The biggest space moments and discoveries of 2015

Flowing water on Mars, Earth 2.0 and Pluto among the highlights

Introduction

Much of the world's attention right now might be focused on the goings-on of a galaxy far, far away, but a lot happened in our own humble galaxy this year that's worthy of celebration as well.

Following setbacks like the end of the Space Shuttle program, space exploration has awakened with renewed force. Summer in particular grabbed headlines, as startling images came in from a demoted planet, a huge earth-like world was discovered many light years-away, and we learned that one of our planetary neighbors isn't quite as hostile to life as we thought.

We've compiled a list of the most noteworthy discoveries here, but big news from the cosmos was still coming in as recently as last week. At the rate things have been going, there's still plenty of time for another celestial shocker before 2016 arrives.

SpaceX rocket does the impossible

With only a handful of days left in the year, a new era in space exploration began last week when Elon Musk's SpaceX firm completed a vertical landing of the 15-story first stage of its Falcon 9 rocket upon its return from around 200 kilometers up in space. All previous attempts by SpaceX occurred on barges in the ocean with no success, but December 21's landing took place on a landing pad at Florida's Cape Canaveral without a hitch. You can watch the jubilant footage here.

The rocket also successfully deployed 11 communications satellites into orbit.

Why is this such a big deal? Rocket stages and engines usually burn up upon reentry into Earth's atmosphere. With reusable rockets, though, the cost of space travel goes down significantly. Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin company also managed to land one of its shorter New Shepard rockets in West Texas last month, but the stakes were considerably different since the New Shepard only reaches a maximum height of around 102 kilometers and travels about half as fast as the Falcon 9.

Pluto is endlessly fascinating, planet or not

Years after being demoted as a planet by the International Astronomical Union (IAU), Pluto got its revenge of sorts when 2006's New Horizon probe arrived in July and revealed that the far-flung sphere and its largest moon Charon were much more than barren, forgettable rocks.

The resulting photos show a surprisingly active planet, crowned with polar caps made of nitrogen and methane gas and stamped with a heart-shaped plain that's mysteriously free of craters. We now know that Charon is relatively smooth as well, and dominated by a large red splotch that's informally known as "Mordor." Until recently, the news from NASA focused on "big picture" images from the probe, but far more detailed photos have started to pour in over the last few weeks.

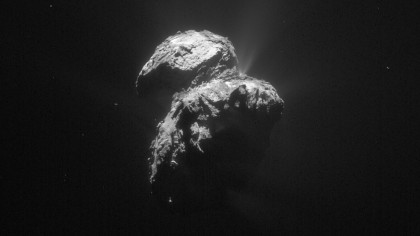

We learned a lot about comets - by riding one

The European Space Agency's Philae probe made headlines last year when it became the first probe to make a soft landing on a comet's nucleus, but the fanfare fell flat after a botched landing and weak batteries sent Philae into Safe Mode soon after. It awoke again on Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko in June, though, shooting off several transmissions to its orbiting companion spacecraft Rosetta before going silent again in July.

That and other data gathered by the two crafts change our perception of comets. The discovery that water found on the comet has more mass than that found on Earth, for instance, appears to disprove a theory that comet bombardment originally brought water to our home planet. New findings suggest that comets may have helped spark life, though, as Philae discovered 16 organic compounds on its host - enough to create a "primordial soup" in the right conditions.

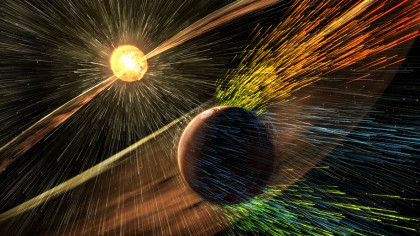

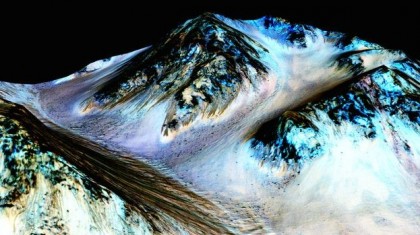

There's flowing water on Mars, sometimes

Observers have been imagining that water exists on Mars ever since Percival Lowell mapped out supposed "canals" on our ruddy neighbou's surface in the 1890s. Decades of bleak photos of the planet's harsh surface dampened such hopes, but NASA revealed in September that liquid water does, in fact, still flow down Mars' valleys and craters in the summer months.

