Interview: Peter Molyneux on Natal

How Dickens' "Penny Dreadfuls" inspired Fable 3

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

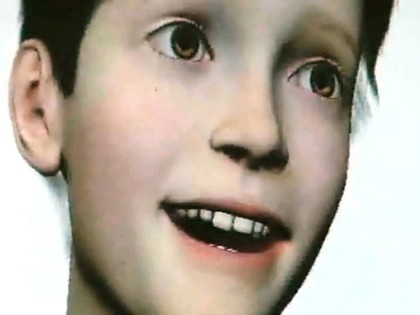

TR: Milo is quite interesting. It was clearly the 'talk' of E3. And it was almost sci-fi in terms of what it promised. Yet there were a few people who still said that they found it slightly creepy.

PM: When you present this to people then some people have that reaction. There was a high correlation between people whose favourite film was Terminator and the people who were creeped out by it!

It is so different. This is might whole point that I make. You don't meet computer game characters when you use a controller. You control computer game characters. And that is fundamental.

And yeah, I can sit back and watch someone playing and controlling a character and I think that's very entertaining and I've got completely used to it. But when I am actually sitting or standing or interacting with something who can obviously see me and obviously react to me, then that is meeting something – and it doesn't matter if it is a robot or a boy or a senior citizen or whatever – it is so totally new and different that you cannot help but make people feel slightly self-conscious.

And to a certain extent this proves that we are getting closer to this completely new territory.

What we found while making Milo, is that part of the skill of designing this whole new experience is in making people comfortable with the fact that they can be seen.

That things can recognise them and see them and have a relationship with them. And we've been talking about that for years and years, you know, emotional engagement in gaming... "are games art?"... "how can we make people cry and laugh?"

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

And then you begin to realise that this is a whole new area of interaction. Which really and truly has hardly even been dreamt of by science fiction writers. So I wasn't at all surprised by some of those reactions at E3. But it is down to our skill as designers to make sure that people don't feel creeped out by it.

TR: It reminded me of Arthur C Clarke's comment that "any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic."

PM: A lot of what we do is like magic. And I think of it like that. It is an experience, in which you sit back and you kind of know that this Milo character isn't really real. Just like you know that a magician's trick is a trick and not really magic. Derren Brown doesn't really predict the lottery numbers. But there is an enormous amount of entertainment in there.

Saying that, I do worry about 'over-promising' and firing people's imaginations up so much that their expectations are so unbelievably high that they think it is going to be like nothing they have ever experienced before or will ever experience again. So there is a careful play to be had here.

TR: Touching on a few other new gaming technologies that have generated a lot of interest in 2009 – what do you think about cloud gaming and about some of the latest 3D gaming technologies that are becoming available? And we have new touch-screen interfaces coming through now, what with the recent launch of Windows 7 on PC...

PM: When you think about it, 2009 has been a hell of a good year. If you take any one of the things that you have just mentioned now, it is actually hard to think about what is the most exciting thing out of all of them. They are all massively exciting.

The cloud is really important. When you actually start thinking about what we can do in the cloud, especially with artificial intelligence – which people really haven't talked a lot about.

Let me give you an example. It is something that we are kind of working on at the moment. One of the biggest problems in the world of computing is something called 'object recognition'. It is an incredibly hard problem.

Our human brains have evolved through millions of years to be able to recognise objects with no effort at all. And we would obviously love to be able to recognise objects with something like Natal. But it is such a tough problem to crack.

What with the cloud, what we can do is that when we release something that has object recognition in it - that is just the start of how that thing is able to recognise different objects – because the database of things that are being recognised being held in the cloud can continue to grow and improve. By the millions of people actually interacting with objects locally down here and sending the information back 'up' to the cloud, behind the scenes.

And from that some amazing and wonderful things will happen. The same with speech. The idea that the whole experience you have with the cloud doesn't need to be locked to the content on your DVD or content that you download. It is very much a living world that we can create now.

So there are huge differences with the cloud that complement the idea of creating and making games that go on an awful lot further. And then, in addition to all of that, as you mentioned, you have the latest developments in 3D and touchscreen tech which is really interesting. You can see the potential by just looking at the thousands of new things you can already do on the iPhone.

I think 2009 is a fantastically exciting year!

TR: What about storytelling? You made some interesting comment recently about how you were inspired by Dickens' "Penny Dreadfuls" when thinking about story in games.

PM: Yes. It is why I don't like demos. The first part of our game [Fable 3] is going to be free. And at the end of that first part you can choose to continue playing as normal, by buying the full game. Or, if you are still not quite sure, just buy the next episode.

And because it is constructed like that, by pure coincidence, the really big inspiration for Fable 3 was the world that Charles Dickens' had painted – the idea that there was a very two-faced rich versus the poor society... and the very visual ways in which he wrote about London, everything from Highgate Cemetery through to the workhouses.

It was fantastic inspiration and you can see how that will fit well with the Fable ethos. The moment you start to realise that all of Dickens' books were written to promote the sales of these 'Penny Dreadfuls' – where the idea was that he wrote a chapter, there was a cliff-hanger and people were literally raiding the ships where the magazines were printed on in their desperation to find out what happened next!

TR: Finally, why do you think the Golden Joystick awards are important for gaming? And what does it mean to you personally to be nominated?

PM: Well the obvious importance is that they are voted on by the public. This is not some elite panel of industry peers with a strange voting mechanic. It is actually gamers. So in that sense, it means a lot, particularly these days when user ratings are so, so critical. You buy iPhone games or Xbox Live Arcade games purely based on these types of ratings. So to be nominated for an award because people have bothered to vote for your title just makes you feel great.

To a great extent for a team like the Fable team – who have a real vision for what Fable is going to become and what its going to turn into – it is even more important. Just to keep them going through the quite hard and lengthy task of making a game. That coupled with the fact that the Golden Joysticks must surely have been one of the earliest awards ceremonies in gaming. I certainly remember going to one of the earliest cermonies at the Kensington Roof Gardens with Jonathan Ross – who was the first celebrity to put his name against the Joysticks. Or was it Bob Monkhouse? (Probably both of them!).

But that heritage is there. Which makes you even more proud to be nominated.

TR: Talking about heritage and the UK games industry – did you see BBC's Micro Men comedy recently? [About the history of the Sinclair Spectrum vs the BBC Micro]

PM: I haven't seen it yet, but I heard it was pretty good. And that Sir Clive Sinclair didn't come across too well. It's amazing that we are in an industry that can produce that amount of drama. I can assure you that it didn't feel like that amount of drama, back in those days! But now the dust has settled...

- 1

- 2

Current page: A strange little virtual boy called Milo

Prev Page How Natal takes us closer to Sinclair's dream