How The Last Of Us raised the bar for video game narratives

An action game with real emotional weight

When I think back to 2013’s The Last of Us, it’s not the stealth segments that stick in my mind. It isn’t the gunplay, or the platforming, or even the blind, shambling Clickers determined to chomp on your neck. Like most fans, I remember the story—the touching, often harrowing moments protagonists Joel and Ellie share. I remember the silent looks, the tears, and the hopeless decisions they faced.

It was, and remains, a masterpiece of storytelling. It’s still both gripping and polished enough to blast through in a handful of sittings, as I did the first time I played it.

But how did Naughty Dog make its characters so believable? How did it make you want to push on despite the oppressive world? And how did it make you care so much about Joel and Ellie’s fate?

I replayed it to find out, and spoke to a pair of developers of other narrative-led games to hear their take.

Less is more

Naughty Dog establish the tone in the first fifteen minutes. It’s Joel’s birthday, and his daughter, Sarah, has saved up to buy him a watch. They sit on the sofa making jokes (Joel: “Where did you get the money for this?” Sarah: “I sell hardcore drugs.”) and this brief glimpse into their lives raises the stakes for the impending disaster.

A parasitic fungus has swept across the US, turning humans into aggressive, shambling monsters. You see it happen from Sarah’s perspective, first as she timidly searches for her father at home, and then as she rides in the back of Joel’s jeep, searching for an escape route.

As they reach the edge of town, a soldier tasked with containing the situation opens fire. Joel survives but Sarah, her face twisted in agony, dies in her father’s arms as he tries in vain to pressure her wound. It’s an emotional moment, and one I wasn’t prepared for when I first played it.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

It’s far more subtle than most death scenes, too. You don’t see Sarah as she passes away—the camera pans from Joel scrabbling to save her, to his brother, who is watching on, and then when it comes back to Sarah, she’s already dead. Naughty Dog shows similar restraint throughout, with long stretches of silence or off-screen action, leaving it up to your imagination to fill in the gaps.

Jon McKellan, creative director of Stories Untold developer NoCode, tells me Sarah’s death scene knocked him back, too. “It totally stuck with me,” he says.

“I’m a dad, and when you become a dad and see films and games that deal with children dying, it hits you a lot harder. It really took me by surprise, and set the tone for the entire game in a way that I wasn’t expecting.”

Plenty of games have dark plots in which you’re battling the odds with almost no chance of surviving, which can feel overwhelming, and put some players off. But The Last of Us keeps you hooked by offering hope. Ellie, who you soon meet, is a potential source of a cure for the infection, and it’s your job to protect her. “It’s like Children of Men, one of my favourite movies: it’s a really grim world that they’re in, but there’s a glimmer of hope, and that stops it feeling like all is lost,” McKellan says.

It's not about you

Still, The Last of Us is far from the only game that’s ever tasked you with finding a cure for an apocalyptic disease. So what sets it apart? Unlike in most games, you’re not focused on your own survival—it’s all about Ellie, which changes everything for McKellan.

He believes that the contrast between the grim world and Ellie’s innocence—she’s constantly making jokes, and shows no sign she understands how dire the situation is—makes you feel a duty to keep her alive. “She’s a companion with you for 99% of the game, and she’s quipping, and you build a relationship with her, so you’re being constantly reminded of the goal,” he says.

“Every time you interact with something you’ll get a comment from her, she’ll pick up a comic book and make an off-the-cuff comment, and it adds up to something deeper than I expected.”

He also thinks that by giving you vague objectives—more often “keep moving” than “find power supply and turn it on”—The Last of Us never makes promises it later fails to deliver on, and so you have more motivation to push on. He draws a contrast with Dead Space, which plays out as a series of tasks the player fails at.

“I love Dead Space, but as soon as someone gives you a mission, you know it’s not going to work,” he says. “In The Last of Us, you weren’t being given missions. It was vague in the minute-to-minute direction, and I think that’s a really good way of not teasing the player too much, and just letting them slowly get there themselves.”

