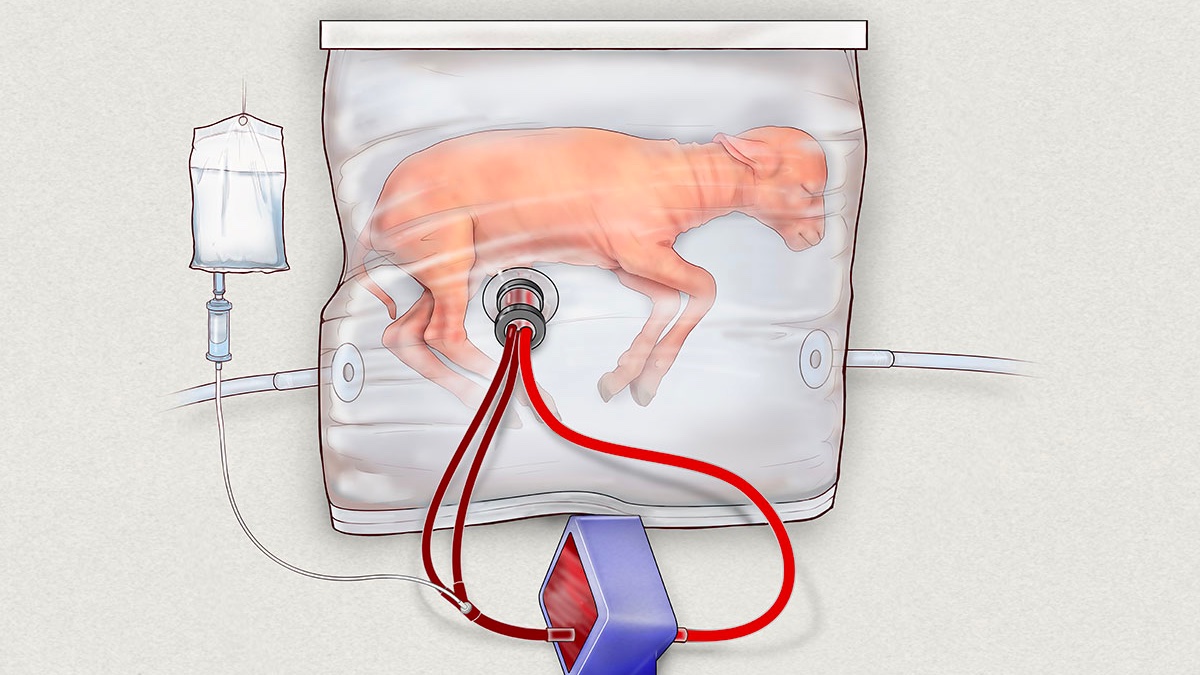

A lamb foetus grew in this artificial womb for four weeks

Womb with a view

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Premature birth is the most common cause of death among infants worldwide. About 15 million babies (five to twenty percent of the total) are born pre-term each year.

Over the years we've got better at caring for those infants, and survival rates have risen, but those who survive are still at risk of infections, lung damage and lasting disabilities.

Now, however, a team at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia has developed an artificial womb that has been tested on premature lambs and could be used for human babies within the next three years.

Plastic bag

The artificial womb is essentially a fluid-filled plastic bag. The fluid is made of water and salts, just like in a real womb, and the bag is sealed to protect the foetus from infection.

Instead of a placenta, an oxygenator is connected to the umbilical cord so that the creature's own heart can work to collect oxygen. It's hoped this will prevent lung damage from the ventilators currently used for premature births.

In tests with animal embryos, lambs that were 15 and 17 weeks into the normal 21-week gestation process for sheep were removed by caesarean section, placed into the bags and then monitored.

They were kept there for four weeks, after which some were "born", removed from the bags and weaned on bottles. The oldest is now a year old and "doing well", the team says.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Other lambs were euthanized after the four weeks and examined, all of which appeared to show healthy development with no abnormalities. "These animals are, by any parameter we’ve measured, normal,” Alan Flake, who led the study, told New Scientist.

Dark interior

The challenge is now to develop a version of the technology for human babies, which the team believes can be done in three to five years. Getting there will involve improving the amniotic fluid substitute, adding foetal urine, nutrients and growth factors to the mix.

It'll also look different. "I don’t want this to be visualised as fetuses hanging on the wall in bags,” Flake said, adding that it'll look more like an incubator with a dark interior, albeit equipped with cameras so parents can see their newborn.

The full details of the discovery were published in Nature Communications.