So long, Cassini: how NASA's doomed space probe changed everything we know about Saturn

Its stunning 20-year career comes to a flaming end

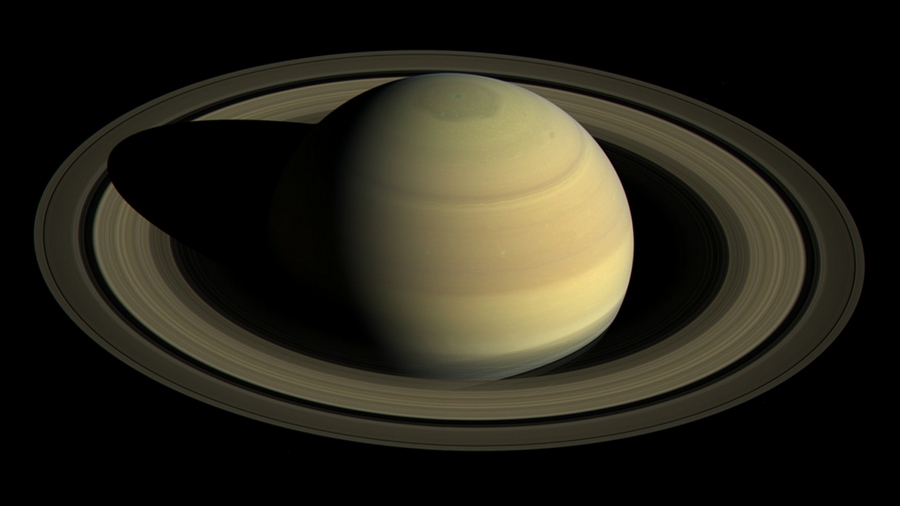

On 15 September, one of NASA's greatest space probes will destroy itself. After thirteen fruitful years studying Saturn, its stunning rings and many of its 62 strange moons, the Cassini space probe is being steered towards the giant planet itself. The first probe to spend any kind of time at Saturn, Cassini – a joint effort of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency (hence it being named after an Italian astronomer) – has long outlived its planned four-year mission.

Launched in 1997, it's made maximum use of its two onboard cameras to send back over 450,000 incredible photographs, while its instruments have transmitted troves of data. What started as a four-year mission eventually became a whole new mission – the Cassini Solstice Mission – and what it achieved is astounding.

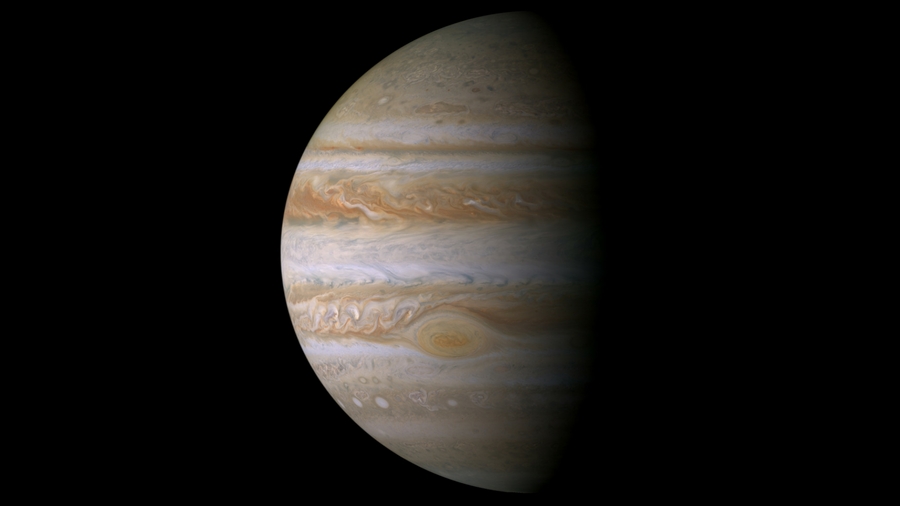

A definitive Jupiter

Wrong planet? When you see an image of Jupiter, you're most likely looking at one of Cassini's true colour mosaic images taken during the probe's flyby in December 2000 on its way to Saturn. This image is comprised of 27 separate photos; nine segments each imaged in red, green, and blue to create true color.

