The taste of tech: can we control our gadgets with our tongues?

Tasting sounds and merging senses

Most of us take for granted how much we use our hands and fingers to control the technology, and therefore the world, around us. From switching on a TV, to communicating via WhatsApp to gaming, we use our digits and sense of touch to do all kinds of things without even really thinking about it.

But what about putting other parts of our bodies to work, like your mouth or your tongue? Or even – and bear with us here – your sense of taste?

These are some of the questions being asked by Francesca Perona, a designer, researcher and interface developer, who, along with her team, is interested in the potential of using our mouths to do far more than we might ever have believed possible.

Exploring the orifice

Commissioned by the Science Gallery London as part of its Mouthy: Into the Orifice season, Perona’s latest project is called Mouth CTRLer. It’s essentially a prosthetic device that you wear inside your mouth and use to interact with other technologies for communication, gaming and other applications.

To help us get our heads (or maybe our jaws) around the device, and what it can actually do for us, TechRadar asked Perona why she and her team decided to focus on the mouth in the first place.

“The mouth is a complex space, which literally interfaces the outside with the inside of our bodies,” she says. “It’s a channel to our more visceral, delicate, private self. The senses of smell, taste and touch converge in this space.”

And, as Perona explains, our mouths are a lot smarter than we might think. “We discovered through researching the functions of the mouth that the tongue can distinguish between more than 25 characteristics of food, from density to dryness to viscosity and much more,” she adds. “Basically, it’s a third hand.”

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

After much research, Perona and her team realised that the opportunities for combining the sensory capabilities of the mouth with prosthetics and tech could be huge.

Designing experiences for the mouth

We were keen to understand how researchers even began designing prosthetics in such a small – and relatively uncharted when it comes to tech – space. Perona tells us: “In terms of our thought process, in the initial stage of the project we sat down and mapped all the active and passive parts of the mouth. Teeth, lips, tongue, palate and so on. We then mapped potential ‘digital actions’ to those spaces and performed functions, such as navigate, press, click, open and close.”

The final piece of the jigsaw was figuring out which sensors would work best to bring about specific results – and putting these sensors into our mouths comes with a unique set of challenges. Perona adds: “Since it is an extremely wet space, sensors have to be well encapsulated, and the whole device needs to be produced in food-safe materials.

“Moreover, all mouths are extremely different. We explored and prototyped controllers that would fit in the palate, but we could not find a universal shape that would adapt to everyone, which is the reason why we then focused on sensors that could be actuated by teeth pressure.”

