Pretty much wherever you go online these days, you'll be using a web page with some level of intelligence behind it.

It may be something as simple as registering the fact that you're viewing the page, it may be tracking your likes and dislikes, or it may be providing an animation to make the experience of viewing the page better and more interactive.

No matter what's happening under the hood, it's most likely JavaScript code that's doing the work.

Project Mocha

Back in 1995, Netscape hired Brendan Eich, then at MicroUnity Systems Engineering, to help out with a new project called Mocha for the next version of the Netscape Navigator browser. Sun Microsystems had only recently launched Java applets – little programs that could run in a browser – but it needed some kind of 'glue code' for the browser to allow them to run.

Eich decided that a simple script language would be the answer. He opted for simplicity, because he realised that in all probability it wasn't going to be programmers creating a web page with Java applets, but web designers. Those designers would be using Java applets as black boxes that they would need to easily tie into the page.

He started work on a loosely typed interpreted language that he eventually called LiveScript. Since his intended users weren't programmers, he avoided standard development niceties like compilers and a formal object-oriented system, and made the language forgiving of minor mistakes that a more formal language would signal as errors and refuse to run.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

He also added hooks for code written in the language to interact with the page's HTML markup so that designers could manipulate forms, images and the like.

Just before Sun Microsystems and Netscape announced the new language in December 1995, it was renamed 'JavaScript' in a marketing attempt to more strongly emphasise that its purpose was to host Java applets. This was, to put it mildly, disastrous: JavaScript is not Java and, apart from some superficial syntactical resemblances, doesn't work like Java.

This naming decision has led to more problems for programmers than any other, because they have the expectation that the 'Java' in JavaScript means the Java they're used to using on the server side. The decision was also a disaster because web designers and programmers pretty much ignored Java applets, and instead used JavaScript to manipulate elements on the page (and it must be said, in the early days it was mostly image swapping: the rendering engine in the older browsers wasn't up to the task of rendering dynamic elements quickly).

Since there was no need for a compiler, coupled with the fact that you could copy and paste scripts from other sites into your own with pretty much no changes, and that testing a script was so easy (just load the page, essentially) meant that JavaScript took off to an astonishing degree.

'Real' programmers dismissed it as a toy at first – the ZX81 of the web – but it soon became ubiquitous, especially once Microsoft got in on the game.

Microsoft wades in

Microsoft's response was typical of the time: it released a scripting language based on Visual Basic called VBScript. It was strongly tied to Internet Explorer, and to Windows.

Since that wasn't to everyone's taste (Netscape Navigator was winning the browser wars at the time), Microsoft introduced its own version of JavaScript, called, for trademark reasons, JScript. JavaScript was a trademark of Sun Microsystems at the time, and is now owned by Oracle Corporation.

The problem was that Netscape ruled the browser space, and was notorious for introducing new features and options quickly and assertively. From that era we have JavaScript itself, as well as cookies, frames and poorly thoughtout HTML markup (who could forget the 'blink' attribute?).

Until IE3, Microsoft was playing catch-up in the JavaScript space. Eventually, with the push from IE3 users, Netscape and Sun were forced to seek the help of the European Computer Manufacturers Association (ECMA) to standardise the language, so web developers and designers would have some hope of writing code and running it without changes in the big two browsers. That led to the ECMAScript standard in 1997 (the third version of which, published in 1999, lasted for some 10 years). Yes, JavaScript is also known as ECMAScript.

Dynamic HTML

The next problem to afflict JavaScript and the browser space was Dynamic HTML (DHTML) and the Document Object Model, or DOM.

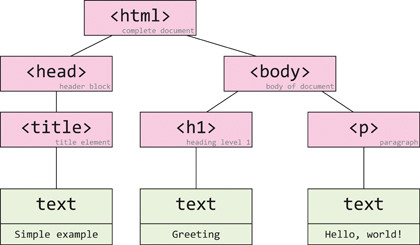

When Netscape and Microsoft released version 4.0 of their respective browsers, they added better access to the attributes and elements of a web page. This access was made through a library known as the DOM, a hierarchical tree data structure that represented the web page as a set of objects, where some are siblings to others and yet others are children (or alternately, parents) to other elements.

The figure above shows a simple HTML document represented as a DOM tree. In this, you can see that the 'head' and 'body' elements are siblings, whereas the 'h1' element is a child of 'body' (and therefore 'body' is the parent of 'h1'). The text nodes at the bottom are also part of the DOM, albeit not exactly as HTML elements.

Unfortunately, although the general ideas about hierarchy and the DOM element names were common across IE and Navigator, Microsoft and Netscape differed on how attributes of elements were to be accessed. Although everyone was now pretty much in agreement about how the scripting language worked, using it with DHTML proved to be a nightmare – one that's still with us today.

Anyone who has ever written cross-browser JavaScript code knows the weird byroads of incompatibility between the browsers' DOM. When Internet Explorer and Netscape 4.0 came out, you could soon get libraries that tried to make Netscape act like IE, and vice versa.

Other developers released libraries that encapsulated the commonality between the DOMs, though that generally meant forsaking some of the better parts of each DOM. This split between the DOMs led to sites that worked well in one browser and less so in the other.

The browser wars intensified as Microsoft, Netscape and others, together with the web standards body, the W3C, tried to standardise the DOMs. The process was lengthy, and, slowly but surely, Microsoft's Internet Explorer became the pre-eminent browser.

Since IE was delivered as part of Windows, it also led to the monopoly trials against Microsoft, and the rise of the Mozilla and other browsers like Firefox and Opera. JavaScript itself stayed pretty constant throughout this period of entrenchment and consolidation since the third edition of ECMAScript (which everyone was using) proved very stable.

There were high hopes for the fourth version of JavaScript, including a 'proper' object-oriented class model, but in the end the plans proved too ambitious and they were dropped for a simpler fifth edition – ECMAScript 5 – which is being integrated into the browsers' interpreters (Firefox 4 and IE9 both support ECMAScript 5).