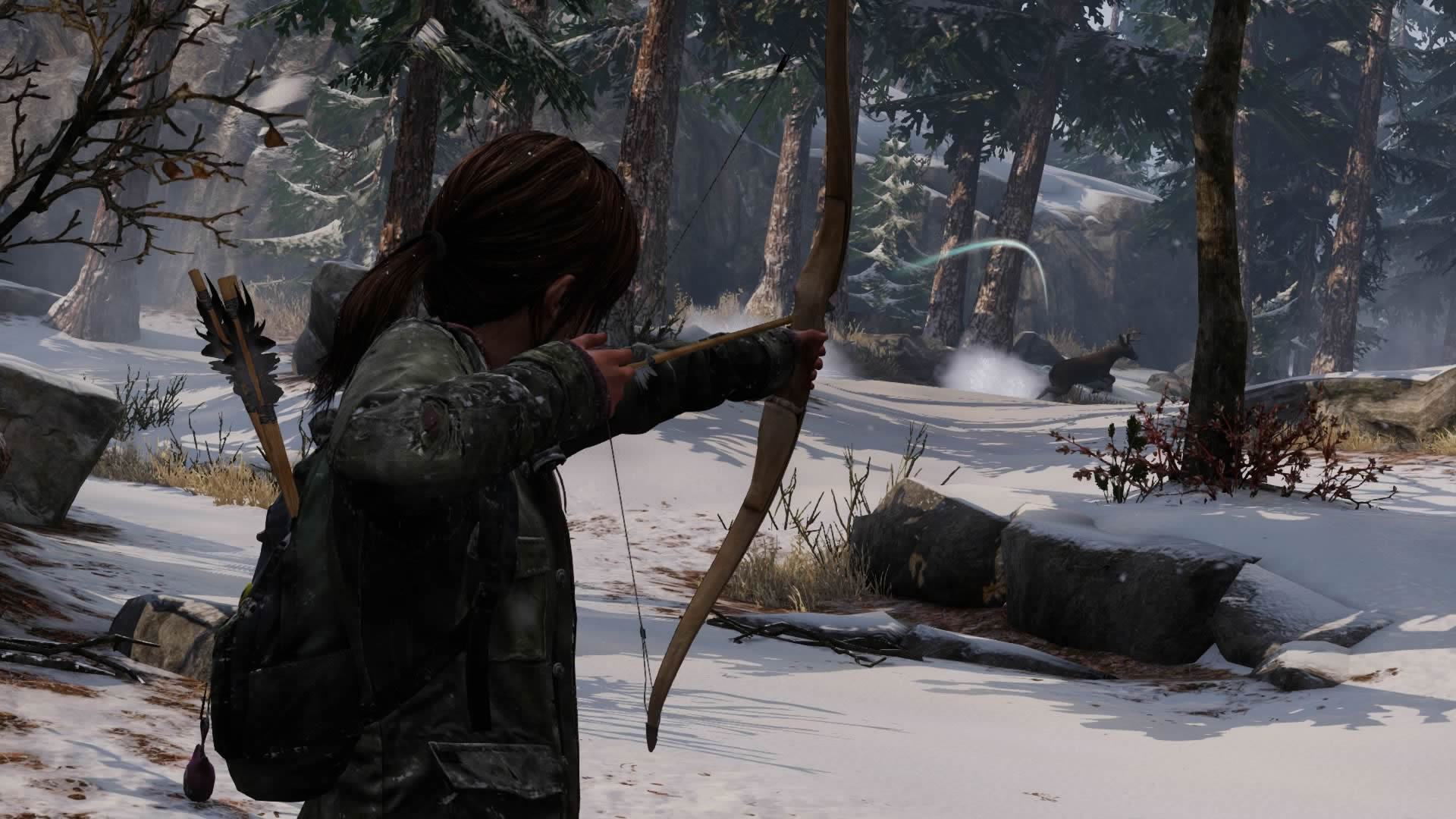

Ellie, your sparky and sarcastic teenage ward in The Last of Us, was a turning point. A mixture of clever storytelling and competent AI that built a father-daughter relationship in between moments of stabbing zombies in the eye. 2018’s God of War tried to foster a similar unlikely bond between Kratos (albino God-rilla) and Atreus (pubescent history nerd). Most recently, Days Gone squeezed both brotherly and romantic love into one weather-beaten motorbike satchel.

