Linux audio explained

We dig into the centre of the Linux kernel to uncover why sound can be so... unsound

There's a problem with the state of Linux audio, and it's not that it doesn't always work. The issue is that it's overcomplicated.

This soon becomes evident if you sit down with a piece of paper and try to draw the relationships between the technologies involved with taking audio from a music file to your speakers: the diagram soon turns into a plate of knotted spaghetti.

This is a failure because there's nothing intrinsically more complicated about audio than any other technology. It enters your Linux box at one point and leaves at another. If we were drawing the OSI model used to describe the networking framework that connects your machine to every other machine on the network, we'd find clear strata, each with its own domain of processes and functionality.

There's very little overlap in layers, and you certainly don't find end-user processes in layer seven messing with the electrical impulses of the raw bitstreams in layer one.

Yet this is exactly what can happen with the Linux audio framework. There isn't even a clearly defined bottom level, with several audio technologies messing around with the kernel and your hardware independently.

Linux's audio architecture is more like the layers of the Earth's crust than the network model, with lower levels occasionally erupting on to the surface, causing confusion and distress, and upper layers moving to displace the underlying technology that was originally hidden.

The Open Sound Protocol, for example, used to be found at the kernel level talking to your hardware directly, but it's now a compatibility layer that sits on top of ALSA. ALSA itself has a kernel level stack and a higher API for programmers to use, mixing drivers and hardware properties with the ability to play back surround sound or an MP3 codec.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

When most distributions stick PulseAudio and GStreamer on top, you end up with a melting pot of instability with as much potential for destruction as the San Andreas fault.

ALSA

Inputs: PulseAudio, Jack, GStreamer, Xine, SDL, ESD

Outputs: Hardware, OSS

As Maria von Trapp said, "Let's start at the very beginning." When it comes to modern Linux audio, the beginning is the Advanced Linux Sound Architecture, or ALSA.

This connects to the Linux kernel and provides audio functionality to the rest of the system. But it's also far more ambitious than a normal kernel driver; it can mix, provide compatibility with other layers, create an API for programmers and work at such a low and stable latency that it can compete with the ASIO and CoreAudio equivalents on the Windows and OS X platforms.

ALSA was designed to replace OSS. However, OSS isn't really dead, thanks to a compatibility layer in ALSA designed to enable older, OSS-only applications to run. It's easiest to think of ALSA as the device driver layer of the Linux sound system.

Your audio hardware needs a corresponding kernel module, prefixed with snd_, and this needs to be loaded and running for anything to happen. This is why you need an ALSA kernel driver for any sound to be heard on your system, and why your laptop was mute for so long before someone thought of creating a driver for it.

Fortunately, most distros will configure your devices and modules automatically. ALSA is responsible for translating your audio hardware's capabilities into a software API that the rest of your system uses to manipulate sound. It was designed to tackle many of the shortcomings of OSS (and most other sound drivers at the time), the most notable of which was that only one application could access the hardware at a time.

This is why a software component in ALSA needs to manages audio requests and understand your hardware's capabilities. If you want to play a game while listening to music from Amarok, for example, ALSA needs to be able to take both of these audio streams and mix them together in software, or use a hardware mixer on your soundcard to the same effect.

ALSA can also manage up to eight audio devices and sometimes access the MIDI functionality on hardware, although this depends on the specifications of your hardware's audio driver and is becoming less important as computers get more powerful.

