NASA’s incredible plans for six space telescopes all 'better than Hubble'

From sunshades and x-rays to finding life on exoplanets

Are we about to enter a new golden age of astronomy? Some would argue we are already in one, with the Hubble Space Telescope sending back incredible images of the Universe since the 1990s. However, designing, planning, building and launching a space telescope can take 20 years. Hubble may now be on its last legs, but astronomers already have the James Webb Space Telescope (almost) ready to go, and even its successor, WFIRST.

So what comes next? With astronomers desperate to take a closer look at distant exoplanets to search for life, and technology rapidly advancing, plans are afoot for no less than four more space telescopes.

Although they’re not due to fly until 2035, later this year the Decadal Survey will advise NASA which ones to green-light. Either way, what we know about the universe is about to drastically change.

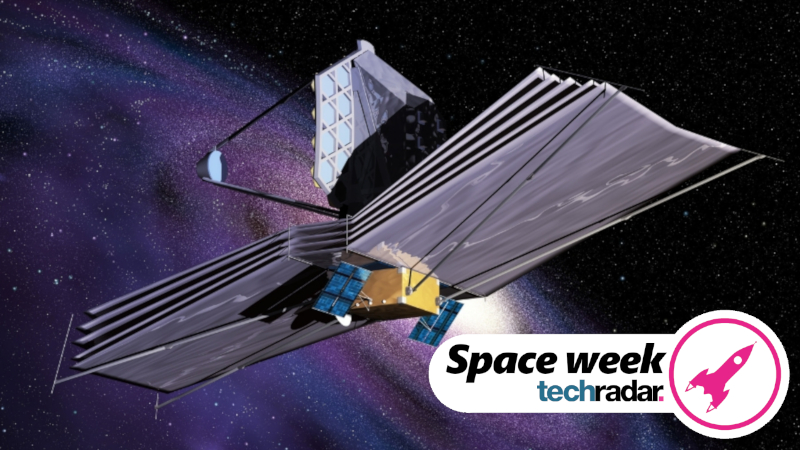

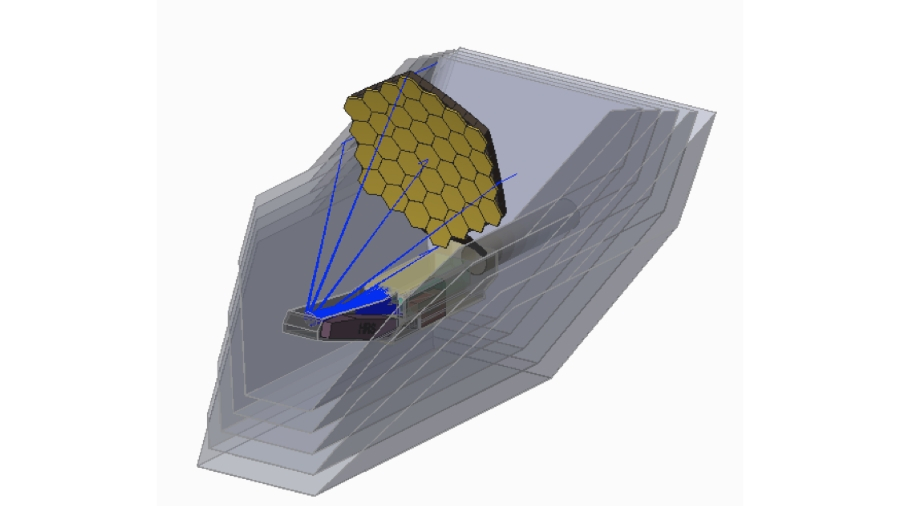

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST)

- Status: final testing

- Official website

Known as Webb or JWST, this mighty space telescope is an international program by NASA, the European Space Agency and the Canadian Space Agency. Costing around US$10 billion so far, the Webb will have a set of mirrors that together measure 6.5m.

