Ubuntu 11.04 explored: a new dawn for Linux?

Groundbreaking release heralds the rise of the Unity desktop

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Ubuntu releases are always eagerly awaited, generating feverish debate on the blogosphere, but Ubuntu 11.04 Natty Narwhal has received an unprecedented amount of attention because it's different - in more than one sense of the word.

This release is about the one area that's often overlooked in the Linux ecosphere, the desktop. Linux has struggled with the desktop; compositing window managers such as Compiz Fusion allowed you to play around with it but it still looked the same.

But if you think the Gnome 3 Shell is different, wait till you experience Unity - and there's a lot more to it than glitter.

In this article we'll explore the desktop in close detail, tell you how to use it productively and compare this release with previous versions and its major competitors. In adopting the Unity interface, Ubuntu 11.04 marks a major departure from Gnome for Canonical.

There has been no love lost between it and members of the Gnome Foundation and, indeed, between Canonical and the developers of music player Banshee. At the end of it all, though, Linux users have two new desktops that are a radical departure from the Gnome desktop of old. And, if everything goes to plan, the separation could in fact herald a new era of collaboration between Linux communities.

What's new in Natty?

The biggest addition to Natty Narwhal is its new interface which requires accelerated graphics. Although you don't have to have an OpenGL graphics card to use Natty, you do need one to experience the full Unity 3D desktop - on machines that lack the minimal graphics processing requirements of Unity, there is a fallback 2D Unity mode.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

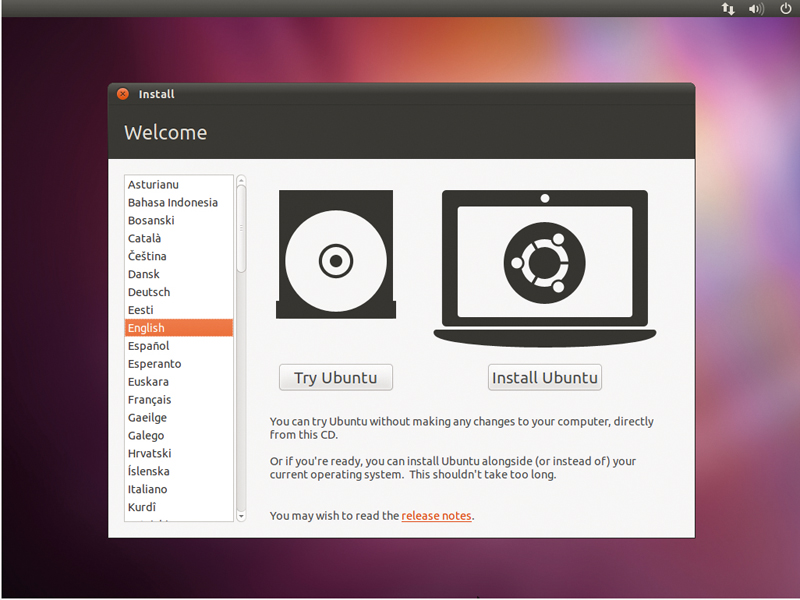

Installation is a piece of cake. You can use the Live Desktop CD or, if you haven't installed it before, you can use the Windows-based Ubuntu Installer (WUBI) to install and run it from within a virtual disk within Windows. To install Ubuntu onto its own partition, boot from the Desktop CD.

The most important decision during installation is while preparing your hard disk for Ubuntu. The installer makes your job easier by detecting operating systems or other distros already installed on your disk. You can go with the default option to install Natty alongside your existing OS.

The installer will automatically carve out space from the existing OS to create a new partition and it'll also give you the option to optionally adjust the size of the partition graphically. The next partitioning option will wipe your disk clean and give all the space to Natty. The last option allows you to create, remove and resize partitions manually. Use either of these two only if you know what you are doing.

Besides the Desktop CD, there's also the Alternate Install CD which has a text-based installer. You can also use that CD to upgrade existing Ubuntu installations.

Behind the scenes, Ubuntu ships with the latest stable Linux kernel v2.6.38. It boasts of improvements to the Btrfs, and EXT4 file systems, and the usual dose of updates to existing drivers and a host of new ones. There are also updates to the GCC toolchain, dpkg, and Natty now includes the latest version of Upstart to replace the traditional init daemon, that can also activate D-Bus services.

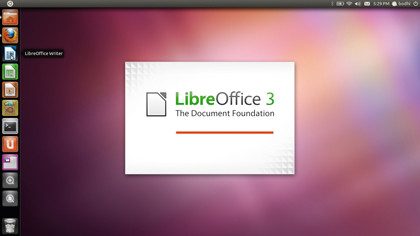

Onto the more visible changes then. A fresh Ubuntu Natty install has the latest LibreOffice 3.3.2 office suite, Firefox 4.0 web browser, the Shotwell photo manager, Evolution for your mail, address book, and calendaring needs, the Gwibber microblogging client, Empathy for instant messaging, and the usual assortment of Gnome tools and utilities.

The Banshee music player has replaced Rhythmbox, and lets you buy music from within the player itself, either via Amazon or Ubuntu One's music store.

Natty's software selection is comparable to other mainstream distros such as OpenSUSE and Fedora. All have now dropped OpenOffice.org in favour of LibreOffice and moved to the latest release of Firefox. Fedora, like Ubuntu, had replaced the F-Spot image organiser with Shotwell a couple of releases ago, but F-Spot remains the default on OpenSUSE.

To compliment the Unity desktop session, the X.org server bundled with Natty includes support for multitouch devices via the XInput library. There have also been improvements to home-brewed software such as Ubuntu One.

The very popular Ubuntu Software Centre now allows you to rate and review apps and then share your opinions on the social networks you have configured with Gwibber.

