Should we go to Venus instead of Mars?

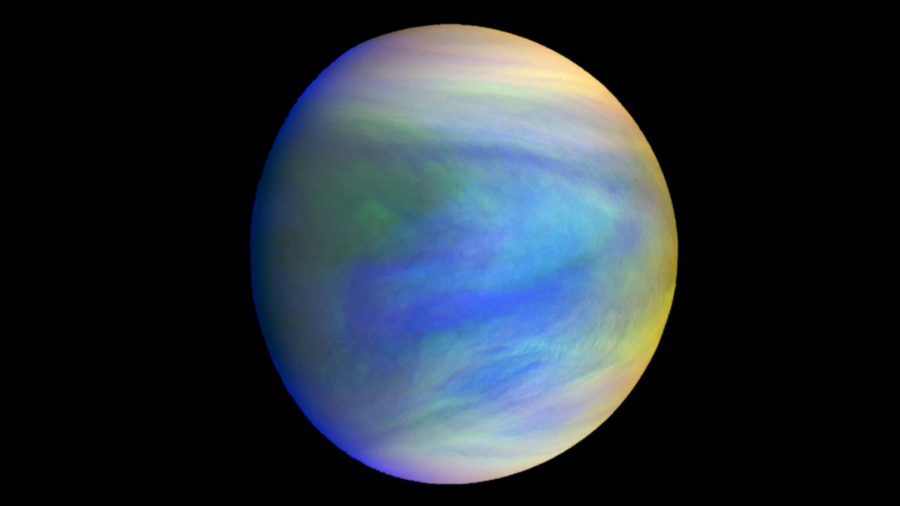

Astrobiologists think there could be life in the sulfuric acid clouds above 'Earth's twin'

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

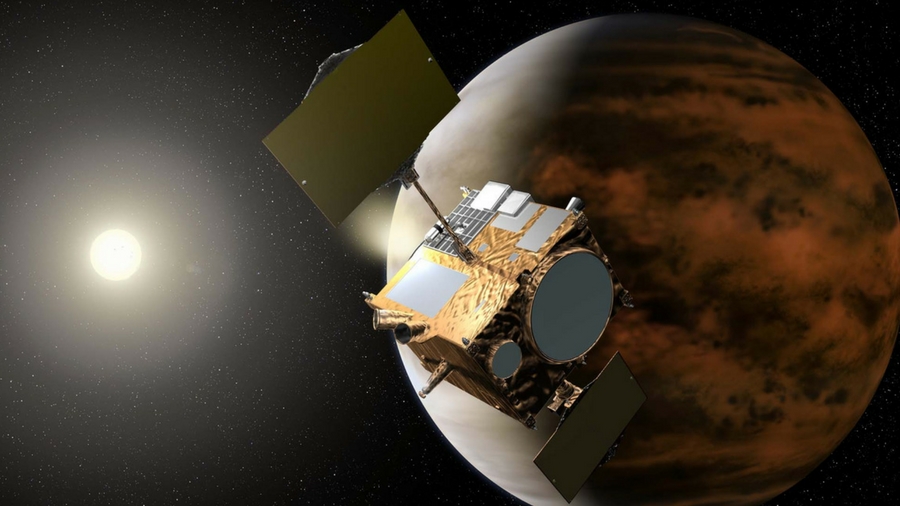

Image credit: Institute of Space and Astronautical Science/JAXA

Why always Mars?

The hot topic in planetary exploration is when and how we’ll put humans on Mars. NASA obsesses over it, so does Buzz Aldrin, and even Elon Musk is aiming for the Red Planet with his red Tesla Roadster.

There's also a growing obsession with a couple of moons, Europa around Jupiter and Enceladus at Saturn.

So, amid all the interstellar talk, here's another question: why not Venus?

Yes, it's much hotter (enough to melt metal), its surface gets regularly doused in sulfuric acid rain, and no robotic rover has ever managed to survive on the planet for over 127 minutes.

However, some think the clouds above Venus are just as likely to host basic lifeforms as anywhere else in the solar system.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Could there be life in the clouds of Venus?