However, during Cassini's death throes a new space probe, Juno , has begun orbiting Jupiter and is already producing the kind of images a flyby just can't get. Onwards to Saturn…

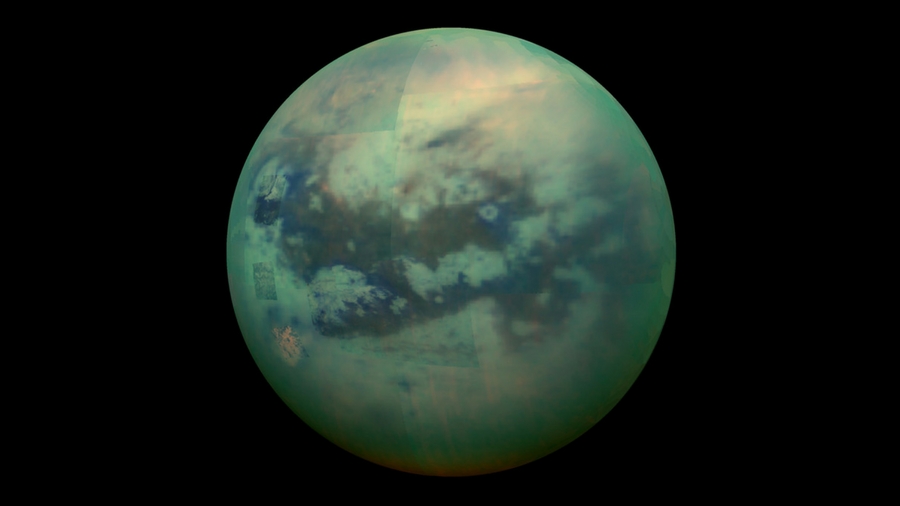

Unveiling Titan

It's Christmas Day 2004, and after just six months at Saturn, Cassini has a gift for its new host planet. The gift is called Huygens, a tiny space probe, which Cassini sends towards Titan , the only moon in the solar system with an atmosphere. What it finds a few weeks later is incredible, as seen on the below time-lapse; drainage channels, a frozen floodplain, and icy cobblestones. Titan, it seems, has liquid on its surface. Humanity's only lander in the outer solar system will live long in the memory – and it made some awesome music, too.

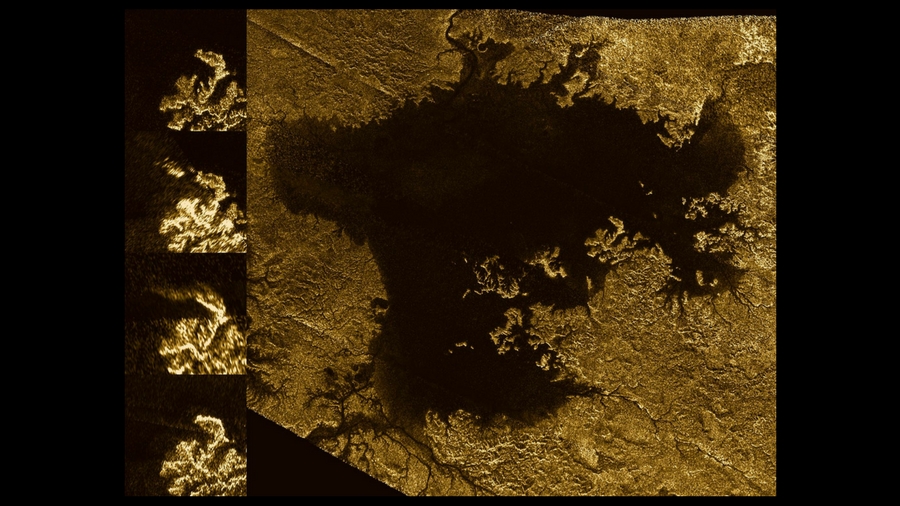

Titan's 'magic island'

