Why 3D printing will save your life one day

It's far more than just making little toys

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The simple fact is really sick and desperate people are left frustrated by modern medicine for a number of reasons.

Those seeking transplants have to wait on long lists, and if they do eventually find a donor, their body might reject the tissue. Patients in need of casts or equipment to help them heal often only have expensive choices made of heavy materials.

And those in developing countries don't have access to the medication they so desperately need — often resorting to black market options that are unreliable and dangerous.

These are only a small handful of the problems that 3D printing could eradicate completely, creating personal, bespoke solutions that are tailored to each patient, where materials are light and comparatively cheaper than traditional options. And crucially, 3D printers can be taken anywhere, so those in remote locations aren't left without - and they can even print hair.

What does the future hold?

3D printing is already giving amputees a new lease of life and turbocharging healing time with tailor-made super-healing casts, but the future looks even brighter and more exciting.

We're not even talking about the 'boring' consumer applications, where digital rights management will allow us to print something like a new pair of glasses for yourself without having to pay an optician, book an appointment and waste time at a fitting - although even that is revolutionary.

The same can be said for medical equipment. There's a lot of noise around 3D printed human tissue, but 3D printing can also be used to improve the way doctors carry out procedures by arming them with ground-breaking equipment.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Whether that's printing a tiny 3D printed medical three-lens camera that can fit into a syringe or projects like iLab Haiti, an initiative that brings 3D printers to Haiti allowing basic but important equipment to be printed with ease, the more obvious ideas for 3D printing are very real possibilities.

But what's the future of the technology - could it change the face of healthcare forever? We spoke to a number of industry insiders to find out what's to come – instead of casts and legs, could we one day be using them to print an entire human from a chunk of DNA, à la The Fifth Element?'

Why medicine really needs 3D printing

It feels like every day a new 3D printing medical "miracle" makes the headlines, but one of the most widespread examples of printing already being used in a number of medical establishments is to create prosthetic limbs (hell, even this dog has 3D printed legs) and state-of-the-art casts that heal broken limbs up to 80 percent faster.

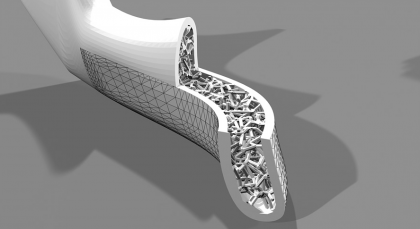

Jesse Harrington-Au, 3D printing expert at global 3D design software company Autodesk, told us the reason printed prosthetic limbs are so revolutionary is three-fold.

"They're a fraction of the weight of traditional prosthetics as they're made using lighter nylon or titanium meshes, instead of heavy, mass-produced solid plastic. They're also easily customised to the user's body, which not only radically improves comfort but also means they can be designed with fashion in mind, helping empower individuals, especially kids."

He added: "3D printing is also drastically lowering the cost of prosthetic limbs to as little as $70/£50. Limbs made using traditional manufacturing techniques can cost thousands of pounds, putting them out of reach for many people."

It doesn't stop there though: the wide-ranging possibilities for personalisation in 3D printing means you could print prosthetic limbs that behave even more like human limbs — or are actually more superhuman.

For example, a heat sensor being printed into a prosthetic arm could let the user "feel" sensations in a new way. Or a 3D printed leg with a tracker could help users take the quantified-self obsession to a whole new level.

Harrington-Au told us: "Soon we'll start to see limbs fitted with a range of sensors and other electronics. For example, prosthetics could be fitted with heat sensors, heart monitors that can act like a built in FitBit, or even a torch.

"These sensors and additions not only assist in creating more human acting hands but also can help to enhance the user."

Prepping for surgery with a printer

3D printing could revolutionise surgery itself but before that happens it'll be used to help plan procedures in a whole new way, giving surgeons information they've never had access to before.