Tasting sound and hearing taste

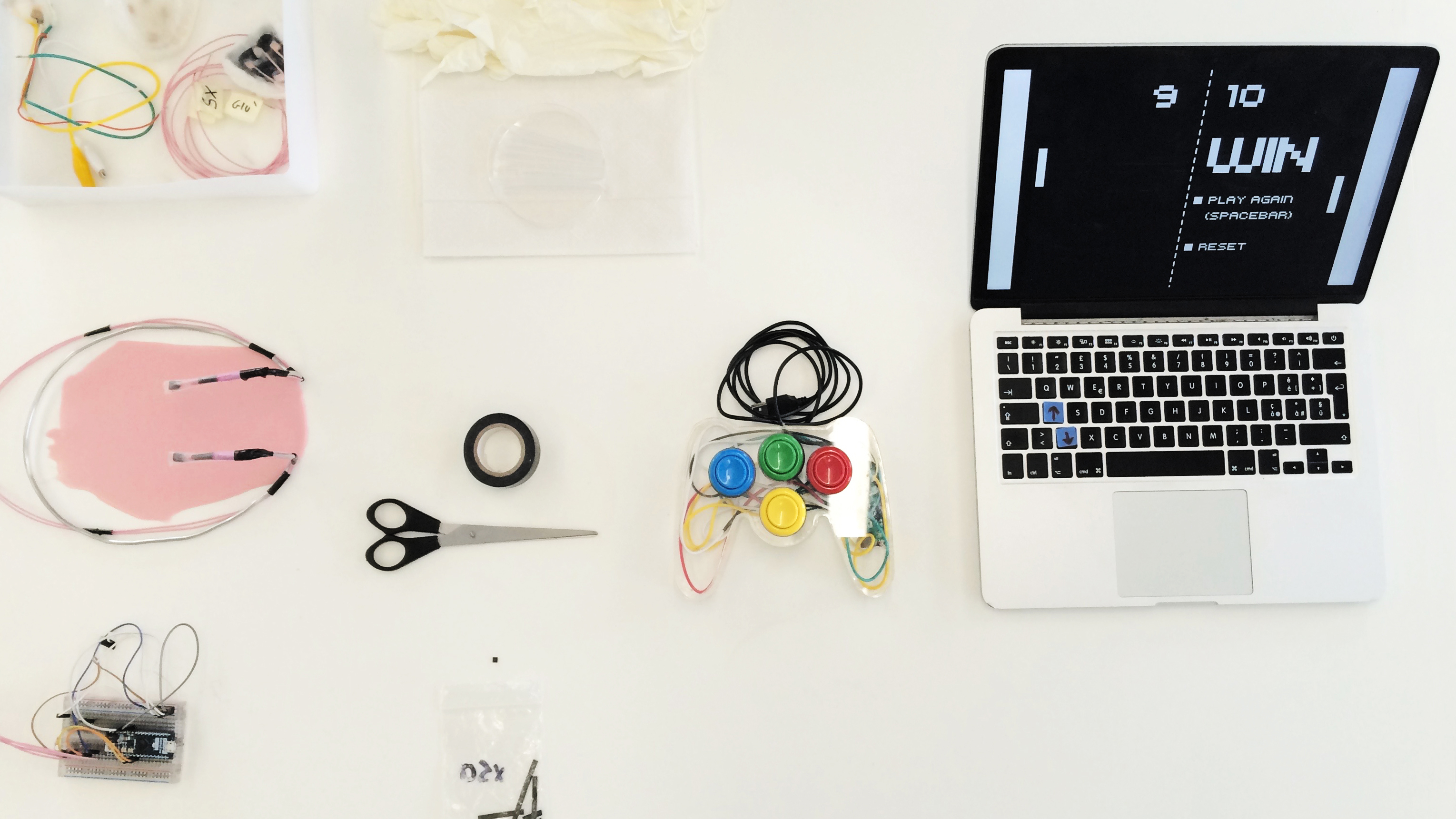

The Mouth CTRLer was designed to do all kinds of things – we watched people play a game of Pong at the demo, and the team has been working to blend our senses of taste and sound with a project called ‘The Taste of Music’.

Perona says cross-modalist scientists have been looking into the way our senses, particularly taste and sound, can impact one another for a long time. But her project aims to show how this can actually work in practice, and in a way that’s fun and accessible. The answer? Lollipops.

The team created lollipops that use pure tastants – substances that stimulate our sense of taste – in order to minimise smell and visual qualities. “The lollipop shape was designed to fit all kinds of mouths, and to plug directly to a bone conduction transducer,” Perona explains.

“The lollipop shape was also designed to help propagating sound vibrations from the bone conduction device to the widest possible surface of lips and teeth. By gently biting the lollipop or by resting the lips over it, participants can ‘hear’ sounds in their mouth while simultaneously experiencing the release of tastants.”

