How 21-year-old data revealed the possibility of life on one of Jupiter's icy moons

This is why you never throw away old memory sticks

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

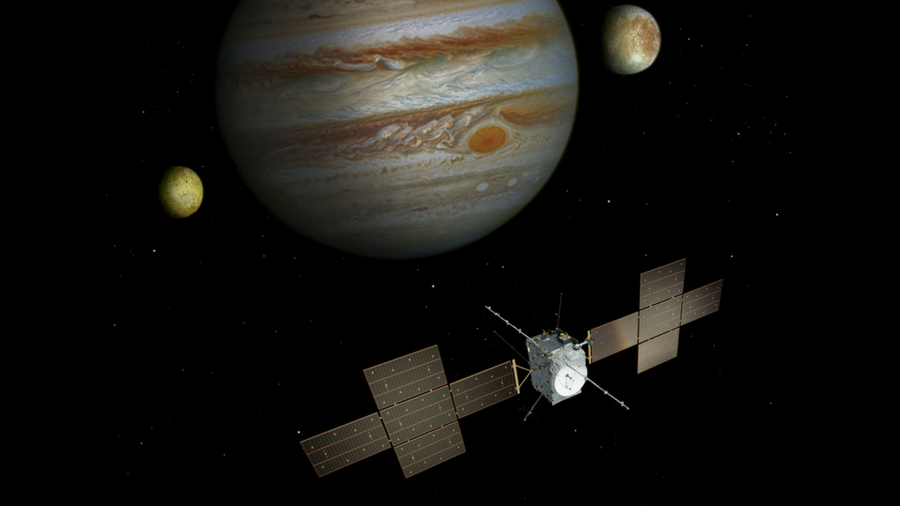

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Could we go fishing on a planet-sized frozen moon near Jupiter?

Using cutting-edge 3D modeling techniques unheard of last century, NASA scientists have re-examined 21-year-old data of Europa, one of Jupiter’s moons known to have a huge, salty, liquid ocean underneath its icy surface.

They found new evidence to back-up astronomers’ suspicions that Europa is spewing water vapor into space.

If its ocean does host simple life, that means a spacecraft could ‘sniff’ it – and, potentially, discover signs of life.

Go sniff a moon

“The data were there, but we needed sophisticated modeling to make sense of the observation,” said Xianzhe Jia, a space physicist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor whose team has been re-examining data from the Galileo space probe that reached Jupiter in 1997.

Back in 2012, the Hubble Space Telescope found evidence of water vapor vents off Europa's south pole, and did again soon after.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

“We were inspired by those Hubble detections, and realized that one of Galileo’s flybys of Europa was just 124 miles above the region that Hubble saw repeated plumes,” said Jia. “We needed to see whether there was anything in the data that could tell us whether or not there was a plume.”

Old data, new discoveries

Europa’s plumes are likely fed by a subsurface water ocean, or pockets of ocean, under Europa's crust, so a future spacecraft could flyby and investigate their chemical makeup.

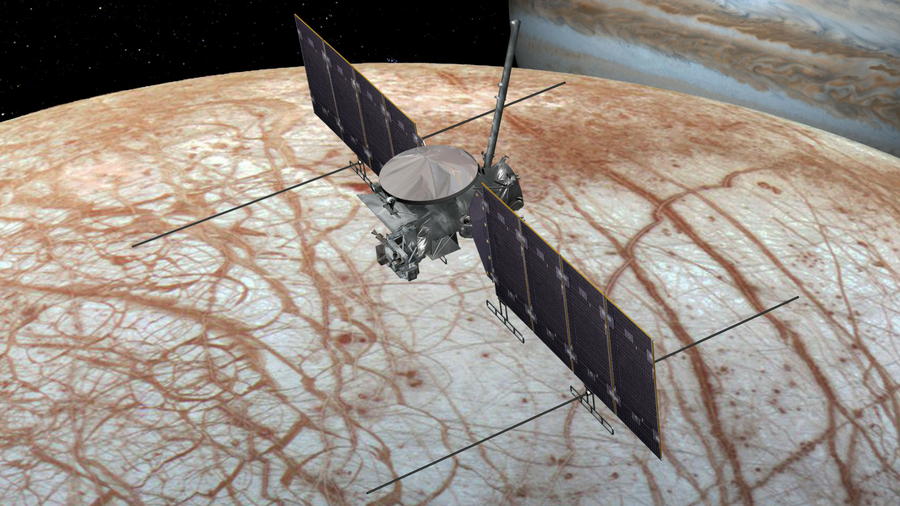

That's what NASA wants to do with its Europa Clipper mission; go sniff a moon. With this new re-examining of old data, NASA can be sure the mission is worth it.