No one really knows where the water comes from or if there's any life associated with it, but infrared data from spectrometers and numerous photos depicting "slope linea" attest that surface water exists beyond a doubt. It's also in the air, and the European Space Agency and Russia's Roscomos recently revealed that they'll use a 2018 mission to experiment with a way to pull water from the atmosphere for greenhouses and future human consumption.

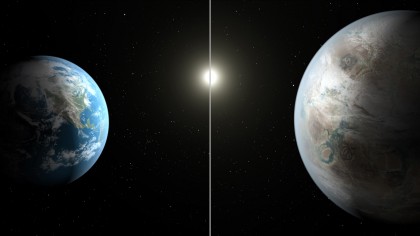

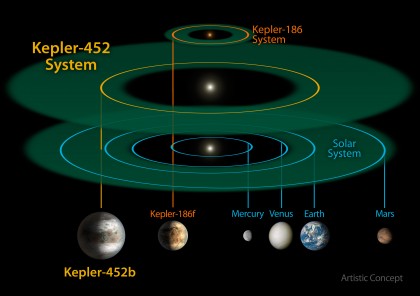

We found a huge Earth-like planet

Most of the 1,000+ worlds found in the recent surge of planetary discovery have been either looming gas giants or situated in spots that would make living on them more than a little uncomfortable. In June, though, NASA announced the discovery of Kepler-452b, and it says it's the most Earth-like planet found to date.

Mind you, that doesn't necessarily mean it's carpeted with lush forests and vacation-worthy beaches. It could easily be as dead as disco, and its slightly larger size than Earth leads some scientists to doubt that it's even rocky. Everything else checks out, though, whether it's its cozy spot in the star's "habitable zone" or its pleasantly familiar 385-day year. Alas, Kepler-452b is 1,400 light years away, so don't expect a follow-up probe for more concrete data anytime soon.

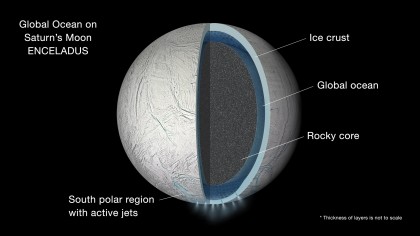

There's probably a worldwide ocean under Enceladus

When it comes to the solar system, it seems as though there's water, water everywhere if we can only figure out how to look for it. Scientists have known for a while that Jupiter's moons Europa and Ganymede have subsurface oceans, but new data from the aging Cassini probe helps prove that one of Saturn's moons is a veritable waterworld of its own.

NASA already knew that over 100 polar geysers on Enceladus spew icy jets into space, but the new data show the moon wobbles in its orbit, which is almost certainly the effect of heavy tidal forces acting on a liquid global ocean below the icy surface. It gets better: recent samples from the plumes suggest that this relatively unknown corner of the solar system might be one of the best places to look for life aside from Earth.

Two guys are spending a full year in space

Years of science fiction and the relative frequency of modern space missions have accustomed many of us to the idea of long-term life on a spacecraft, but the truth is that until now almost all visits to space have lasted only a few weeks or months. But this year, American astronaut Scott Kelly and Russian cosmonaut Mikhail Kornienko were sent up to see what happens when we stick around longer.

They're both spending a full year on the International Space Station in order to study the effects such long-term exposure to space has on the human body, and they're already a little more than eight months into the trip. Kelly in particular has become something of a Twitter celebrity on account of his frequent photo posts. As fun as it sounds, the danger is high - NASA claims that you'd need to fly from Los Angeles to New York 5,250 times to get the same radiation exposure Kelly and Kornienko are living through.