That's a lot larger than the Hubble telescope, but what differentiates web from Hubble is not the size of the mirror, but what it can see. With a near-infrared camera and spectrograph, it will be able to peer back into the early universe, but it's also 100x times more powerful; think of it as being able to zoom in on the universe to create far more detailed images than Hubble can manage.

Tragically, it was supposed to be 1.5 million km from Earth by now, but delays mean it's now not scheduled to launch until 2021. It's also only designed to work for between five and 10 years, so however impressive Webb is, it's probably not going to become as iconic as Hubble.

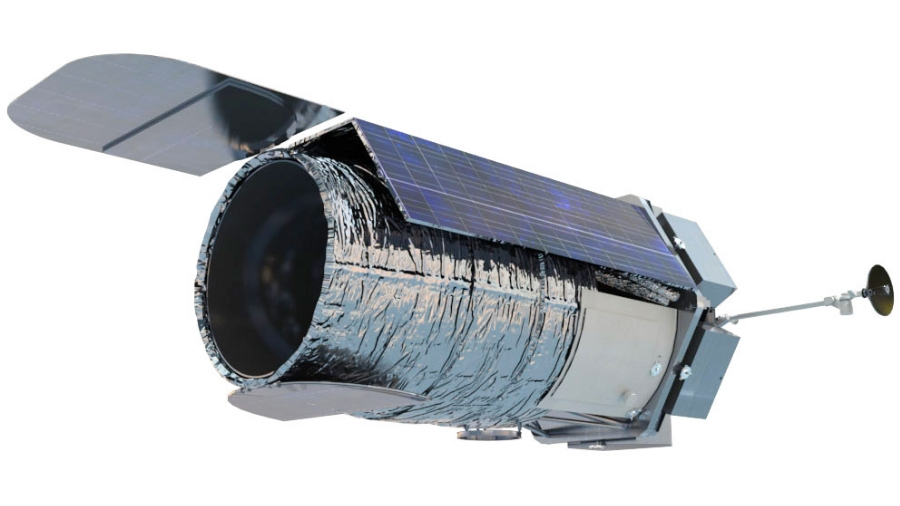

Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST)

- Status: under development

- Official website

Due to launch in the mid-2020s, the WFIRST is a $3.2 billion (about £2.4 billion, AU$4.5 billion) NASA observatory that has the same 2.4m mirror as Hubble, but with a number of exquisite improvements.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

It's actually modeled on an old space telescope that never made it to space, which will be fitted with a wide-angle lens to give it 100x the field of view of Hubble. It's also going to have a coronagraph, which will allow it to block out the light from a star to better see small, Earth-like planets orbiting close to their host sun. It will also look deep into the infrared, so will better see what the universe is actually like … and maybe help figure out what the heck dark matter and dark energy are.

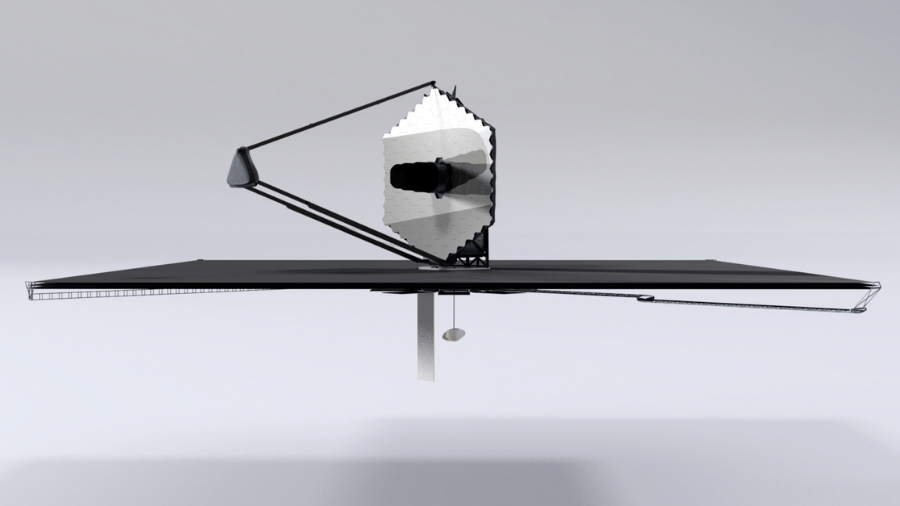

The Large UV/Optical/IR Surveyor (LUVOIR)

