When Hubble dies, we're going to learn even bigger secrets of the stars

$8.7 billion new space telescope is 100x times more powerful

It's revolutionised astrophysics and human understanding of the scale of the Universe, but the Hubble Space telescope's illustrious career since its launch in 1990 is almost at an end. Although NASA has no official de-commissioning date – Hubble is still returning 10TB of new data every year – it's never going to be able to peer into the edges of the Universe and photograph the dawn of time. First, it orbits Earth, so its view is blocked by the Sun for half the time. Second, what astronomers need is a space telescope that's built to detect the infra-red light that the first-born galaxies now emit.

That means a bigger, colder and more sensitive space telescope that orbits from much, much further away.

Despite nearly 13,000 science papers having been written using its data, Hubble's twenty-fifth anniversary is also doubling as its retirement party. With all upgrades in its past, its only visitor now will be a robot to push it towards Earth, where it will burn-up in the atmosphere.

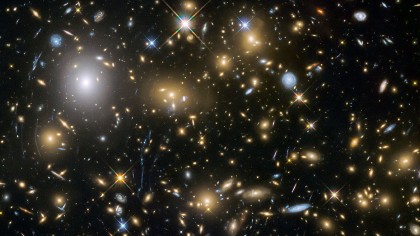

During the three billion miles it's travelled around Earth, the images it's taken have totally changed science and astronomy. So much so, in fact, that its own success has led to its imminent replacement. Although it's well capable of taking photographs in visible ultraviolet light, Hubble was the first space telescope to detect infrared light, and it's been in this infrared spectrum where its biggest discoveries have been made.

The red end

The further a galaxy is away from us, the longer the wavelength of the light that reaches us, which is the red end of the spectrum. This is called red-shift, which Hubble can handle, but isn't built exclusively for. The last Hubble Ultra Deep Field image of 2014 – taken in ultraviolet – showed galaxies between five and 10 billion light years away, though Hubble has also spotted galaxy EGS-zs8-1 a stunning 13.1 billion light years from Earth. To get any closer to the Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago/away, a new 'scope is needed that's built solely to detect infrared light.

Webb of intrigue

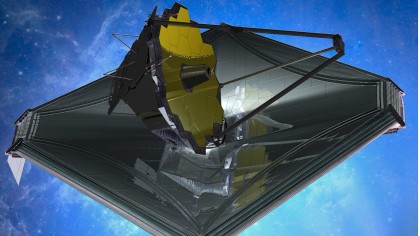

Cue the James Webb Space Telescope, which has cost US$8.7 billion to construct and will be 100 times more powerful than Hubble. The name may not sound as iconic (after all, Edwin Hubble was "the man who discovered the cosmos"), but Webb is named after James Webb, who ran NASA in the 1960s and is credited with making the Apollo Moon landings a reality.

Webb is no Johnny-come-lately. Just as Hubble was originally planned in the 1970s and launched seven years late, Webb's development began almost 20 years ago, when it was known as the Next Generation Space Telescope. It's a joint effort between NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Canadian Space Agency.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

How is Webb better than Hubble?

In terms of magnification, it's all in the mirror. At 2.7 times the diameter and with six times the area of Hubble's, mirror, Webb's mirror will gather a whole lot more light. Meanwhile, its infrared instruments will detect far longer wavelengths, so it will see those red-shifted galaxies more clearly.

Key to its infrared abilities is its distance from Earth at what's known as the Earth-Sun L2 Lagrange point. Out here, 1.5 million km from Earth, Webb will effectively orbit the Sun at the same speed as the Earth does, and reflect (and use, as solar power) the Sun's light and heat using a huge five-layered sunshield. That way, Webb can be cold enough in the shade to detect infrared light. Being at L2 also means it can observe the cosmos permanently.

But there's a potential problem. Unlike Hubble, which was famously fixed in 1993 after the "spherical aberration" problem, Webb is too far away to ever be fixed or upgraded. Webb must work perfectly first time.

What will Webb do?

Webb only has a ten-year mission, though the chances of it working beyond 2020 are pretty high. In that decade it has four missions; The End of the Dark Ages: First Light & Reionization, The Assembly of Galaxies, The Birth of Stars & Protoplanetary Systems, and Planetary Systems & the Origins of Life.

Although it's built to study the "dark ages" after the Big Bang – and the first stars and galaxies – Webb will also help in the discovery of exoplanets around distant stars, something that astronomers will hugely benefit from. "I am very excited about the capability to characterise exoplanets and planet forming environments, both through direct imaging and spectroscopic studies," says Dr. Nick Moskovitz, at astronomer at Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona.

"There is also interesting work to be done looking at the compositions of small bodies throughout the Solar System, from near-Earth asteroids out to the Kuiper Belt." The Webb will also be well suited to studying the physical properties of asteroid and comets.

When will Webb launch?

Webb is scheduled to launch on the back of an Ariane V rocket from the Guiana Space Centre in French Guiana in October 2018. However, it won't get to its orbital point for three months, during which time scientists back in Maryland, USA will begin to position its mirrors and focus its optics by taking test shots. Even when it reaches L2, it will take another three months to optimise the optics before science can truly begin.

Able to probe even farther beyond the spectrum of light than its predecessor can detect, Webb will uncover more about the nature of reality and see to the very edge of the Universe. If you thought Hubble was good, you've seen nothing yet.

- Everything we've ever learned about Pluto...so far

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),