Are we getting closer to finding 'Planet Nine'?

And if so, what does that mean for us?

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Planets come and go. Remember Pluto? It was the bona fide ninth planet from its discovery in 1930 until its controversial demotion to dwarf planet status in 2006. It's now just one of five dwarf planets in our solar system, the others being Ceres, Haumea, Makemake, and Eris. Semantics aside, the only way we'll get a ninth planet is if astronomers find a new one.

Astonishingly, that's exactly what could happen in the next few years, and there's already new evidence that a hypothetical Planet Nine could actually exist.

When did astronomers first suspect a Planet Nine?

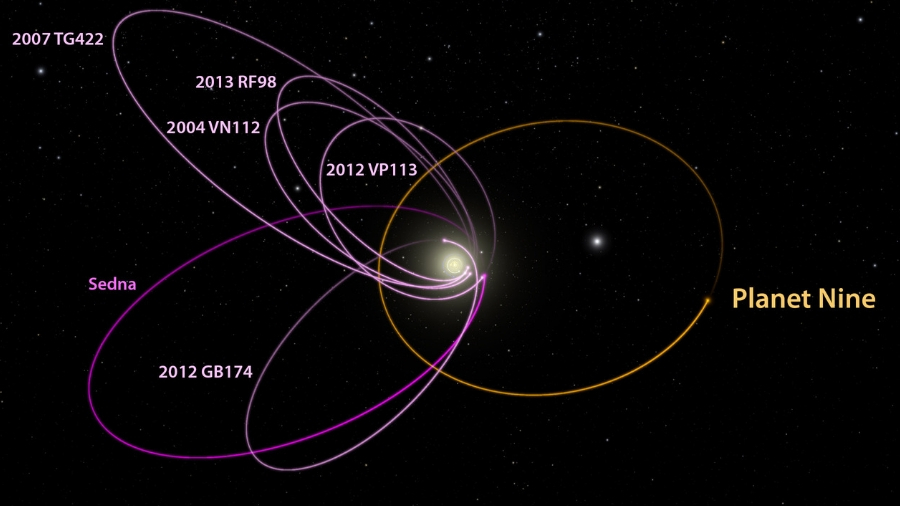

The first recent evidence was presented by planetary astrophysicists Konstantin Batygin and Michael Brown at Caltech in a 2016 paper. Their argument is that the six most distant known objects in the solar system – all in the remote Kuiper Belt region of comets, asteroid and ice way beyond the orbit of Neptune – are physically clustered in the solar system, and for no good reason. These comets and asteroids have elliptical orbits, so every few thousands of years they swing into the inner solar system and loop around the sun.

The weird thing is, their orbits point in the same direction, almost as if they're in sync, and their orbits tilt the same way, too. The paper argues that the probability of all that occurring by chance is 0.007%. Since the original paper was published, more objects with the same characteristics have been discovered.

So what's causing it? They suspect, of course, that the gravitational effects of a distant eccentric planet might be to blame, and are currently using Japan's Subaru Telescope in Hawaii’s Mauna Kea Observatory to study the orbits of outer solar system objects to test their idea, and help define the size of Planet 9.

How big is Planet Nine?

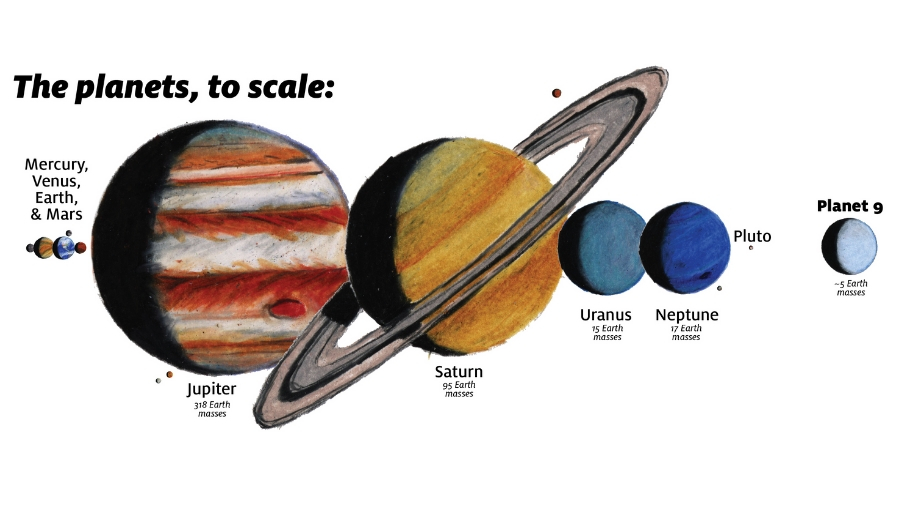

If it exists, Planet Nine literally dwarfs the is-Pluto-a-planet debate. We're talking about a 'super-Earth'. It's thought to be five times more massive than Earth, and its orbit is suspected to be way, way beyond Neptune.