In a paper called Venus' Spectral Signatures and the Potential for Life in the Clouds published in March 2018 in the journal Astrobiology, researchers claim that the planet's clouds 47.5–50.5 km up could host life.

"The lower cloud layer of Venus is an exceptional target for exploration due to the favorable conditions for microbial life," it reads, the authors also pointing out the environment's moderate temperatures and pressures, but also how little we know about the atmosphere of Venus.

"Acid-resistant terrestrial bacteria could potentially tolerate the Venus' cloud environment," they add.

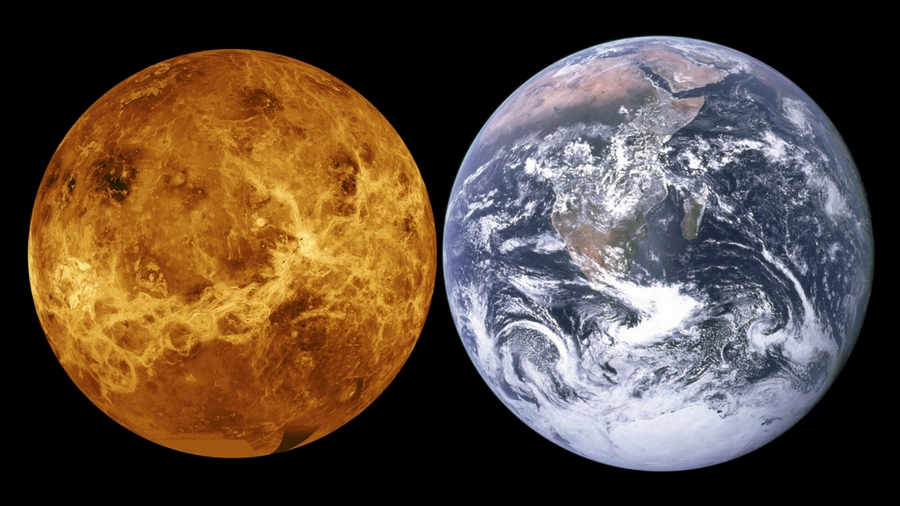

Also contributing to the evidence is that Venus had a habitable climate for at least 750 million years, with liquid water on its surface for two billion years.

"This suggests a geological time frame that is sufficient for life to have evolved in Venus' environment, especially when the time estimates required for the evolution of life on Earth are considered," reads the paper.

"As conditions on Venus' surface warmed and became increasingly inhospitable, life could have migrated to the clouds as the surface water evaporated." So, why don't we take a look?

When was the last mission to Venus?

Venus has been pretty much ignored by NASA since its Magellan mission in the 1990s that mapped its surface.

Meanwhile, the European Space Agency's Venus Express orbited the planet from 2006-2014, and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency's (JAXA) Akatsuki satellite has been studying Venusian weather from orbit since 2015.

Are there any planned missions to Venus?

The likes of NASA and Russia’s Roscosmos are always thinking about it, but Venus missions often lose out to competing missions to Mars or more distant moons. However, there are several exciting proposals.

The cloud-taster

'Air vehicles' or 'atmospheric rovers' that float in the upper atmosphere are what's needed to confirm whether there is indeed microbial life up in the clouds.

The semi-buoyant and solar-powered Venus Aerial Mobil Platform (VAMP) would 'float down toward the planet almost like a falling leaf' from an orbiter, and spend a year sampling the clouds, even using a microscope to identify living microorganisms.

It's been suggested that VAMP could form NASA's contribution to the Venera-D mission to Venus proposed by Roscosmos. Destined to include an orbiter and a lander, it's likely to launch in the late 2020s.