- Status: Decadal Survey Mission Concept

- Official website

In the last decade, astronomers have found many thousands of exoplanets, but do they contain life? Is life everywhere in the universe? Or is there a limit?

LUVOIR will tell us. It’s the big one, physically, scientifically and financially. If WFIRST is a relatively affordable stop-gap, the Large UV/Optical/IR Surveyor will become a true all-rounder like Hubble, but 40 times more powerful.

Designed to launch in 2039 and observe for several decades, possibly with a 15m mirror (which would make it bigger than any present ground-based telescope), it's the best, the priciest, the fastest and the longest-lasting of all the space telescopes planned by astronomers.

Want to directly photograph distant exoplanets? LUVOIR. Study their atmosphere for bio-signatures like oxygen and methane? LUVOIR. Closely study the planets and moons of our solar system and compare their atmospheres to distant worlds? LUVOIR.

Studying the cosmos in ultraviolet, optical and infrared, LUVOIR will be the space observatory to beat all others. It's even been made in Lego, which is a start. However, at a yeah-right $8 billion (about £6 billion, AU$11 billion) price tag before the inevitable price rise, LUVOIR could well prove to be just too expensive for NASA to commit to. There's also presently no rocket big enough to carry it into space.

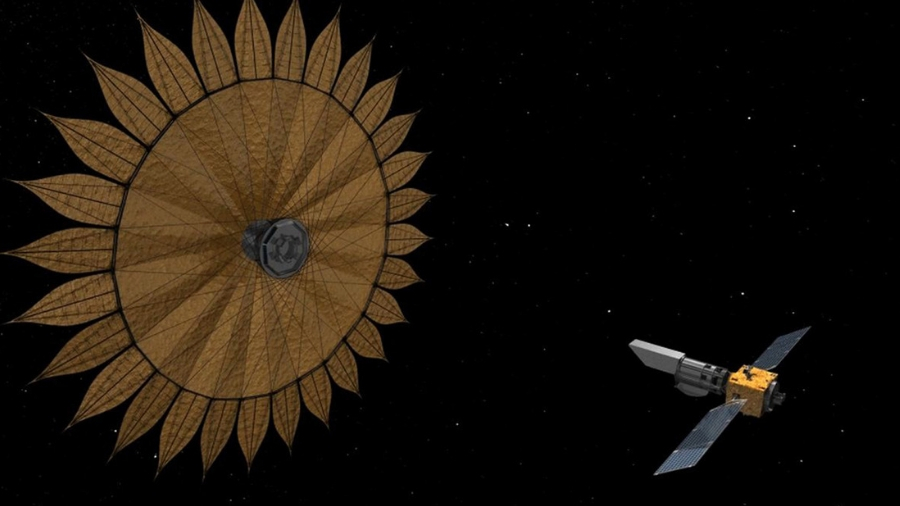

Habitable Exoplanet Observatory (HabEx)

- Status: Decadal Survey Mission Concept

- Official website

Kepler discovered 2,300 exoplanets – mostly huge 'hot Jupiters' – in just two tiny patches of the night sky, proving that one-trick space telescopes can be utterly revolutionary. However, although HabEx is designed primarily to directly photograph exoplanets, this is far from a basic proposition.

Designed to last for five years, HabEx will be the first telescope to be able to find, and study, Earth-like planets. These are incredibly faint objects (10 million times dimmer than their host star), so the headline feature on HabEx is a starshade. A foldout, flower-shaped 72m diameter device designed to orbit 100,000 km away from the telescope, but aligned with it, the starshade will act as a coronagraph to suppress light from stars so that the telescope can find exoplanets more easily with its 4m mirror.