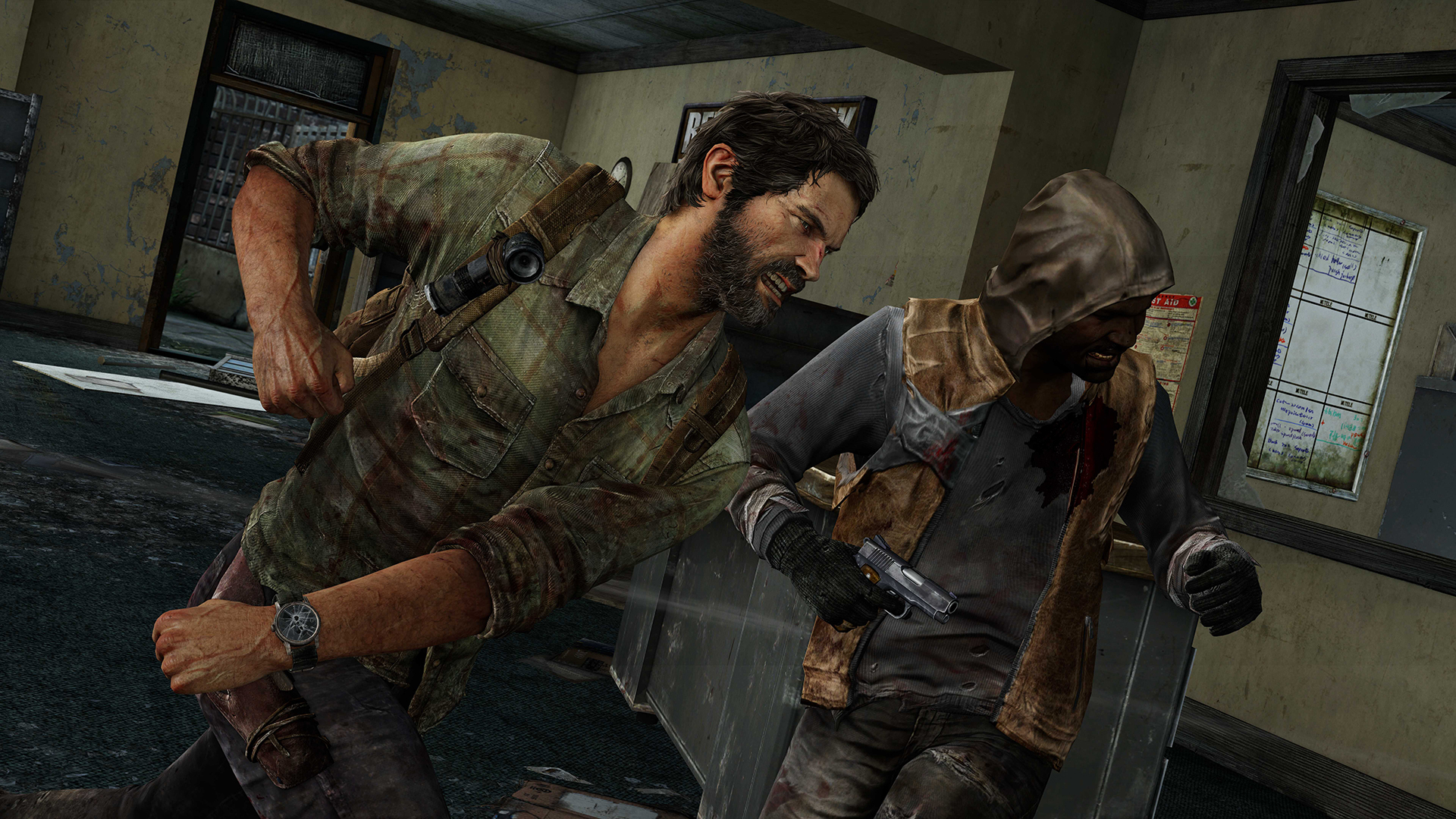

Naughty Dog needed players to care about the relationship between Joel and Ellie, and so the duo are always shown relying on each other. Joel is the protector, but Ellie saves his life more than once.

