How games create emotional connections

Whatever the genre, making an emotional connection is what most games strive for.

That doesn't necessarily mean that it wants to you fall in love with the hero, hate the villain or sympathise with Pac-Man's quest to eat the cherries – more simply that without some connection, a game is doomed to be a purely mechanical toy.

If you don't care… ultimately, you won't care. It's the difference between Doom being a three-dimensional shooting gallery containing basic AI constructs and a combination of hit-scan and moving projectile emitters whose co-ordinated interplay offers myriad spatial and reaction challenges, and Doom being that awesome game where you kick Hell's arse.

Emotion can stem from almost anything. A rocking tune that sets your heart on fire. The pretty girl at the end of your hero's quest. The self-satisfaction of beating a difficult challenge. Think of a boss in a game that particularly annoyed you – any will do. In that split second that its leering face appears in your mind, who gets the brunt of your hate: the boss itself, or the programmers and designers responsible for it.

Logically, we know that it's only a mix of animation, sound files and basic AI routines, but that doesn't matter. Sitting in front of Street Fighter IV, we just want to ram an ice-pick through Seth's heavily modified balls. Well. We do. Your experiences may vary. (But shouldn't.)

There's no real limit to what we can identify with. A drawing or well-written description can bring on sexual desire every bit as much as a photograph or video, just as our hate can be focused on anything from a wireframe triangle to a walking, talking Piers Morgan.

Some genres definitely put more emphasis on trying to make it happen, particularly the story-heavy ones – adventure and RPG in particular, although action games aren't far behind, and have many of the best examples.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

All of them have at least a few moments where they qualify, if only because frustration, boredom and despair are emotions every bit as much as love, guilt, rage and remorse. Let's take a closer look.

I, Protector

As we've mentioned many times, one of the biggest problems developers face is that the player is God. A game can't truly hurt us – not in a physical sense, at least. We can stop playing whenever we like, there are no personal ramifications to our actions, and if anything bad happens, we're just a quickload away from the status quo.

This tends to show up a lot in RPGs, with the hero routinely sent on missions like picking a fight with the town's toughest mobster or assassinating the king, then happily sauntering off into the sunset with no comeback at all. Sometimes, we don't even need the mission.

Mass Effect 2 demonstrates the sheer undiluted fun of giving every prick in the galaxy a taste of their own medicine. How do developers get past this? They think like supervillains, making us care about the other characters in the world, then getting to us through them.

Without any plot on its side, the arcade shooter Cannon Fodder did this by making Boot Hill into the level-select screen, with every soldier you lost turning into a cross on the rapidly grave-filled hill. The cunning X-COM series let you give a name to every member of your alien-hunting squad, knowing that most people would end up naming the characters after their friends and family and take extra care to keep Aunt Doreen away from the Chryssalids.

If instead they chose to give them bespoke appellations, the very fact that every soldier had a name, and had spent a whole career levelling up under your command made it a personal tragedy when one of your best troops finally took a bullet.

You might reload because you'd lost your primary gunner, but it was just as likely that you'd rewind time for Alan. Or, alternatively, put your least favourite squad members in the front-line, not give them any weapons and enjoy watching them get bisected by Sectoids.

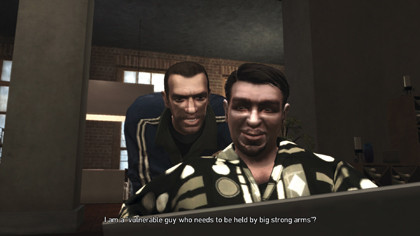

GTA: GTA IV tried forcing you to like its characters. It just built resentment, not closeness

Nobody said emotional connections have to be nice. One of the earliest games to understand the benefit of the protector role was the Infocom text adventure Planetfall way back in prehistoric 1983. Here you start out as a lowly starship mop-jockey, much like Roger Wilco of Space Quest fame, who survives the destruction of his spaceship only to crash-land on a planet in decaying orbit.

While there, you encounter a child-like and instantly lovable robot called Floyd who becomes your sidekick, and together you work to repair the planet's systems and find a way to escape. So far, so normal. And then you get to the puzzle where you have to send Floyd to his death.

This proved a turning point for many players, who refused to sacrifice him for their own gain. In practice, Floyd gets repaired at the end of the game and returns in the sequel, Stationfall, but nobody knew that at the time. This is probably the first time that a game managed to instil a reluctance to push on, and still one of the most famous examples, even for people who missed out on the whole genre.

I, hero

Many other games have made protection and rescue the core of their emotional journey, from blandly rescuing the main character's kidnapped girlfriend in damn near every 90s game ever, or failing at the task, as with Aeris' death in Final Fantasy VII.

In the Wing Commander games, losing one of your wingmen meant sitting through their funeral. In Mass Effect 2, the death of a likable character like Mordin or Tali in the suicide mission at the end of the game is all the worse for the fact that you could have prevented it, if only you'd been a little more careful.

The big moment might be a cut-scene, it might be interactive, it might be optional or part of the story, but it can work.

Ironically, the one place where this never seems to work is in that most hated of gameplay mechanics: the escort quest. These hateful, horrible missions always suffer from the same problem: they're a pain in the neck.

Any emotional connection you might have to the character is inevitably drowned out by annoyance at their slow pace, their insistence on trying to take on every enemy in the area no matter how slow, the enemies' tendency to rush them at every step, and above all else, your success being entirely based on their usually horrible AI. If none of that happens, it's usually because the AI character is either invincible or ridiculously overpowered, detracting from your own heroism.

Only Ico over on the PlayStation really stands out as an exception to the rule, with Half-Life 2 sitting exactly half-way. Alyx Vance can take care of herself. The other humans? Walking targets.