This is not the first time that Galileo's data has been re-visited. NASA researchers have also reviewed historical data collected by Galileo to get closer to discovering why Jupiter’s moon Ganymede – the solar system’s largest moon – has such a bright aurora.

What is NASA planning to do at Europa?

What Hubble and, it seems, also Galileo found on Europa has tantalized planetary scientists, and momentum has since built up for a dedicated mission.

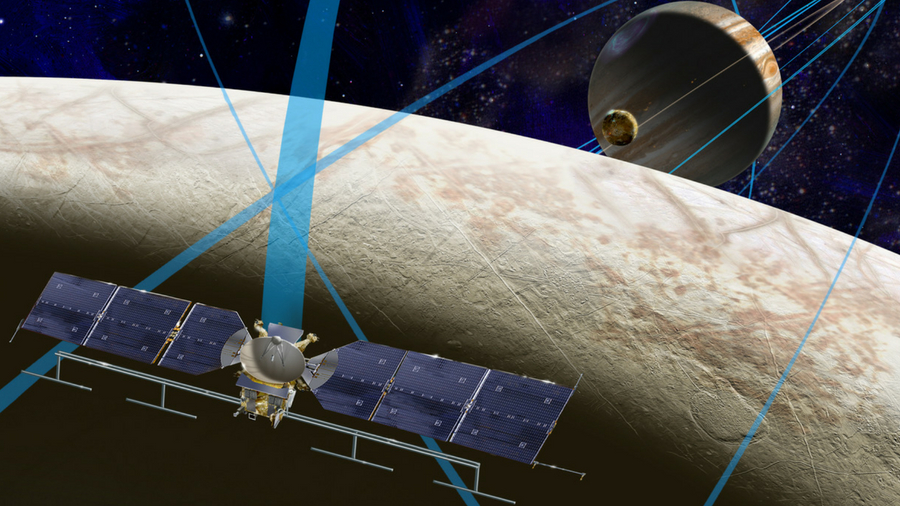

Called the Europa Clipper, NASA's spacecraft will conduct approximately 45 flybys of the icy moon during a three- or four-year mission. Some of those flybys would get as close as 16 miles from Europa's surface.

This is about the search for the ingredients for life. Life as we know it – and that's all we know – requires three things: liquid water, the right chemistry, and an energy source to drive biology.

The Europa Clipper will confirm whether the moon has that subsurface ocean, and search for signs of the other two criteria.

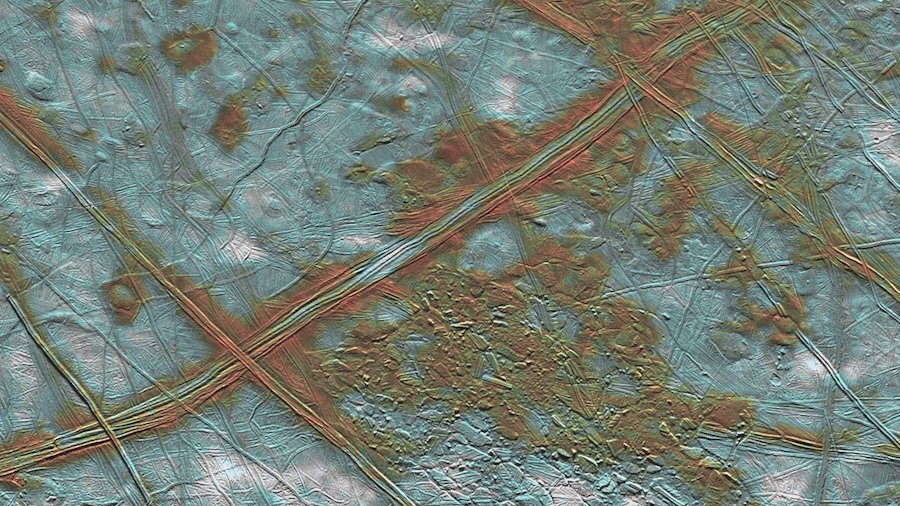

So, the spacecraft will image the moon's icy surface in high resolution and examine the composition and the structure of its interior and icy covering using two ice-penetrating radar antennas.

