GAME and Britannica: eaten by the internet

Digital's great - when it doesn't leave anybody behind

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

On the face of it, beleaguered games chain GAME and the Encyclopaedia Britannica don't have much in common: one is a largely forgotten relic of a bygone era, and the other is a collection of books.

Ho ho!

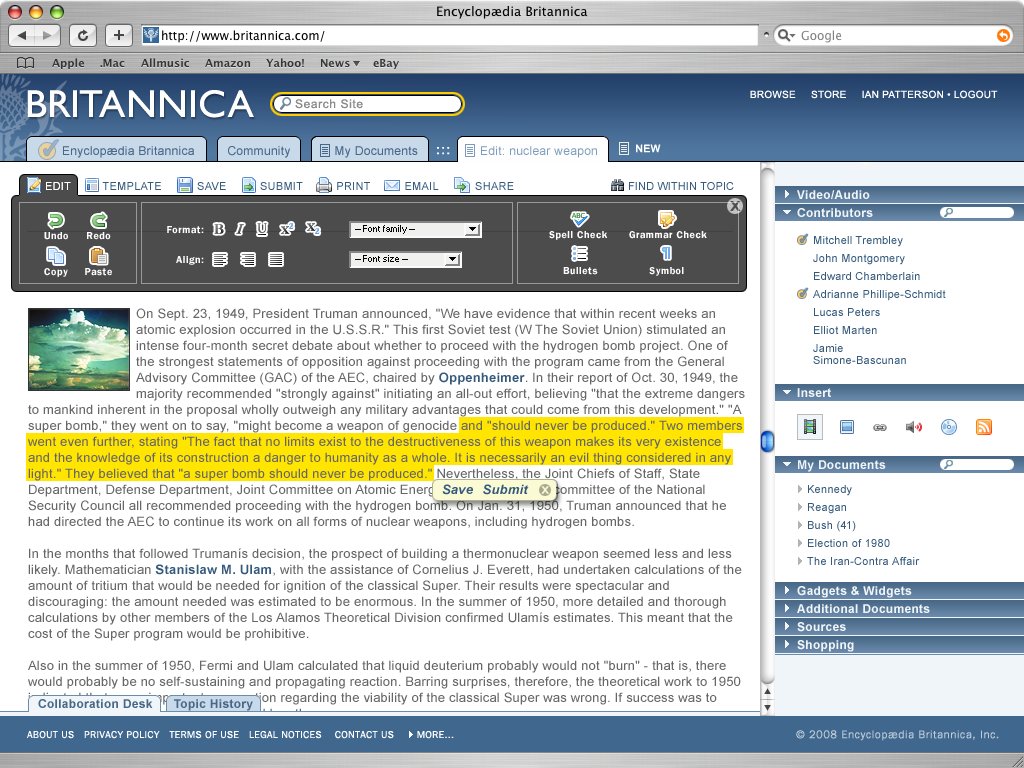

They're very different businesses, of course, but the games retailer and the encyclopaedia publisher have one very big thing in common: their core businesses have been eaten by the internet. GAME's desperately trying to find a buyer before it goes bust, and the Encyclopaedia Britannica is stopping the presses after 244 years.

Article continues belowThe internet isn't the only perpetrator here -- GAME has suffered at the hands of supermarket loss leaders and publishers' use of one-time codes to try and kill its preowned section too; encyclopaedias have been under attack since the CD-ROM era -- but it's the main one.

Online shops with razor-thin margins, VAT-free importers and the rise of digital delivery have wiped out GAME's health bar -- I don't know about you, but whenever I've wandered into GAME I've taken one look at the prices, wandered back out and ordered online instead - and it's hard to justify the cost of a bunch of Britannicas when Wikipedia is free and significantly more up to date.

The internet has found a better way to do things.

Hasn't it?

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

We're all in this together

I worry that as we become more digital, we're creating sticks we'll be beaten with. If we're not careful, the rush to digital can trample on consumer rights and damage the most disadvantaged people in society.

When I buy a book, a real one, it's mine. I can set it on fire, give it away, lend it, sell it on, donate it to a charity shop, whatever I feel like. With some limited exceptions I can't do that with digital. I can't even be sure that I'll own it for the lifetime of my device: in many cases developers or publishers can issue updates that remove features from the product I've already paid for.

Digital-only also restricts lending: in many cases libraries can lend books but not ebooks, DVDs but not downloads, CDs but not MP3s. Some retailers currently rent out game DVDs. Digital-only kills that too.

Moving everything online is fine and dandy if you've got a smartphone and a data plan, or an iPad or PC with a broadband connection and money in the bank for a Netflix account or a Spotify subscription or a bunch of Kindle ebooks, but millions of people don't.

Many people can't even get on to the free sites such as Wikipedia: according to the UK government, ten million UK adults have never used the internet - that's a fifth of the population - and the less money you have, the less likely you are to be online. The unemployed and families with young children account for more than half of the people on the wrong side of the digital divide, and the numbers are significantly worse in rural areas than urban ones.

In an ideal world libraries would enable anybody to get online and get onto Wikipedia, but our world is currently a world of swingeing cuts and library closures.

I owe a big chunk of my education, most of my career and my love of Talk Talk to my local library, and I worry that the more digital we become the less people will be able to do what I did, to access content without having to pay through the nose for it.

The internet has found a better way to do things for most people, but not all people. Let's make sure that as we go all-digital, we don't leave anybody behind.

Contributor

Writer, broadcaster, musician and kitchen gadget obsessive Carrie Marshall has been writing about tech since 1998, contributing sage advice and odd opinions to all kinds of magazines and websites as well as writing more than twenty books. Her latest, a love letter to music titled Small Town Joy, is on sale now. She is the singer in spectacularly obscure Glaswegian rock band Unquiet Mind.