The giant telescopes that will change everything we know about the universe

From 'seeing' a black hole to solving the riddle of dark matter

Image credit: GMTO Corporation/Mason Media Inc.

Space telescopes like Hubble and Kepler might get all of the attention, but humanity's very biggest telescopes are all here on Earth.

Astronomy is essentially about studying light, and when it comes to giant telescopes, it's visually a case of bigger is better. Cue a whole new generation of awesome-sized observatories due to go online in the early 2020s.

The very finest telescopes are almost always built in the same places on our planet. Chile's dry Atacama desert is a favorite for telescope builders, largely because there are over 300 clear nights a year, and it's possible to build on freezing cold mountaintops at a whopping 10,000ft or higher.

That puts the telescopes high above the hottest, densest part of the Earth's atmosphere, thereby avoiding distortion.

Putting telescopes in the southern hemisphere also guarantees them the best view possible of the densest star fields of the Milky Way. In the northern hemisphere, the summit of Hawaii's Mauna Kea is a favorite, as is La Palma in the Canary Islands.

So why are more and more giant telescopes being built? The Hubble Space Telescope's successors, such as the (recently delayed) James Webb Space Telescope and TESS will make so many discoveries that an army of ground-based telescopes is going to be required to take a closer look.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Each will have a long to-do list, whether that be to detect dark matter, image a supermassive black hole or study exoplanets. Together, they will form a massive army of eyes on the sky that will change what we know about the universe and our place within it.

Event Horizon Telescope (EHT), worldwide

The Event Horizon Telescope was briefly the biggest telescope of all. The data is still being processed, but very soon astronomers will have something incredible; the first-ever image of a black hole (or two).

It's not an easy image to obtain. A black hole is where gravity is so intense that not even light can escape from inside it, so how can a telescope ever take a photograph of one?

The answer is radio astronomy, and no less than eight telescope arrays around the globe.

The EHT last year performed simultaneous observations of X-ray and gamma-ray bands at radio dishes in Chile, Spain, the US, Mexico, and at the South Pole.

Essentially they were linked to create an Earth-sized interferometer (a light measurer), with the hope of detecting the event horizons (a boundary beyond which nothing can escape) of two supermassive black holes: Sagittarius A* at the center of the Milky Way, and M87 in the center of the Virgo A galaxy.

If they're successful – an answer we'll know during 2018 – astronomers will finally have visual proof that Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity, which predicted the black hole's event horizon, was correct.

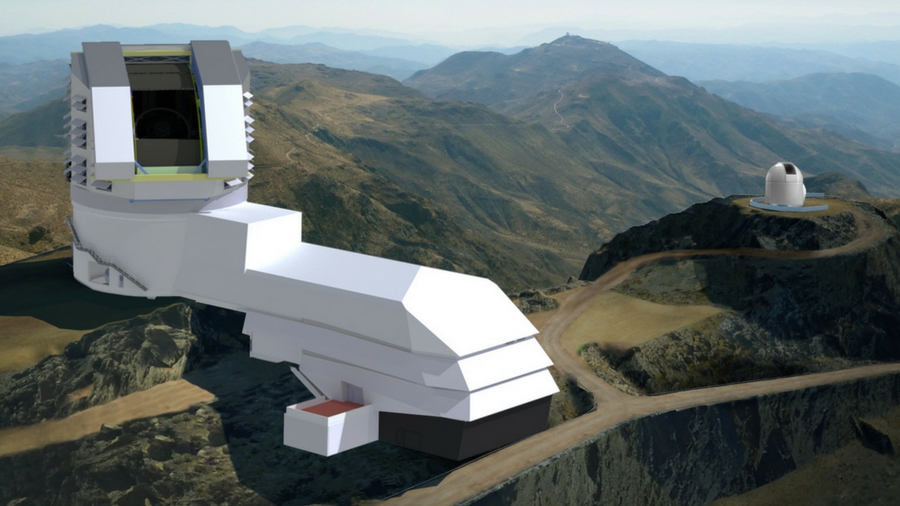

Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST), Chile

When a huge 20-metre near-Earth asteroid struck Chelyabinsk in 2013, there was a sudden realization that Earth is a sitting duck in space. Worse, no-one was even monitoring for incoming asteroids.