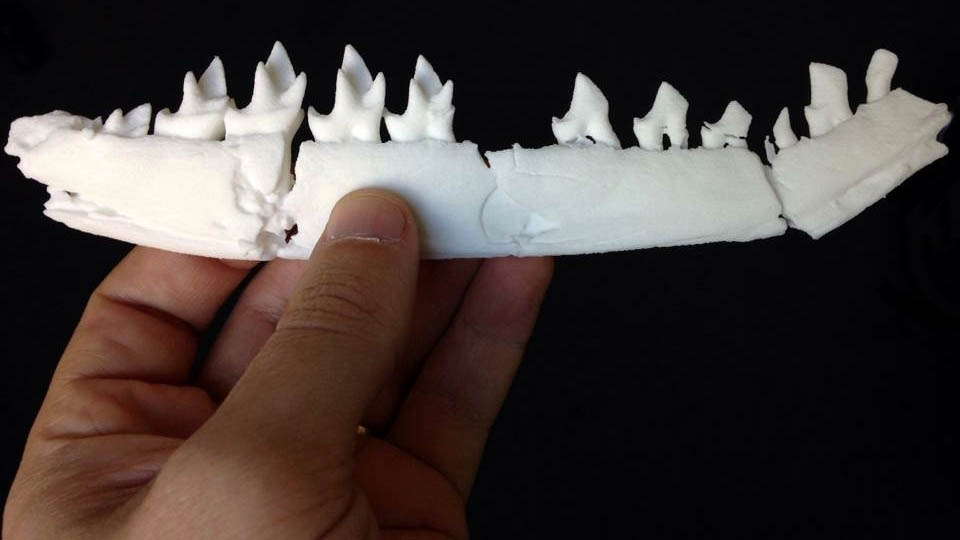

A number of doctors are already using 3D printing to construct real-life models of patients in order to better inform their surgical decisions - recently doctors created a 3D printed model of unborn baby Conan Thompson, to assess whether he'd need surgery in the womb.

Glenn Green, one of the doctors who worked on the case, explained: "The 3D printed model of the foetus allowed us to actually see in person what it looked like and have something in our hands to help us decide the best way to care for the baby."

Although every expert we spoke to was excited about the prospect of futuristic concepts like printed organs, they all agreed that 3D printing these planning models was what could actually make the biggest difference.

Although there are already a few examples of 3D printed models being used to inform surgery, in the future we can expect this to become widespread and commonplace — even for the most basic procedures.

Bioprinting new organs, skin and ears

Up until now, a number of researchers have only begun printing small quantities of human cells and synthetic skin. But recent advancements in 3D printing tech mean these cells may soon actually withstand being transplanted onto a human and behave like human skin and organs.

Back in February, a research team led by Anthony Atala from Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine unveiled an innovative 3D bioprinter called the Integrated Tissue and Organ Printing System (ITOP). The bioprinter uses living cells as 'ink' and injection nozzles that follow a CT scan blueprint to create a bespoke body part, like muscle, bone or even organs.

A similar kind of technology has been developed by researchers from the RIKEN Centre for Developmental Biology in Japan. Their focus has been on creating skin grafts that actually behave like living human skin, 'creating' stem cell-like structures and convincing them to perform like the skin they'll need to replace.

Lead scientist Dr Takashi Tsuji, from the RIKEN Centre for Developmental Biology, said: "Up until now, artificial skin development has been hampered by the fact the skin lacked the important organs, such as hair follicles and exocrine glands, which allow the skin to play its important role in regulation. With this new technique, we have successfully grown skin that replicates the function of normal tissue."

Similarly, Researchers at Cornell University have pioneered a way to use cells from cows in order to grow cartilige that can then be moulded into an ear shape and transplanted onto patients who have lost ears to cancer or in accidents.

So far these skin cells, homegrown organs and cow ears have only been tested on lab animals, but the next steps are obviously creating ones that can be transplanted to humans safely - and it's in the lab that the first victories will be found.

Simon Shen, CEO of leading 3D printer brand XYZprinting, told us: "Printing whole organs for transplant is something that might be possible in the distant future, but more immediately printing skin cells and pieces of tissue to test drugs could be viable within five years."

Not only is human transplanting next on the list, but so is using the patient's own DNA. And this is where 3D printing will become even more effective.

Printing pills

One area that's had a great deal of attention and research is 3D printing medication — as well as the designs they come in.

Last year the FDA in the US approved the first 3D printed drug, but in the future we can expect all kinds of medications to be printed quickly, cheaply and on demand.

The reason drug printing has garnered so much interest is because there are so many challenges when it comes to creating and distributing medication today.