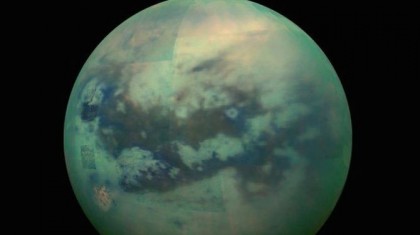

We got one of our best views of Titan to date

Saturn's Titan is the only moon in the solar system to have a thick atmosphere like we find on Earth, but it's usually smothered in an impenetrable toxic haze (sort of like what you'll sometimes find hovering above Beijing). We got one of our best views of Titan ever, though, when the Cassini probe shot by on November 13 to check out its surface in near-infrared wavelengths that allow better glimpses of the surface than straight visual images. The result? We now have our best photos to date of the dunes, rivers, and lakes that cover its surface.

Indeed, the new photos make it look almost habitable, but the catch is that the surface temperature hovers at around −179 °C and all those lakes and rivers contain methane instead of water. It's not exactly the closest imagery we've seen from Titan, though. Back in 2005, the Huygens spacecraft beamed back images of the surface for 90 minutes before winking out into oblivion.

Trusty probe meets fiery death - on purpose

The MESSENGER probe spent four years hiding behind a heat shield while it studied the planet Mercury a mere 48 million kilometers or so from the sun, so it's only appropriate that it went out in a blaze of glory. Late in April, NASA willingly sent the probe to crash on a relatively smooth area of the surface at 14,000 kilometers per hour in the hopes that a scheduled 2024 probe from the European Space Agency and Japan will be able to study the visible effects of a relatively recent impact crater. The probe was responsible for almost everything we know about the closest planet to the sun, and it transmitted data until just 10 to 15 minutes before the end. As a farewell gift, it sent back a final set of colorful spectrometer images that yielded some insights into the planet's atmosphere and surface composition.

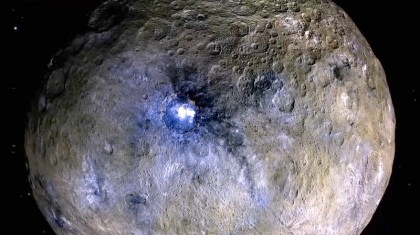

The bright spots of Ceres were demystified

When the Dawn space probe settled into orbit last March around Ceres (the largest body in the asteroid belt between Jupiter and Mars), it sent back photos of mysterious bright spots pocking the dwarf planet's surface. Astronomers had known about a bright spot on Ceres ever since the Hubble Space Telescope captured blurry images of it back in 2003, but the mystery only intensified after Dawn revealed multiple such spots.

Humanity being humanity, some commentators insisted we were seeing the lights from alien cities. The truth, it seems, is a tad more mundane. Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research claimed earlier this month that the spots largely originate from deposits of salty hexahydrite, a form of magnesium sulfate that's apparently mixing with briny frozen water on Ceres. Asteroid impacts bring the strange mix to the surface, and it ends up reflecting around 50% of the sunlight that hits it.

First 'supermoon' lunar eclipse in 33 years

Not all of the big events from space this year required fancy probes worth millions of dollars to enjoy directly: one, at least, was visible almost everywhere (apart from Asia and Australia) just by walking outside. September saw the most recent appearance of a "supermoon" lunar eclipse, which is a sensationalist-friendly nickname for a perigree full moon eclipse. Lunar eclipses themselves aren't terribly uncommon - there will be another one next March - but September's eclipse occurred when the moon was at or near its closest point to Earth, rendering the moon itself abnormally bright, large and red. Until this fall, we hadn't seen a supermoon lunar eclipse since 1982, and we won't see another until 2033. In other news, a solar eclipse occurred near Iceland in March, resulting in some fantastic photo opportunities.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful