Your intestines inspired this next-gen smartphone battery

It's villi effective

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Let me tell you a little bit about your intestines. You probably recall from school that there are two parts - a small and a large intestine. The large bit is basically poop storage. The small bit is more interesting - it's where most of the digestion and absorption of food takes place.

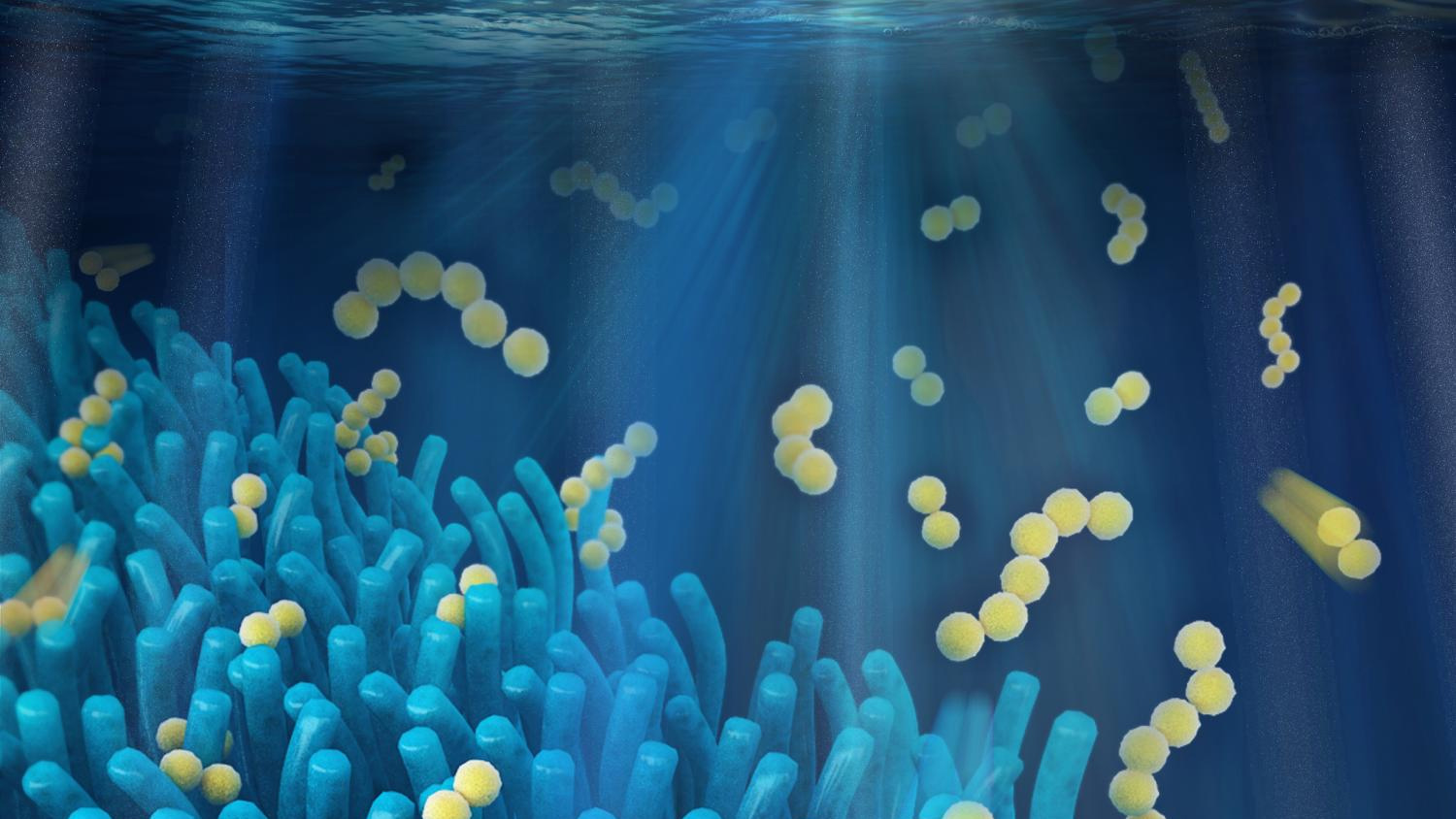

Key to that absorption process are the 'villi' that line the walls of the intestine. These finger-like protrusions, each about a millimetre long, massively increase the surface area of the intestine, making digestion way more efficient.

Now, a team of Chinese and British materials scientists have used exactly the same principle to make batteries way more efficient. They've developed a next-generation lithium-sulphur battery that has tiny nanoscale fingers coating its electrodes. As well as increasing the surface area, they also trap fragments of the electrode that break off, keeping them electrochemically accessible.

Through the bottleneck

"It's a tiny thing, this layer, but it's important," said study co-author Paul Coxon from Cambridge's Department of Materials Science and Metallurgy. "This gets us a long way through the bottleneck which is preventing the development of better batteries."

Teng Zhao, a PhD student from the Department of Materials Science & Metallurgy at the Beijing Institute of Technology, added: "By taking our inspiration from the natural world, we were able to come up with a solution that we hope will accelerate the development of next-generation batteries."

So far this is just a proof of principle, so it'll be a while until lithium-sulphur batteries become commercially available. There are other issues to solve before that happens too - lithium-sulphur batteries still don't last as long as lithium-ion batteries.

"This is a way of getting around one of those awkward little problems that affects all of us," said Coxon.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

"We're all tied in to our electronic devices - ultimately, we're just trying to make those devices work better, hopefully making our lives a little bit nicer."

The full details of the research were published in Advanced Functional Materials.