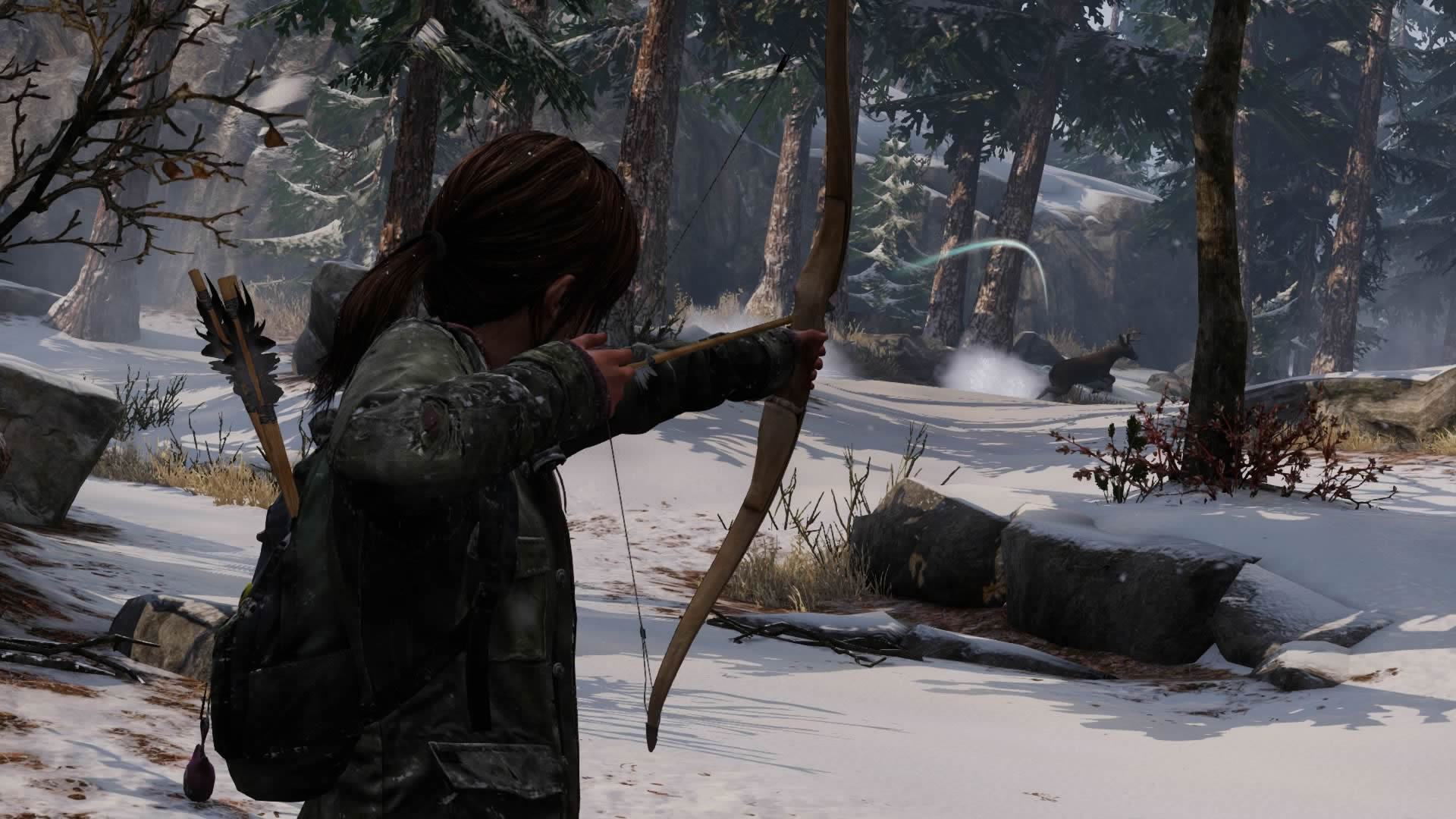

When Joel is near-fatally impaled by a metal rod, Ellie is forced to provide for them, hunting in the woods and fending off would-be raiders until Joel recovers. In other words, they can only survive as a pair, and when Ellie tries to run off at one point, it nearly ruins everything.

Nobody's perfect

Individually, Joel and Ellie are complicated, and flawed, which makes them more believable. Joel is particularly complex. Players might not like some of his choices—such as trying to palm Ellie off onto his brother later in the game—but the investment Naughty Dog makes in his internal struggles helps you empathise.

For example, when he tells Ellie, seemingly spitefully, “You’re not my daughter. And I sure as hell ain’t your dad”, you understand the subtext. He’s not just saying it to be mean—he’s battling with his own uneasiness at being given a second shot at fatherhood.

It’s not hard to imagine how torn he’s feeling: he wants to protect Ellie, but doesn’t want to replace his real daughter in any way. We only feel his pain because of what’s happened earlier, especially in the first 20 minutes.

The sequence when Joel is injured and Ellie goes hunting also shows just how tight a grip Naughty Dog has on the pace of the story. As soon as Joel is hurt we cut to a shot of a rabbit getting pierced by an arrow in the snowy woods. We don’t know what has happened to Joel, and the relatively mundane action lets the player’s mind wander and worry about his fate, building tension.

It puts me in mind of the section towards the end of Red Dead Redemption when John Marston returns to his ranch to carry out simple chores. The languid pace emphasises the action in the sequences sandwiching it.

But what’s a perfectly-paced story without a great ending? Joel ultimately abandons the whole mission in order to save Ellie, condemning mankind because of his own needs. Again, it’s a flawed decision, but one players understand. Greg Kasavin, creative director of Bastion and Pyre developer Supergiant Games, found it particularly memorable.