As well as identifying one-pixel-wide exoplanets, HabEx will be able to study their atmospheres and look for signs of life. HabEx's starshade is a bit of a leap into the unknown, but its proposers argue that it could just as easily be aligned to the Webb or Hubble.

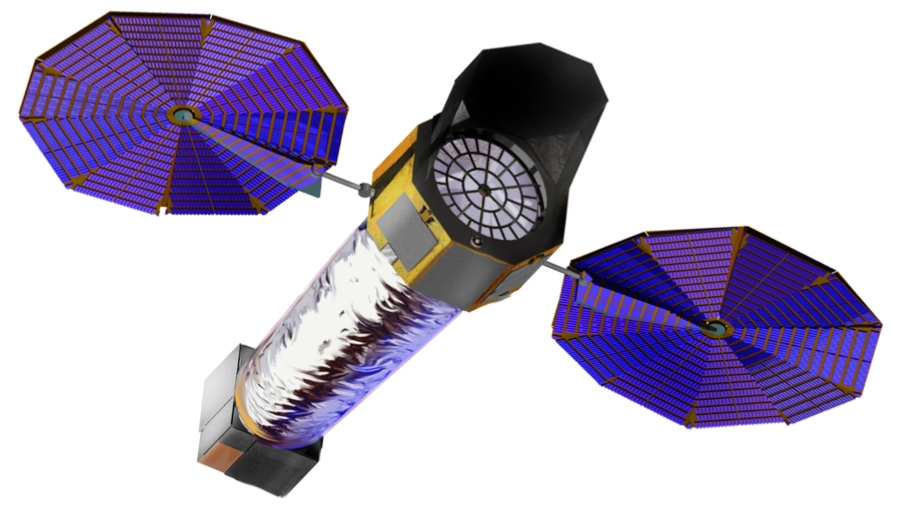

Lynx X-ray Surveyor

- Status: Decadal Survey Mission Concept

- Official website

The Lynx is another one-trick telescope, this time designed to 'see' the invisible universe. What do we know about super-massive black holes in the early universe? Almost nothing, except that they are much bigger than they should be. Cue the Lynx telescope, which is an attempt to capture x-rays from black holes, as well as from supernovae and gas from galaxies. X-rays usually fly straight through mirrors, and can't be detected at all from Earth, so Lynx will use an array of hundreds of tiny curved mirrors to deflect x-rays onto detectors.

Designed to be a successor to the NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory in around 2035, Lynx stands for… actually, it doesn't stand for anything. It's just that a lynx is "a symbol of great insight with the ability to see through solid objects to reveal the true nature of things". Fair enough.

Lynx is best thought of as a kind of partner telescope to the Webb.

Origins Space Telescope (OST)

- Status: Decadal Survey Mission Concept

- Official website

Where did life's ingredients come from? How did water get to habitable exoplanets? A space telescope capable of seeing in the infrared, except 1,000 times more sensitive than any other telescope, Origins is designed to study how the Universe developed. It will also be super-fast, using a mighty 9.1m mirror to scan the same area of sky in a single second that the Webb would scan in two minutes. Uniquely, Origins would be serviceable by astronauts – to fix or upgrade it – because it will orbit near the moon where NASA is planning a Lunar Gateway.

Origins will be able to see back in time to just 500 million years after the Big Bang to study how the Universe developed, and where the likes of carbon, oxygen and nitrogen came from. It will also be able to detect the chemical make-up of the atmospheres of exoplanets, study galactic gas clouds, and detect anything else that's dim and distant.

To do all that, Origins will need to be kept at a temperature of 4.5 Kelvin, which is about -268.6C/-451.6F.

Welcome to TechRadar's Space Week – a celebration of space exploration, throughout our solar system and beyond. Visit our Space Week hub to stay up to date with all the latest news and features.

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),