This is, thankfully, already changing, but by 2022 the LSST will be surveying the sky for potentially hazardous asteroids, and more.

An international project slated to last a decade, the LSST's 3,200-megapixel digital camera and 8.4m mirror will snap 800 photographs each night in six wavelengths, from ultraviolet to near infrared.

In what's being billed as 'the greatest movie ever made', each image will be 40 times the size of our Moon, with 15 terabytes of data being produced every night from 1,000 pairs of exposures. That's set to be the largest scientific dataset in the world, enabling astronomers to generate a highly detailed map of billions of galaxies, stars and objects in the solar system.

The LSST is being built at the Gemini South Observatory on Cerro Pachón in Chile's Elqui Valley, which will witness a rare two-minute total solar eclipse in 2019.

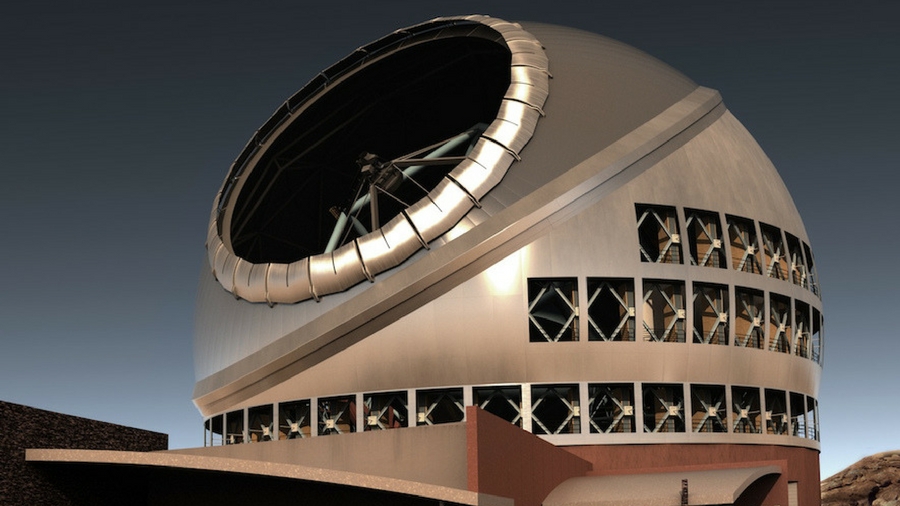

European Extremely Large Telescope (E-ELT), Chile

Can we take pictures of exoplanets? Up until now it's only been possible to find exoplanets from huge datasets that detect tiny changes in the brightness of starlight.

Cue the E-ELT, which will attempt to collect enough light and increase the resolution enough to take images of planets orbiting stars in the Milky Way. Its images will be 16 times more detailed than Hubble can manage.

It may be half a world away from its HQ near Munich, Germany, but the European Southern Observatory (ESO) is besotted with Chile.

Already it has ALMA and the VLT in the Atacama desert, and by 2024 this new flagship telescope, the US$1.2 billion E-ELT, will perch upon Cerro Armazones at a dizzying altitude of 3,046m/9,993 ft.

It's destined to be the world's biggest optical and infrared telescope thanks to a 39-meter primary mirror that will be formed by almost 800 hexagonal segments.

As well as studying exoplanets, the E-ELT will study the first galaxies and directly measure the acceleration rate of our expanding universe.