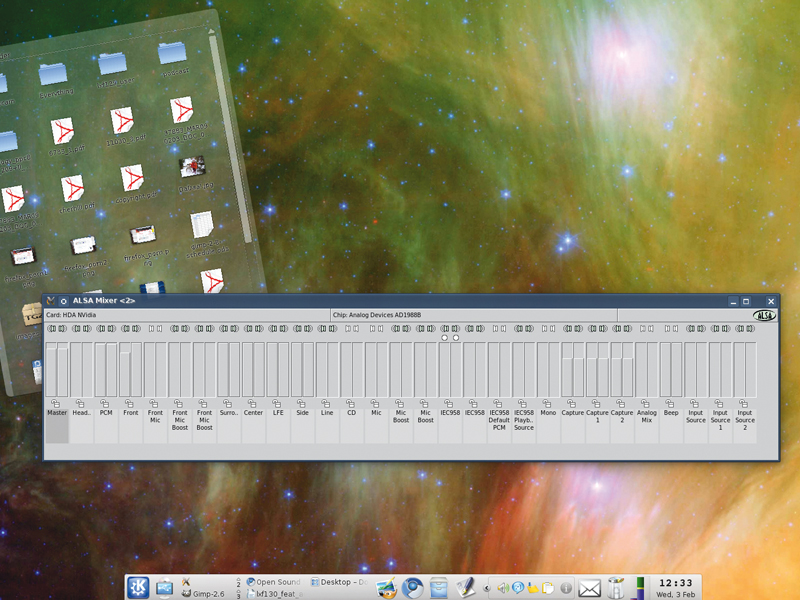

Where ALSA does differ from the typical kernel module/device driver is in the way it's partly user-configurable. This is where the complexity in Linux audio starts to appear, because you can alter almost anything about your ALSA configuration by creating your own config file – from how streams of audio are mixed together and which outputs they leave your system from, to the sample rate, bit-depth and real-time effects.

ALSA's relative transparency, efficiency and flexibility have helped to make it the standard for Linux audio, and the layer that almost every other audio framework has to go through in order to communicate with the audio hardware.

PulseAudio

Inputs: GStreamer, Xine, ALSA

Outputs: ALSA, Jack, ESD, OSS

If you're thinking that things are going to get easier with ALSA safely behind us, you're sadly mistaken. ALSA covers most of the nuts and bolts of getting audio into and out of your machine, but you must navigate another layer of complexity.

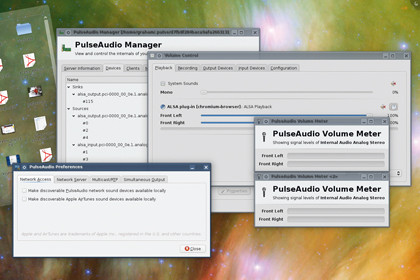

This is the domain of PulseAudio – an attempt to bridge the gap between hardware and software capabilities, local and remote machines, and the contents of audio streams. It does for networked audio what ALSA does for multiple soundcards, and has become something of a standard across many Linux distros because of its flexibility.

As with ALSA, this flexibility brings complexity, but the problem is compounded by PulseAudio because it's more user-facing. This means normal users are more likely to get tangled in its web. Most distros keep its configuration at arm's length; with the latest release of Ubuntu, for example, you might not even notice that PulseAudio is installed.

If you click on the mixer applet to adjust your soundcard's audio level, you get the ALSA panel, but what you're really seeing is ALSA going to PulseAudio, then back to ALSA – a virtual device.

At first glance, PulseAudio doesn't appear to add anything new to Linux audio, which is why it faces so much hostility. It doesn't simplify what we have already or make audio more robust, but it does add several important features. It's also the catch-all layer for Linux audio applications, regardless of their individual capabilities or the specification of your hardware.

If all applications used PulseAudio, things would be simple. Developers wouldn't need to worry about the complexities of other systems, because PulseAudio brings cross-platform compatibility. But this is one of the main reasons why there are so many other audio solutions.

Unlike ALSA, PulseAudio can run on multiple operating systems, including other POSIX platforms and Microsoft Windows. This means that if you build an application to use PulseAudio rather than ALSA, porting that application to a different platform should be easy.

But there's a symbiotic relationship between ALSA and PulseAudio because, on Linux systems, the latter needs the former to survive. PulseAudio configures itself as a virtual device connected to ALSA, like any other piece of hardware. This makes PulseAudio more like Jack, because it sits between ALSA and the desktop, piping data back and forth transparently.

It also has its own terminology. Sinks, for instance, are the final destination. These could be another machine on the network or the audio outputs on your soundcard courtesy of the virtual ALSA. The parts of PulseAudio that fill these sinks are called 'sources' – typically audio-generating applications on your system, audio inputs from your soundcard, or a network audio stream being sent from another PulseAudio machine.

Unlike Jack, applications aren't directly responsible for adding and removing sources, and you get a finer degree of control over each stream. Using the PulseAudio mixer, for example, you can adjust the relative volume of every application passing through PulseAudio, regardless of whether that application features its own slider or not. This is a great way of curtailing noisy websites.