In its 13 years Cassini has conducted flybys of moons no less than 162 times, but none have proved so fascinating – and un-moon like – as Titan, which Cassini conducted its 127th flyby past last April. Earth-like? It has mountains, dunes, rain and weather, but it's so cold that ice is as rock, and ethane and methane are chilled to form liquid lakes, rivers and oceans. Radar images from Cassini show a strange 'magic island' that changes over time. Waves? Bubbles? No one is quite sure, but there's something reflecting down there … and plenty to ensure that further exploration of Titan will remain high on planetary scientists' to-do list.

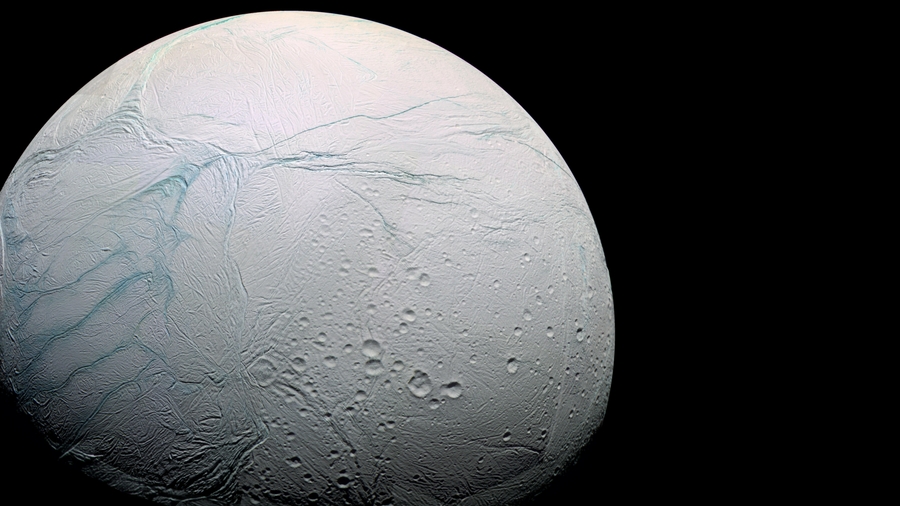

Exploring Enceladus

If life does exist elsewhere in the solar system, Saturn's moon Enceladus is now a candidate, thanks to Cassini. It first revealed that its geologically active moon has a global ocean of warm liquid water about 11-14 miles below an icy crust. However, it then discovered that the south polar region is much warmer, and the ocean there lies only two miles beneath the surface.

Cassini even photographed 'tiger stripe' fractures in this region that spew icy jets. "What is the warm underground ocean really like and could life have evolved there?" said Linda Spilker, Cassini Project Scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. "These questions remain to be answered by future missions to this ocean world." Cue the mooted Enceladus Life Finder (ELF) mission.

