Why are mobile phone batteries still so crap?

Battery life hasn't kept pace with advances in mobile computing - but that could change soon

Mobile computing promises the world: web access, photos, music and maps, everywhere you go. And it can really deliver - for a while. But poor battery life means you'll probably soon run into problems, with some devices leaving you staring at a useless blank screen well before the end of the day.

There are some steps you can take to keep your system running longer, of course. The display is a major mobile phone energy hog, so reducing its brightness and timeout (the time a phone waits for input before turning the screen off) can make a significant difference.

Turning off GPS, Bluetooth and Wi-Fi when you don't need them also helps. This doesn't always have to be as absolute as it sounds. On the iPhone, for instance, you can disable Location Services on an app-by-app basis (Settings > Privacy > Location Services). On the software side, uninstalling apps you don't use will stop them draining your battery.

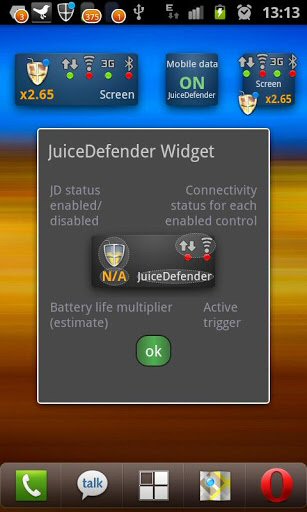

There are also tools you can use to extend your battery life. JuiceDefender, for instance, is an excellent Android app which automatically optimises power use.

All of these steps can bring minor improvements but none can make the fundamental difference we need. And you might be left wondering why battery life is still so poor, and what's being done to improve the situation.

Feature overload

Perhaps the main problem with battery life over the years is it really doesn't seem to have changed that much.

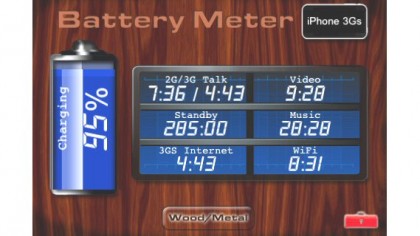

Take the iPhone, for example. The original device had a claimed talk time of 8 hours; the iPhone 5 is, well, the same. Internet use has nudged up from 6 hours to 8, and claimed standby time has actually dropped (225 hours vs 250).

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

There are very good reasons for this, though, and the main one is that you're now getting much more for your money.

A modern iPhone has gained 3G support, a vastly better screen (480 x 320 vs 1136 x 640), GPS, and the excellent iSight camera (8 megapixel vs 2). On top of that, there's the ability to run multiple apps in the background, each of which could drain your power further at any time. The fact that the latest iPhones can power all these extra functions while also fractionally extending overall battery life is a success story, not a failure.

This doesn't mean that the existing situation is good enough, of course. When, even now, many devices struggle to run for a full day without a recharge, then it's clear we need something better. Much better. And there are some promising technologies being developed right now which could point us in the right direction.

Extending Lithium-Ion

Today's lithium-ion batteries are straightforward and safe (well, mostly), but also have their limitations. In particular, the graphite anode they generally use has to be fairly large to store a reasonable amount of power, and so there's a great deal of research going on to find a less bulky replacement material.

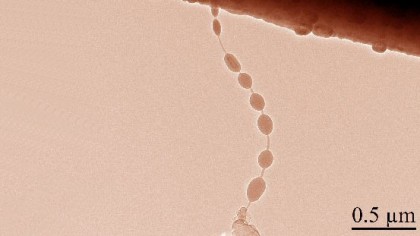

Silicon anodes, for instance, could help increase battery capacity by up to 10 times. But the big problem is that a simple flat layer of silicon absorbs so many ions that it actually grows significantly during charging, then shrinks during discharge, creating stresses which mean it destroys itself very quickly.

Recent research at the University of Maryland, however, found that growing tiny silicon beads on a carbon nanotube allowed them to expand during charging "like flexible balloons", without cracking. UMD Professor YuHuang Wang told us: "I believe that our finding is very significant. The Si bead on CNT structure is a breakthrough."

There is still much to do - the cathode and electrolyte also need to be able to handle this extra charge - but if Wang is right then this could help to deliver vastly improved power density, as well as batteries which can survive perhaps five times as many charge/ discharge cycles as they do today.

Mike is a lead security reviewer at Future, where he stress-tests VPNs, antivirus and more to find out which services are sure to keep you safe, and which are best avoided. Mike began his career as a lead software developer in the engineering world, where his creations were used by big-name companies from Rolls Royce to British Nuclear Fuels and British Aerospace. The early PC viruses caught Mike's attention, and he developed an interest in analyzing malware, and learning the low-level technical details of how Windows and network security work under the hood.