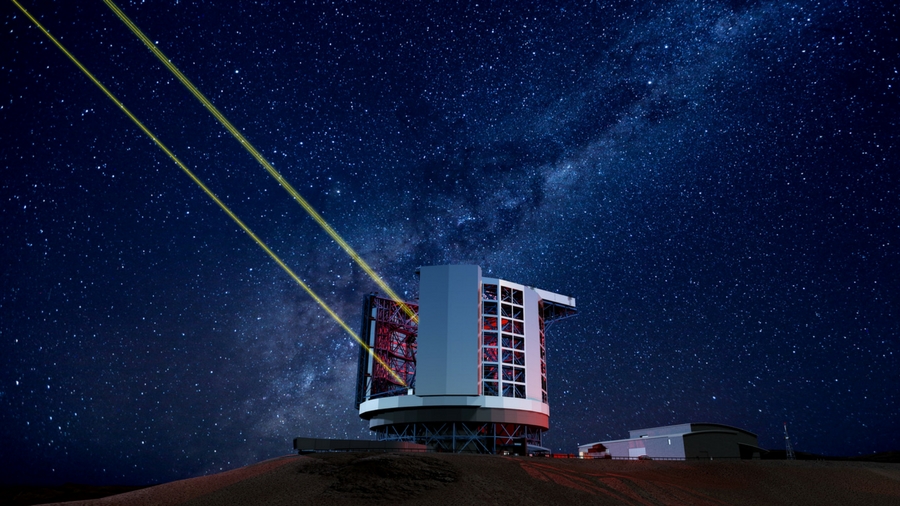

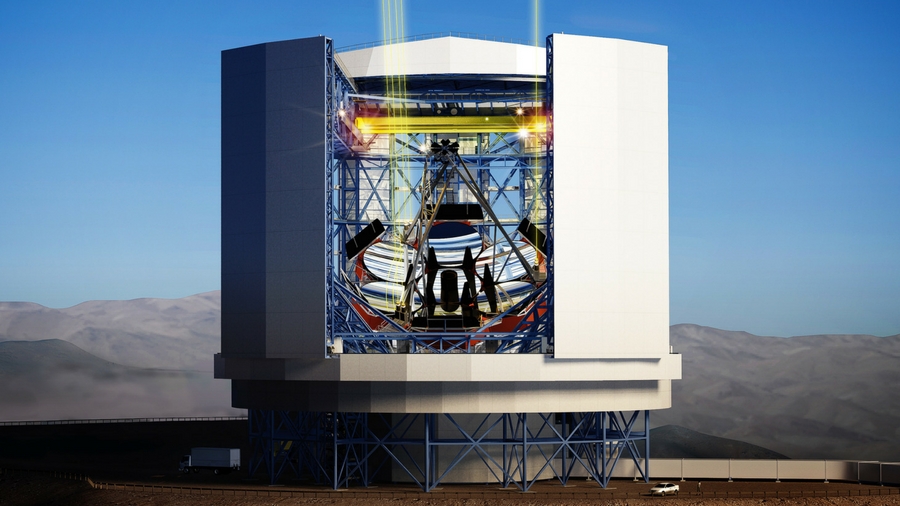

Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT), Chile

When it's completed in 2023, this US$700 million telescope will be the world’s largest optical, land-based telescope. Inside will be a whopping 24.5m mirror.

With new data on exoplanets from TESS, the GMT is likely to be used to probe their chemistry.

"As a planet passes in front of its star, a large telescope on the ground, like the GMT, can use spectra to search for the fingerprints of molecules in the planetary atmosphere," says Patrick McCarthy, Ph.D., Vice President for Operations and External Relations, GMTO.

Although it's being constructed at the Las Campanas Observatory in the Atacama Desert, and high above the thickest part of Earth's atmosphere at 2,550m / 8,500 ft., the GMT will also include a technology to correct for any heat distortion.

"As light from distant stars and planets pass through the Earth’s atmosphere, irregularities in the temperature and density of the air distort the image – just like hot air above highway pavement makes images shimmer," explains McCarthy.

Cue adaptive optics, a technique for removing that blur and restoring the full power of a telescope. "With adaptive optics we can image planets, and with images we can look for color variations due to weather and surface features."

The GMT's images will be 10 times more detailed than the Hubble Space Telescope.

Just a century ago astronomers thought the Milky Way was the entire universe. With these giant telescopes, we could be on the cusp of photographing distant planets, black holes, and monitoring what's happening around Earth in new stunning detail.

- Travel to far-out worlds with the best VR games

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),