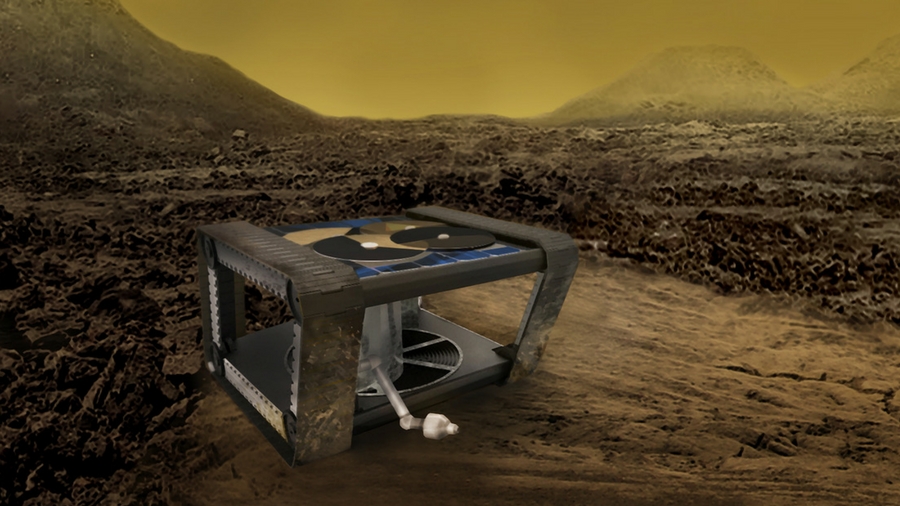

The clockwork rover

The first problem any surface-landing robot is having its electrical systems melt (the most successful lander, the Soviet-era Venera 13 probe, survived for a mere 127 minutes back in 1982).

However, NASA has plans for a 'clockwork' rover called the Automaton Rover for Extreme Environments (AREE) that will swap-out electronics with a mechanical computer and logic system.

It's all a bit 'steampunk'; with data communications impossible, AREE could inscribe phonograph style records with data, then launch them on a balloon to a high altitude drone, which would then relay the data data back to Earth. How quaint.

It proposes measuring atmospheric composition on the way down, then drilling into the surface of Venus to retrieve soil samples for analyzing itself using X-ray. However, VICI would have to act fast; the design would survive for only a few hours once on the surface.

Though overlooked by NASA late last year, the space agency then put more funds into developing the Venus In situ Composition Investigations (VICI) mission concept.

To help this twin-lander mission get round the the extreme heat and pressure problem on the surface of Venus, the plan is to use lasers to measure the chemistry, minerals and composition of rocks in Venus' highlands, the planet's geologically oldest area.

Crucially, the two VICI rovers would measure atmospheric composition and structure during their descent.

The surface-scraper

Another idea from NASA that has, for now, lost out to other missions is the Venus In Situ Atmospheric and Geochemical Explorer (VISAGE).

It proposes measuring atmospheric composition on the way down, then drilling into the surface of Venus to retrieve soil samples for analysing itself using X-ray. However, VICI would have to act fast; the design would survive for only a few hours once on the surface.

A manned mission to Venus?

It's possible, but not if you're talking about landing on the surface.

Venus at some point became plagued by a greenhouse effect gone mad, and now suffers a surface temperature of 873 °F/467 °C.

Cue a few plans to live in a 'cloud city'

That makes sending humans to the surface impossible.

However, unlike Mars' thin and useless atmosphere, Venus' thick atmosphere protects against radiation. Cue a few plans to live in a 'cloud city'.

Causing HAVOC on Venus

The clouds of Venus have long been talked-up as a place worth sending balloons and a crewed mission.

NASA's High Altitude Venus Operational Concept (HAVOC) from 2015 is a concept for a piloted, helium-filled airship consisting of three phases.

Initially, NASA would send a small robotic airship to test the technology for a crewed mission.

If successful, NASA would then construct a bigger inflatable airship, and send an unmanned Venus Ascent Vehicle spacecraft to orbit Venus in readiness for the crew's return to Earth.

The final phase would be to send a crew in a capsule that would descend by parachute, unfurl an inflatable airship, and have the crew live in it for a month, before returning home.

Consistently overlooked by space agencies despite being the closest planet to Earth – both geographically and geologically – some might think that visiting a hellishly hot planet with raging global warming issues sounds like a crazy idea.

Others think that Venus could show us exactly what we need to know; Venus could be Earth’s future self.

- The giant telescopes that will change everything we know about the universe

- The best VR headsets let you travel to distant worlds without ever leaving your living room

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),