The closest it's suspected to get to the sun is 250 astronomical units (an AU is the distance between the Earth and the sun). The eighth planet Neptune gets to about 30AU. Voyager One and Two, the probes sent on a ‘grand tour’ of the solar system in the 1970s, are currently 145AU and 120 AUfrom the sun.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

If it exists, Planet Nine is going to take some finding.

Would Planet Nine help explain anything else?

The solar system is like a fried egg, with all of the planets orbiting the sun in the same plane. That's why when you look at the night sky you only ever seen planets close to the ecliptic, that east-to-west path the sun takes through the day sky.

However, that plane is inclined by 6° to the sun's equator. Elizabeth Bailey, a student of Batygin and Brown, published a paper also in 2016 that argued that this mysterious spin-orbit misalignment of the solar system is caused by, you guessed it, a Planet 9.

With evidence mounting, astronomers all over the world are now helping out with Planet 9. There are too many studies to mention here, but last summer, an international team of researchers said in a paper that the orbit of a distant object called 2015 BP519 could be perfectly explained by the presence of a Planet 9.

The 'stellar flyby' theory

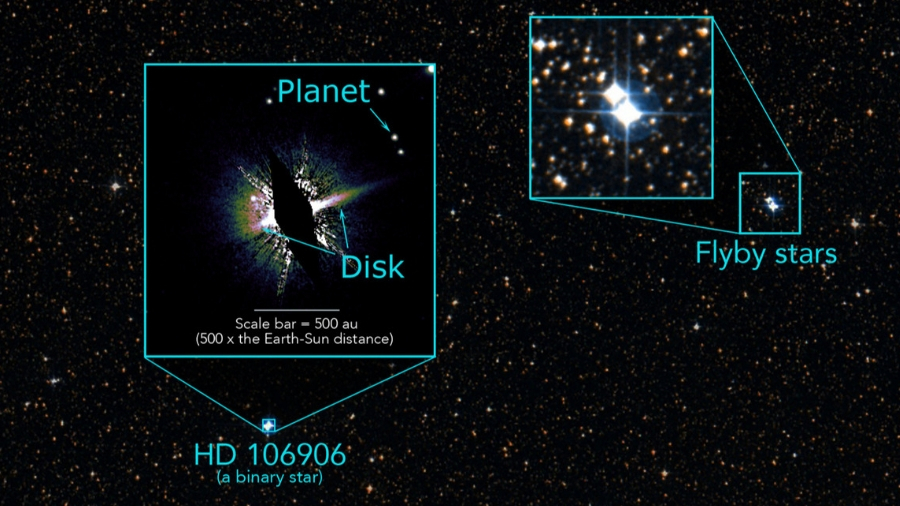

Was the solar system knocked sideways by a passing star? In February 2019, astronomers at UC Berkeley and Stanford University suggest a ‘stellar flyby' theory to explain the solar system's quirks, including its cloud of comets, dwarf planets in weird orbits, and a possible Planet Nine.

"One of the mysteries arising from the study of exoplanets is that we see systems where the planets are misaligned, even though they are born in a flat, circular disk," said Paul Kalas, a UC Berkeley adjunct professor of astronomy who co-wrote the paper.

Kalas studied planets around HD 106906, a young star 300 light-years from Earth. "What we have done here is actually find the stars that could have given HD 106906 the extra gravitational kick […] just like a hypothetical Planet Nine would be in our solar system," he said.

However, while it’s evidence that a large object path the edge of a planetary system can have a big impact, that doesn't mean it happened in our solar system.

Will astronomers find Planet Nine?

Theories are great, but astronomers need to physically find and observe Planet Nine for it to become real. “There are multiple reasons to believe that Planet Nine is real,” says Fred Adams, the Ta-You Wu Collegiate Professor of Physics (and Astronomy) at the University of Michigan after reviewing all of the evidence last month in a paper called The Planet Nine Hypothesis.

He’s optimistic that in the next 10 to 15 years we’ll either be able to observe Planet Nine or have enough data to rule it out. “With its proposed properties, Planet Nine is right on the edge of being observable,” he said.

To put into context just how difficult that's going to be, in November 2018 astronomers again using the Subaru Telescope discovered the most-distant body ever observed in the solar system. Called 2018 VG18, it's 120AU distant, which is possibly only a third as far away as any Planet Nine.

How do we find Planet Nine?

"It's a very dim object in a very big sky," says Adams. "Since we don’t know exactly where it is, you have to survey the whole sky, or at least large portions of it, in order to find the planet [...] I think by 2030 we will have seen it or will have a better idea of where it is."

Until the next generation of super-space telescopes makes it into orbit, Planet Nine is probably going to remain a theory, but you can help. The Backyard Worlds: Planet 9 project is calling on citizen scientists to join the search for ‘cold worlds’ orbiting the sun by browsing images from NASA's WISE satellite, which is currently surveying the entire sky in infrared.

It won’t be easy to spot, but with a predicted ten thousand year orbit of the sun, at least Planet Nine isn’t going anywhere fast.

Welcome to TechRadar's Space Week – a celebration of space exploration, throughout our solar system and beyond. Visit our Space Week hub to stay up to date with all the latest news and features.

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),