What is Europa like?

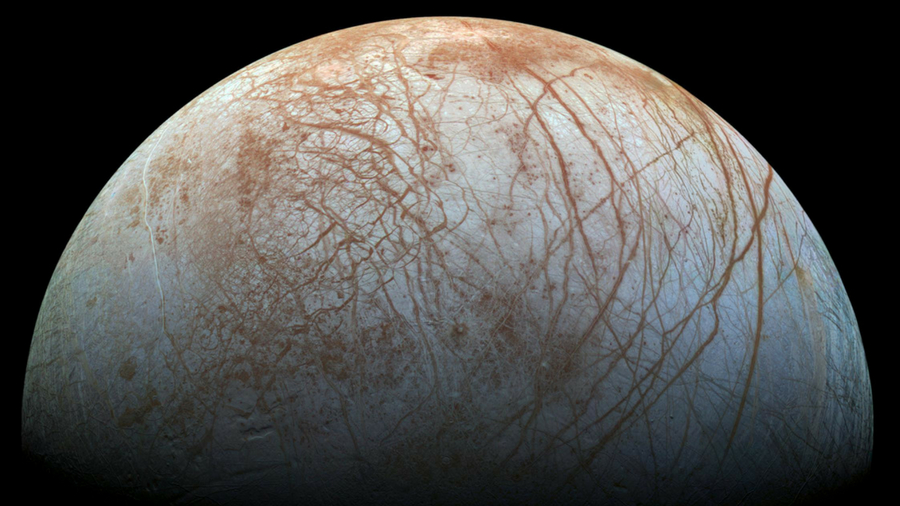

Europa is cold, cracked and chaotic. As cold as -370 F/-220 C at its poles, it's covered in water ice and frozen sulfur dioxide, and it's thought that underneath is a liquid salty ocean.

If that does exist, it probably moves a lot because Europa's ice surges up and down by 50 metres thanks to the gravitational pull of Jupiter.

Europa isn't the only moon in the solar system to have the potential to host life. In 2005, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft discovered jets of water vapor and dust spewing off the surface of Saturn’s moon Enceladus.

When will Europa Clipper arrive?

That depends when it launches, and on what kind of rocket. It’s tentatively scheduled to launch in 2022, but the politics are messy.

The mission must be as cheap as possible and launch on time, which means using a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket is a no-brainer.

Except that, unless the Europa Clipper uses NASA’s own flagship Space Launch System (SLS) uber-rocket – which is overdue, over budget, misunderstood by politicians, and likely to delay the Europa Clipper’s launch until 2025 – Congress might cancel the SLS.

The politics are complex, but suffice to say, the preparation for this mission is likely to be just as much about NASA’s future as it is the search for alien life.

‘The mid-to-late 2020s’ is all we know about the Europa Clipper’s arrival date, because which rocket it launches on will determine how long it takes to get there.

Are there any other missions to Europa planned?

Planned to launch in 2022, the European Space Agency's Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JuICE) will spend three and a half years examining Europa, Ganymede and a third moon, Callisto, all of which are thought to conceal oceans of liquid water beneath their icy crusts.

JuICE will carry cameras and ice-penetrating radar, among other instruments, and detect organic molecules.

At Europa, it will explore its active regions and study the composition of the icy crust, detecting whether there are shallow reservoirs of water sandwiched between icy layers.

How to see Europa in the night sky

It may only be the sixth-largest moon in the solar system, but Europa is a relatively easy object to see in the night sky.

Jupiter has 53 moons in total, but the biggest four – Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto – are known as the Galilean moons.

First spotted by Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei through a small telescope in 1610, absolutely any size of ‘scope pointed at Jupiter will reveal them.

They can also be seen through high-powered binoculars. Now is a great time to do so because Jupiter is at ‘opposition’ – Earth is directly between the sun and the giant planet – making Jupiter the brightest it’s been for 13 months and, technically, since 2002.

So, who will get to Europa first, NASA’s Europa Clipper or the ESA’s JuICE?

Though the launch schedule and thus the speed of the Europa Clipper is up in the air, the set-in-stone ESA’s JuICE is solar-powered, so it will take seven years to reach the Jovian System.

The hunt for alien life is nothing if not a slow-burner, but at least now astronomers know that Europa’s has plumes; the solar system sniff is on.

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),