These three games are wholly different experiences, but there’s a narrative throughline that unites them: responsibility. And also zombies, to a lesser degree.

Burden of Bill

A companion in a videogame has to keep a lot of plates spinning. As in any story, there has to be a point to their being there. They need an arc of some sort. They need to change, somehow, as your character does - whether you have a choice of actions or the writing tricks you into feeling like you’re growing with your protagonist.

But unlike their counterparts in other media, they also have to react to the things you do: no matter how stupid or obstinate. They need to hold their own in challenging situations.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Nothing sours a relationship quite like a ‘Game Over’ screen appearing when you’re at full health, henpecking you that, ‘Bill died’. Or the more creepingly entitled admonishment, ‘You failed to protect Bill’. Or the very limpest of videogame fail-states: ‘You went too far away from Bill’, like you lost him in a supermarket and he’s been found crying by the self-checkout. Screw Bill. Game developers: you can never go far enough away from Bill.

"If Bill decides the best reaction to a zombie horde is to rout it from the centre with a bent set of salad tongs, why should you have to live and die by that decision?"

Bill in all his forms is an obvious way of compensating for AI that can’t be trusted to follow the whims of every mercurial player. But they’re sloppy solutions that put gameplay above character-building. There are other solutions that are arguably worse - the way Bethesda’s Fallout and Elder Scrolls companions can get belted off a cliff by a dragon or a nuclear hand grenade and recover after a minute-or-two’s sit-down is the coppiest of cop-outs there is - but they’re all the more irksome because you’re being punished for what is usually an NPCs incompetence.

If Bill decides the best reaction to a zombie horde is to rout it from the centre with a bent set of salad tongs, why should you have to live and die by that decision? The moment you start worrying for a character’s safety because you’ll be booted back to a checkpoint - rather than because you, you know, want them to be safe - is the moment a character turns from flesh and blood into ones and zeroes.

The Ellie method

Sony has attacked this problem from multiple angles. In The Last of Us, Ellie reacts to danger by jumping on its back with a knife and shanking it, or (if sneaking) turning magically invisible to everyone in the room except you. In God of War, your son, Atreus, is actually magic and can take almost infinite thumping by Norse monsters without ruffling his mohawk. And Days Gone (mostly) either segregates its NPCs from its zombie hordes behind fences and walls or puts them on motorbikes full of guns.

They’re three distinct methods that, critically, don’t rely on companions seriously fending for themselves, but merely create the illusion that they are. They don’t all work all the time, but as experiments they’re commendable efforts in creating sidekicks you don’t want to murder or dump in the nearest bin to protect them from their own ineptitude (which we’ll call the ‘Resident Evil 4 Solution’).

The Ellie method works because it’s clear from cutscenes and comments in quieter moments that, as a character, she’s vulnerable. Not weak, but not an unkillable god-child (like Atreus - who we’ll get to). Out of gameplay, she reacts the same way as protagonist Joel does to a screeching horde of fungus-people - by swearing lots and running away. She is, also, just a kid: with a childlike fascination with giraffes, a teenage skepticism of a world that once contained ice cream trucks and one particular outburst where the mask slips and we see that the defining moments of her life have been loss and death.

We can overlook that when we’re controlling Joel, Ellie is rarely in any actual danger, because the story beats show threats to her on two fronts: Ellie the NPC being chased by monsters, and Ellie the child disappearing in a monstrous world.

Atreus angst

For contrast, God of War’s Atreus (your experience may differ) is an example of how to take that same approach, badly. Atreus is the anti-Ellie: a parallel universe Ellie that looks superficially the same but reveals itself as a improperly-programmed Stepford child. In a weird reversal, Atreus only skulks about in cutscenes - and only when scolded by his growling bodyguard-cum-pack-mule dad, Kratos. In a fight, what he makes up for in enthusiasm he lacks in ability, which in turn he makes up for by doing lots of high-pitched shouting - usually about how nearly dead you are.