The Unity desktop

Love it or hate it, Ubuntu's Unity desktop is different and undoubtedly a refreshing change from the desktops of old. But there is a lot more to the desktop in Natty Narwhal than Unity.

Several teams focusing on improving the user experience collaberated on the desktop. One of them, the Ayatana project - first announced by Mark Shuttleworth in 2009 - dealt with several aspects that present information to the user, such as notifications, indicators and the launcher.

Another important aspect of Natty's desktop is that it is designed for touch interfaces. The distro ships with several multitouch and gesture recognition libraries that let you ditch the mouse. This bonds well with the Linux kernel that comes with Natty because it includes drivers for several touchscreens, such as the Cando version on our Acer laptop.

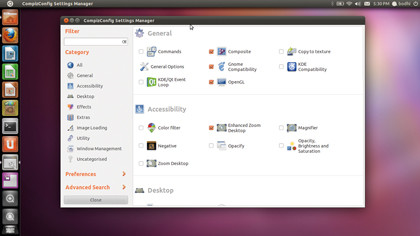

Another major shift is Unity's move away from Metacity, the old Gnome Window Manager, to the compositing window manager, Compiz. The move comes at a price though. To fully experience the Unity desktop you need a graphics card that supports OpenGL 1.4 or newer. Before you shake your head in disapproval, though, remember that that version of OpenGL was released way back in 2002. In tests done by Ubuntu, Unity will run on GPUs made by either Nvidia or AMD over the past five years.

Well integrated

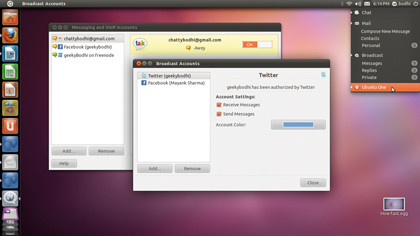

Lots of work has been done integrating the various Gnome apps with the Ubuntu desktop. Previous Ubuntu releases had glimpses of this work, most notably the MeMenu, which allows you to broadcast to social networks such as Facebook, Twitter, and Identi.ca, and set the status for instant messaging on your IM accounts.

The MeMenu integrates the Empathy instant messaging client and the Gwibber microblogging client and you can also set up these accounts through it.

Then there's the Messaging menu which has a section for all messaging accounts that you have configured under Ubuntu. Along with all the social networking accounts in the MeMenu, this also includes mail which is handled by Evolution. You can set up the mail account from within the Messaging menu itself, which also sets up Ubuntu's file sharing service Ubuntu One.

The Messaging menu keeps count of the number of unread or new messages for every account it is tracking. The integration of apps in the panel expands beyond the two menus for messaging. The Banshee music player is fused in the Volume indicator. It displays the currently playing track, along with its cover art, and gives you basic controls to pause, and change tracks.

Besides this, you'll find the network manager rolled into the network indicator, Evolution's calendar module in the clock, and the one stop for setting up the system in the PowerOff menu.

Working in Unity

The whole design philosophy behind the Unity desktop is to make it intuitive. This works pretty well for new users but for users familiar with the Classic Gnome desktop, Unity might come as a bit of a shock.

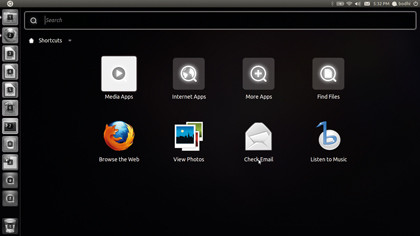

Besides the notification area which houses the indicators and the MeMenu, there's the launcher that gives you quick access to some of the installed apps. Then there's the dash which is activated by clicking the Ubuntu logo at the top left of the screen. When the dash is activated, the icons in the launcher turn monochrome, and the icons in the dash 'lens' are shown in colour.

A lens is a graphical interface for a particular task. For example, as well as the Global Search lens that you get when you click the Ubuntu icon in the top left of the screen, there is an Application lens in the launcher which shows the available apps, most frequently used apps, and apps that can be downloaded.

The Unity interface is designed to give apps maximum real estate on the screen. One of the ways it does so is by using Mac OS X-style Global menus. When you run an app, menus for that app are displayed in Unity's top panel.

All running apps on all virtual desktops are represented with an icon in the launcher. The launcher is animated and "squishes" icons when there are lots of apps. When you hover over it, the launcher scrolls through the icons of all the running apps.

Right-click on an app's icon to display its unique Quick List options which are actions you can perform without switching to the application. For example, Firefox gives you the option to open a new window, and the Gnome Screenshot utility gives you the option to take screenshots.

2D vs 3D

So why is Canonical investing in two similar looking desktops, rather than concentrating on the one that runs on most hardware? In a blog post, Bill Filler, engineering manager at Canonical USA, explains that although the two versions offer roughly the same functionality, the 3D version harnesses the full power of OpenGL for a richer set of visual effects and tighter integration with the Compiz window manager.

Many were surprised that Ubuntu went with Qt when they had experience with Enlightenment Foundation Libraries (EFL) which they had used to create a 2D launcher for Ubuntu Netbook Edition 10.04. Again, Filler explains that Qt was a better fit for Unity 2D due to its active development community, wide range of excellent development tools, such as Qt Quick and Qt Creator, great documentation, and support options.

Unity 2D is available in the Natty mirrors, and can be installed via the Software Centre. Once installed it'll show up in the list of sessions at the login screen. If Unity 2D is installed, and your machine can't run the full blown Unity, it'll fall back to Unity 2D. Otherwise, the fallback will be the classic Gnome with the gnome-panel.

With almost two decades of writing and reporting on Linux, Mayank Sharma would like everyone to think he’s TechRadar Pro’s expert on the topic. Of course, he’s just as interested in other computing topics, particularly cybersecurity, cloud, containers, and coding.