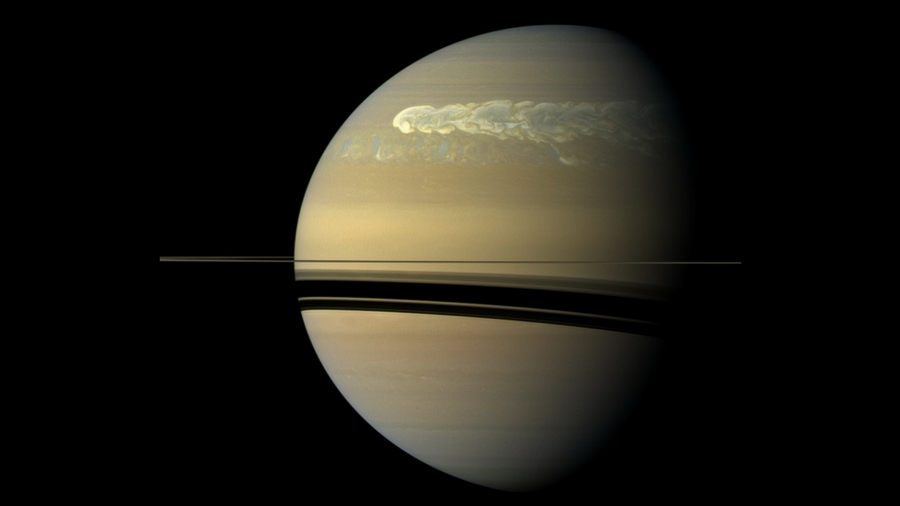

Saturn's 30-year superstorm

Jupiter's Great Red Spot has nothing on Saturn's storms. One of Cassini's biggest achievements has been to reveal the planet's volatility. First glimpsed in 2010, a giant turbulent storm was observed at 30 degrees north latitude as big as 190,000 miles wide, the largest, hottest stratospheric vortex ever detected in the solar system.

Infra-red measurements even discovered that the storm churns-up water ice from the atmosphere. Water ice hadn't even been detected at Saturn before.

Such storms at Saturn appear about once every 30 years, disrupting the three-tier cloud system at Saturn; water clouds, ammonia hydrosulfide clouds and ammonia clouds near the top.

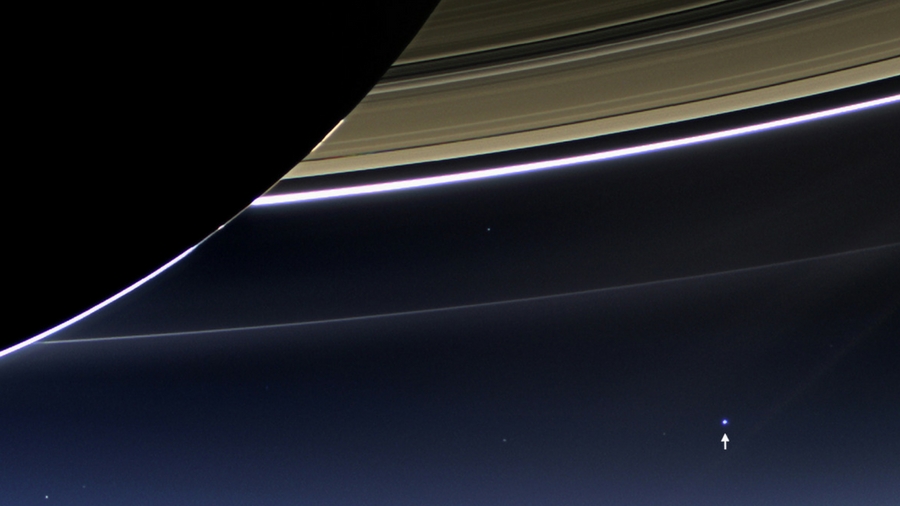

The Day the Earth Smiled

Did you smile at Saturn? Back in July 19, 2013, with the probe pointed towards Earth, 898 million miles away, while in orbit of the giant planet, Cassini took a very special wide-angle image spanning 404,880 miles. Above is only part of the 141 image composite; a bigger view of the entire planet also included Mars, Venus and several moons. It was the brainchild of Cassini scientist, Carolyn Porco, who described it as a chance to "celebrate life on the Pale Blue Dot" – and a clear tribute to Carl Sagan's legendary image taken by Voyager 1 in 1990.