These include creating customised shapes (required to administer drugs in specific ways for different conditions), tailoring medication to a patient's needs and cutting costs and stopping the rise in counterfeit drugs in developing worlds.

Simon Shen told us: "The true advantage of 3D printing in pharmaceuticals is this capacity for personalisation."

He continued: "3D printing can create any number of unusual shapes of pills that standard production techniques find difficult. The surface area of these different shapes (and therefore the duration of drug release) can be adjusted for various patients' needs.

"Some patients need fast acting medication, whereas others need gradual release over a longer period of time – 3D printing can create shapes specific to these requirements."

Clive Roberts and his team of researchers at Nottingham University have been working on 3D printing a polypill. This means a single pill that contains numerous drugs with different release profiles, which would be hugely beneficial for those who have to take more than 50 pills a day, like the elderly or those with HIV.

What are the drawbacks?

When it comes to printing drugs, the problems are pretty obvious. In a world where medicine is digitised, what would stop a drug being shared online, with people using the technology to print narcotics? After all, some area already printing 3D guns.

For printed drugs to work, it would have to be heavily regulated and controlled by pharmacists or other medical experts.

Professor Lee Cronin, Regius Chair of Chemistry at the University of Glasgow and TED Talk speaker spoke to Gizmodo about this topic in-depth and explained: "If someone went to a local hardware store right now, they could buy the chemicals and the equipment to make all sorts of drugs.

"It would take them ages, and they'd get in trouble, and it would still be illegal. And, in the end, they wouldn't have a pure substance that they should trust anyone to take."

He continued: "Will [this technology] increase access to [illegal] drugs? No, it will not change anything fundamentally from what is possible illegally now. But what it aims to do is dramatically lower the cost of drug manufacturing and open up access to the world to medicine - it would allow the entire inventory of known drugs to be made again, even if they are 'out of print', i.e. not being made today in a big manufacturing facility.

"[But even if it could be used illegally], the thought experiment is: how many millions of people suffer from drugs problems? And how many billions of people die because they have no medicine?"

Everything we have but better

Even if all of these problems are ironed out, some of the developments highlighted above could still be years away. This is due to the fact many of these ideas will need rigorous testing – after all, you don't want a new 3D printed heart if it's not likely to stand the test of time.

We've only scratched the surface about what the future of 3D printing in medicine will bring. But let's not overlook some of the 3D printing tech that's already in use.

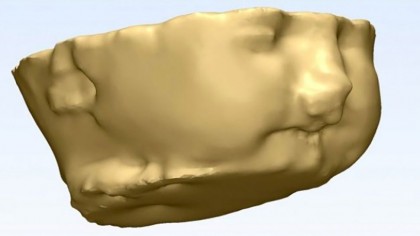

Simon Shen told us: "Right now we are already seeing SLA 3D printing being used in dental work – dentists producing their own crowns, bridges and orthodontic devices at the touch of a button, which match every groove and curve. That's something that I expect will come further into the mainstream very soon."

So although this is a really simple application of 3D printing in comparison to some of the more ambitious research projects we've covered, it's important to remember that advances will see techniques and technology improve, become more accurate, more effective and mainstream.

Brigitte de Vet, vice president of Materialise Medical: "In the future, 3D printing in medicine will no longer make the headlines, except in the most exceptional cases, because it will actually be an expected and accepted standard of care."

"Much like you expect to be given anaesthetic before a surgery, people undergoing complex operations will expect that their surgeon has used 3D printing in the planning stage of the procedure, perhaps using 3D printed surgical guides to translate that plan into the operating room, or even using 3D printed, customised implants."

Of course, with such huge developments, like printing organs and skin, don't come without their their own challenges and ethical implications. But as Cronin says, the bottom line is that more and more people will be saved, which is what's really important - provided the technology keeps advancing.

Becca is a contributor to TechRadar, a freelance journalist and author. She’s been writing about consumer tech and popular science for more than ten years, covering all kinds of topics, including why robots have eyes and whether we’ll experience the overview effect one day. She’s particularly interested in VR/AR, wearables, digital health, space tech and chatting to experts and academics about the future. She’s contributed to TechRadar, T3, Wired, New Scientist, The Guardian, Inverse and many more. Her first book, Screen Time, came out in January 2021 with Bonnier Books. She loves science-fiction, brutalist architecture, and spending too much time floating through space in virtual reality.