“The raw intensity and fury and selfishness and despair fuelling Joel’s decision to get Ellie out of the Firefly headquarters at the end made for such a spectacular climactic sequence,” he says.

“In the end, it was all about the people, and the Clickers and stuff no longer mattered. The final scene between Joel and Ellie is just such a great bit of writing, relying so much on body language and packing so much meaning into so few words.”

Tying it all together

It’s not just the ending either where the acting elevates the story. The motion capture tech was cutting-edge at the time, and even now, the characters feel like real people, with believable gestures and facial expressions.

The writing is purposeful and voice acting exemplary—but The Last of Us’s cast brings scenes together in ways few game casts can. “Its key scenes, such as its ending, relied on real acting between its principal characters to convey a depth of character that couldn’t come through in writing alone,” Kasavin says.

McKellan puts it down to the way the acting is captured in the first place. He likens the way some games capture voiceover to ‘radio adverts’, where actors turn up on the day and are given two hours to record all their lines.

“Clearly with the Last of Us, those scenes had been rehearsed and refined, and it wasn’t just good writing and dialogue, they’d developed a good scene,” he says. “The approach they took was way beyond what you’d normally get in a game.”

Going above and beyond is a clear theme for the development of The Last of Us. Individually, the writing, acting, character development, plot, pacing and tone are some of the best we’ve seen—and Naughty Dog had them all pulling in the same direction.

I don’t know if it can repeat the feat in The Last of Us Part II but, after replaying the first game five years later, I can’t wait to see them give it a go.

If you want to relive it, you don’t have to play through it all over again—you can just watch a movie made up of its cutscenes. Find that below, or take a look at the extended version with some story-relevant action sequences (I’d recommend it if you have the time).