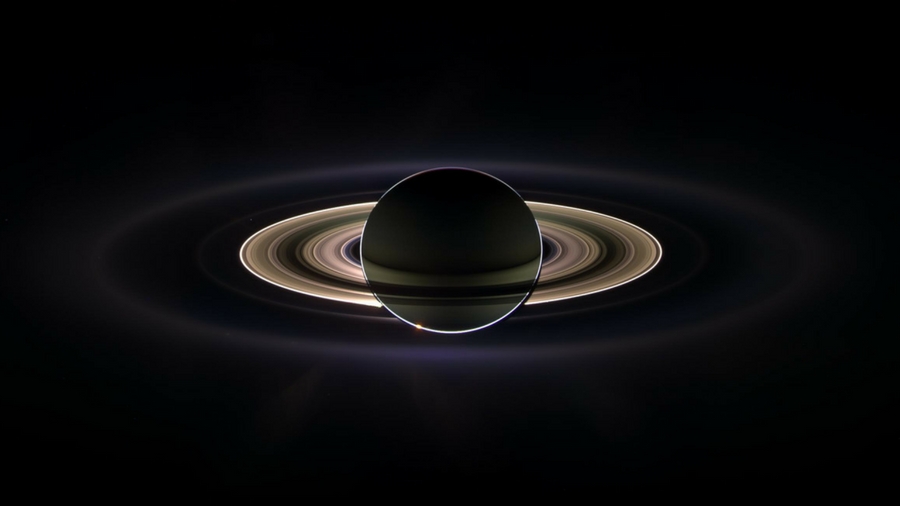

Saturn's faint rings

It's famed for its rings, so it was only right that Cassini delved a little deeper into them. It's doing that right now as it gets its closest-ever look as it nears the end of its mission, but perhaps the most revealing view so far has been this image. Taken in 2006, it shows faint rings exposed by Saturn's blocking of the Sun.

A combination of ultraviolet, infrared and clear filter images taken over 12 hours from within Saturn's shadow, Cassini detected two new faint rings that coincide with the close moons Janus and Epimetheus, and another with Pallene's orbit. The icy plumes of Enceladus supply the particles for its outer E ring.

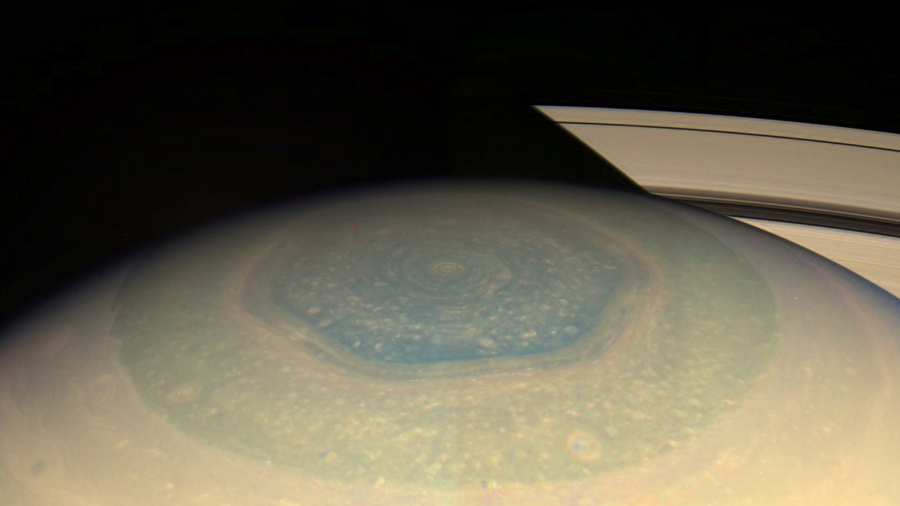

The Hexagon

First discovered by Voyager 2 in 1981, Cassini spent some time taking images of Saturn's hexagon, a bizarre and persisting five-sided cloud pattern – a current of air – around its north pole. A bit like a hurricane on Earth but lasting for at least 35 years, possibly much longer.

Cassini had to wait until the January 2009 equinox to get a look at the Hexagon in sunlight, then photographing it first as blue in 2012, then as golden last year as Saturn neared its summer solstice.