He’s also a reverse image of Ellie in that, in a world of Norse mythology far removed from whatever Kratos left of ancient Greece, Atreus is the authority. A swot, if you’re being unkind. He knows all the gods. All the stories. He even speaks Rune. Paired with a lumbering, retiree God of War - who’s been Metal Gear Solid 4-d into a state of wheezy dad bodish-ness - it’s a relationship that strains, then grates. Every. Bloody. Door in ancient Scandewegia is locked with a riddle rune or a birdbath of magic sand that Atreus has to translate or poke at, while Kratos (you) looks about impotently for something to smash with his axe.

I’ve tried to think of something nice to write about their dimension-hopping, mountain-climbing escape-the-room, but questing with this pair feels like being stuck with the two worst people on a European stag weekend: the one who knows the names of all the cathedrals and insists on ordering off the locals’ menu in an accent that’s probably racist, and the guy who takes his shirt off at the start of the night and ends up punching a policeman.

But if The Last of Us and God of War are two sides of the same coin, Days Gone is the third side. Strange. Unexpected. Not legal tender. Yet somehow brave and brilliant.

No more Mr. Nice Guy

While The Last of Us and God of War succeed or fail on what is linear storytelling, Days Gone protagonist Deacon St. John has to juggle all the same plates (still spinning) while navigating an open world: doing in bandit camps, looting houses, picking flowers for RPG-crafting-herbology - the lot.

This is where open-world games usually lose grip on story and motivation. You’ll abandon a glorious Far Cry revolution to hunt leopards or go paragliding. You’ll reschedule the Joker situation ‘til tomorrow to flap after Riddler trophies as Batman. In Fallout 4, you will forget your abducted son’s name five minutes after you leave the Vault, and that he exists at all in the first half hour.

But not in the zombie-road-movie-world of Days Gone. Days Gone’s masterstroke of writing is so simple. So elegant. Like Tinder, bread knives and probably the comb, it’s a solution so perfect and seemingly obvious that you can’t help but wonder how nobody thought of it before.

"Bend Studios hits the nail on the head through the nut and into the coffin on the first swing."

The radio chirps. Deacon clicks it on. Some local incapable yells that someone’s gone missing or they need someone murdered or that they know something world-savingly important about the plague of not-zombie Freakers terrorizing wasteland Oregon, and want him to do something. It cannot be stressed how important it is that Deacon do this thing immediately (although they’ll certainly try).

To which Deacon nonchalantly replies: “Maybe/probably/at some point/if I can be bothered.”

How has it taken the AAA game scientists this long to crack the open-world-quest-giving-quest-doing formula? Decades of side-questing, weapon-crafting and flower-picking while the lives of our assigned plot devices hung in the balance, and Bend Studios hits the nail on the head through the nut and into the coffin on the first swing. Open world players are always going to behave in ways that, narratively speaking, make them look like dicks. So why not let them roleplay as a guy who is - much as I love him - a massive dick?

Friendship formula

Early in Days Gone, your motorbike gang buddy, Boozer, gets badly injured. You put him to bed to sleep it off. He could probably use some medicine, but - meh - he’ll probably be fine. You’ll get to it. Meanwhile, you’re half-heartedly looking/mourning for your dead wife. But she’s dead - she doesn’t need more mourning right this second. Or at all. Get to it if and when you can be bothered. In the meantime: raid this bandit camp and paint your motorbike.

You’ll do all these quests eventually, of course. Because as you faff about in the post-apocalyptic biker wasteland, Days Gone’s writing will push its claws through your leathers and into your soul. NPCs will radio you and slowly, subconsciously, you’ll decide for yourself that they’re worth your time and investment. There’s no stick: no-one dies if you don’t screech into camp with the Advance Plot Macguffin just in time.

Days Gone, like The Last of Us (and God of War, too, if you can overlook its estranged-father-son Odd Couple dynamic) is carrots all the way down. Do something nice for a person, that person is nice to you back, repeat until you realize six hours later that you’ve accidentally become a better person.

Sony, obviously, isn’t the first or only developer to work that feeling of attachment to what is, stripped down, a magic trick of pixels, semi-reactive code and pre-recorded dialogue. But as de facto winners of the last console war, and in putting characters and relationships front and centre in its biggest hitters, it’s pinning down a formula for mainstream games that evokes more than a contractual obligation to care about NPCs that games dictate we care about. We should - and now can - remember our companions for their stories. And never for the times they got stuck in a doorway.