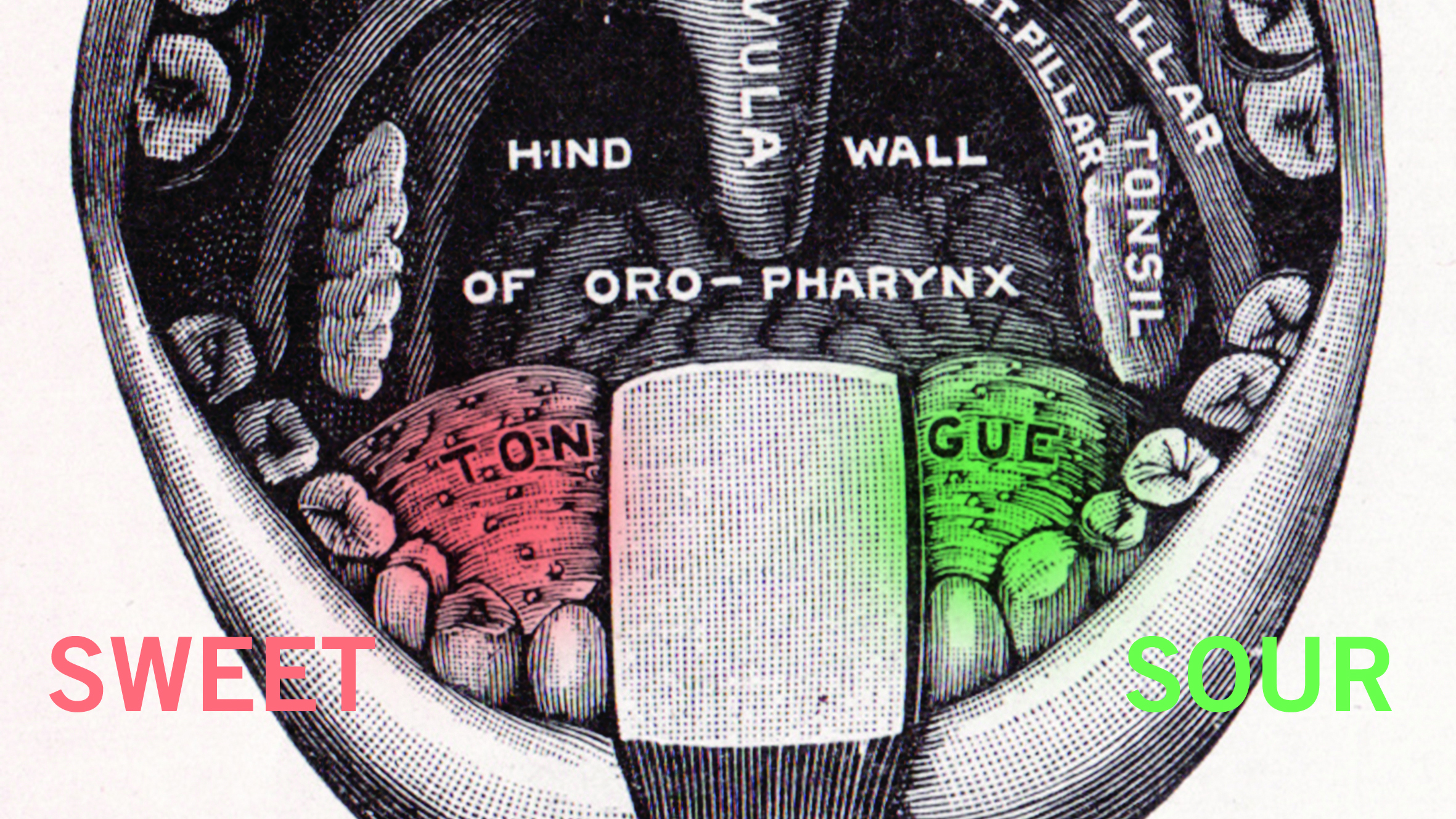

The team then involved Dr Shama Rahman, who specialises in the neuroscience of musical creativity (she’s also a professional actor and musician), to work with the five basic qualities of taste – sweet, sour, salty, bitter and umami – to develop compositions that enhance or modulate the perception of taste and sound.

Although it may sound like a highly esoteric area of focus, Perona explains that it’s becoming an important one for researchers like herself. “Technological advances in taste stimulation and multi-sensory mapping are fuelling a growing interest in the use of taste in interactive applications and experiences,” she says.

The role the mouth can play in assistive technologies

This kind of outside-the-box thinking has played an important role in the development of assistive technologies over the years. And it’s something that charities such as Able Gamers and Special Effect have been consulting on and lobbying for for years.

We asked Perona how she saw the Mouth CTRLer potentially aiding those with disabilities or physical impairments to better interact with technology in the future. She told us: “There is definitely a lot of scope in this area, and quite a lot of research happening already.

“The Quadstick, for example, integrates four ‘sip-n-puff’ switches, a lip position sensor, and a joystick. It is fully customisable, with 41 combinations (of different movements and sensors) available. However, we have read forums where users were complaining about the difficulty in customising the device, and other people were posting videos to help them configure them, which requires some bits of coding,” she explained.

The reason why using the mouth to design these kinds of assistive technologies is particularly appealing is because the tongue is a hugely important muscle.“The tongue is one of the strongest muscles in our body,” Perona says. “It’s the only one that is connected only on one side, and one of the few muscles that still works after spinal injuries.”

She believe it’s no surprise that other teams, like those behind the Tongue Drive, are making tech designed specially for the muscle. The Tongue Drive is a prosthetic device that uses magnets to attach to the tongue, allowing people to move their tongue and then translating that navigation information into both digital interfaces and physical spaces – navigate a wheelchair, for instance.

Perona says there’s still a lot of work to be done to develop better tech than what’s currently available. The Sip-n-puff system and the Quadstick are already commercially available, while the Tongue Drive system is still in the research phase.

“The commercially available ones are still quite bulky, and mainly external devices,” she adds. “Also, they are not really intuitive yet.”

The future of mouth tech

Having originally been inspired by the idea of creating better assistive technologies for those with disabilities and physical impairments, Perona now believes the potential for using our mouths to interact with technology, and each other, could have much wider applications.

To expand their thinking, she and her team convened workshops of people to think about the functions they perform with their mouths, and the cultural, social, aesthetic and emotional values of this orifice.

Perona adds: “Although disability-related applications were central to our discussions, ideas spanning sensory augmentation, personalised healthcare, enhanced learning, personal safety, training and long-distance communication were also explored.”

She believes there’s huge potential when it comes to healthcare, for using biosensors to monitor the wellbeing of an individual and provide feedback through sound. But there’s also scope to integrate mouth prosthetics into other new kinds of tech, like virtual reality.

She explained: “We also think that with the developments in VR, videogame experiences will become more ‘haptic’ for the general public too. There are already bodysuits that integrate vibration motors, to provide haptic feedback on different parts of the body.”

Whether you find Perona’s work fascinating or a little too esoteric, there’s no denying that everyone from big tech companies to assistive-tech startups to food researchers could benefit from thinking outside the box – and taking a closer look inside the mouth.

Becca is a contributor to TechRadar, a freelance journalist and author. She’s been writing about consumer tech and popular science for more than ten years, covering all kinds of topics, including why robots have eyes and whether we’ll experience the overview effect one day. She’s particularly interested in VR/AR, wearables, digital health, space tech and chatting to experts and academics about the future. She’s contributed to TechRadar, T3, Wired, New Scientist, The Guardian, Inverse and many more. Her first book, Screen Time, came out in January 2021 with Bonnier Books. She loves science-fiction, brutalist architecture, and spending too much time floating through space in virtual reality.