Saturn's seasons

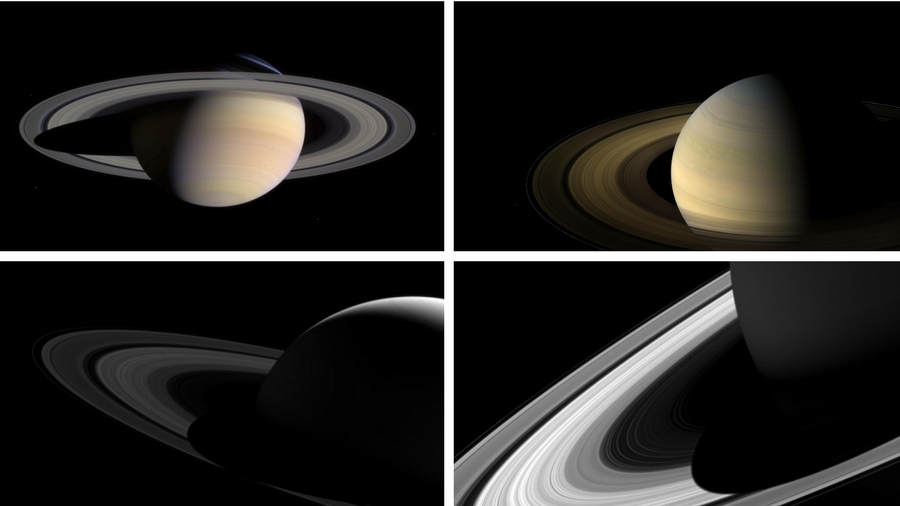

As with the Hexagon's changes over time, it's only the massive amount of time Cassini has spent at Saturn that has given us data on seasonal changes scientists would otherwise have been oblivious to. The same goes for views of Saturn itself. Since Saturn is tilted 27 degrees in its orbit of the Sun, Cassini was able to observe its shadow lengthening on its rings from 2004 until equinox in August 2009 (top left image), then shorten until northern solstice in May 2017. That solstice only occurs every 15 Earth years.

The final image?

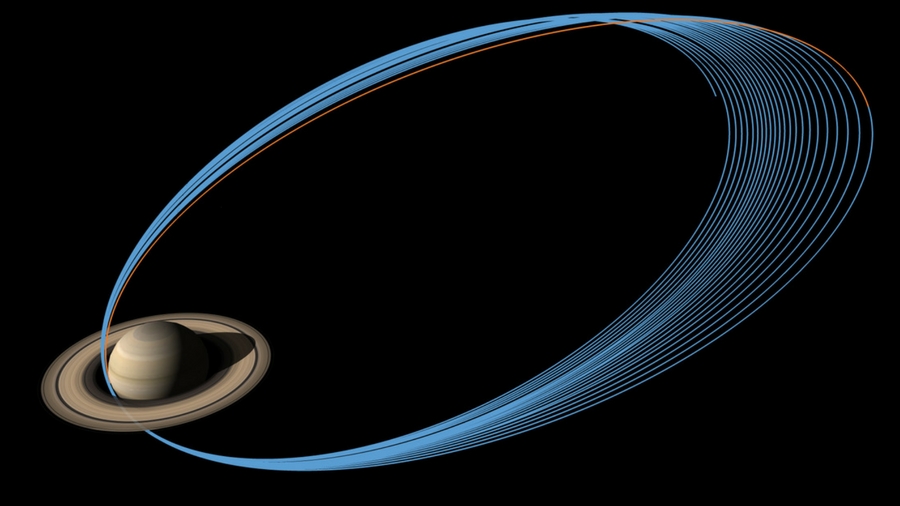

Its manoeuvring propellant spent, the 'grand finale' phase of Cassini's long mission has already begun; the last of its 22 super-close orbits between Saturn's rings will end on 15 September when it spectacularly burns-up in the planet's upper atmosphere (principally to prevent it crashing into a moon and spoiling it for future exploration).

"The Cassini mission has been packed full of scientific firsts, and our unique planetary revelations will continue to the very end of the mission as Cassini becomes Saturn’s first planetary probe, sampling Saturn's atmosphere up until the last second," said Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. "We'll be sending data in near real time as we rush headlong into the atmosphere – it's truly a first-of-its-kind event at Saturn." So long, Cassini.

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful