Sleep tracking might be one of your smartwatch’s most important features

I found out the tiring way

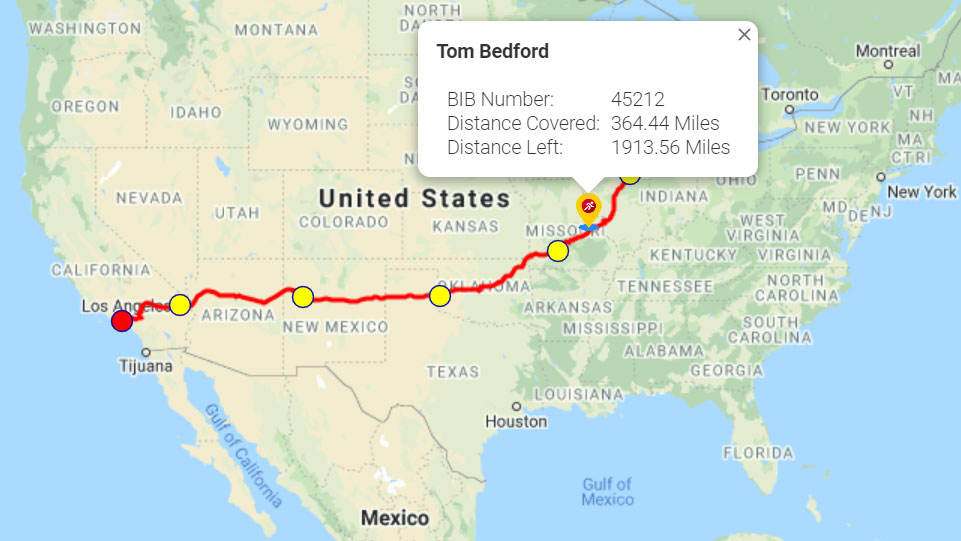

As part of my ongoing running challenge to run or walk nearly 2,300 miles in two years, I’m having to use smartwatches, fitness trackers and running watches to account for all the journeys I make. Short run? Track it. Walk to the store? Slap that band on. Walk to the toilet? Let’s get those steps in.

Column number: 7

Date written: 27/05/21

Days in: 87

Current location: Stanton, MO

Distance traveled: 364.44 miles

Distance left: 1913.56 miles

Current tracker: Polar Vantage M2

The one area I haven’t been monitoring as much with these devices is my sleep. That’s in part because big watches can be annoying to wear at night; partly because some trackers can be poor at accurately judging when you go to bed; and also because I just didn’t know what to do with the sleep data collected.

I’ve come to regret this decision, though – because it turns out that sleep is even more important for working out than I’d thought (of course I know sleep is important, but I just didn’t know how important it is).

After wearing the Polar Vantage M2 for a few weeks, using it to track runs, long-distance walks and my sleep, I spoke to psychiatrist and sleep medicine specialist Dr Meeta Singh, who analyzed my sleep data. Using her expertise in the field, she pointed out some key learnings from my data that I wish I’d known sooner.

A parliament of night owls

I’m a night owl: someone who’s most productive late into the night, and struggles to rise early as a result. Having to work 9-5pm doesn’t change this, even though 7am wake-ups are the norm; it just means I get fewer hours of sleep. I thought forcefully changing my circadian rhythm to fit the normal work day was my only recourse – but it turns out, this isn’t the case.

In fact, one of Dr Singh’s first bits of advice was to obey your body clock: “Being a night owl or a morning person, it is something that’s intrinsic. When [sleep specialists] are talking to people, we want them to try to sleep according to their biological clock.”

It isn’t only sleeping hours that are affected by your circadian rhythm, though; your peak exercise time is too. “The time of the day that you’re best at exercising really depends on your chronotype,” Dr Singh told me. “There is a certain time during the day where we’re biologically wired to be at our best. For somebody who goes to bed at 11pm and wakes at 7am, that's between 4pm and 7pm in the evening.”

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

I’ve always known I’m an evening person, but using the timing stats from the Polar watch helped me to work out exactly how much of a night owl I am, and as a result figure out my optimal running times. It turns out, just before dinner is best for me – which is perfect timing to earn that pizza.

Overcompensation

My sleep data also revealed to Dr Singh that I was chronically sleep-deprived. I was getting an insufficient amount of sleep in the five days through the week and then compensating for that at the weekend, playing catch-up and sleeping extra.

But it turns out that this is a big ‘no-no’ – according to Dr Singh, it’s “really bad for you”. Oops.

So why is this? Surely it could only result in me feeling a little more tired? Much worse, it seems: “Doing this on a regular basis can cause cardiovascular or cardiometabolic side effects. The glucose metabolism gets impaired, so it makes it more difficult for people to lose weight.”

“If you're chronically getting maybe only five or six hours of sleep a night, then it affects the way your body utilizes glucose… you become hungrier, and you crave fatty carbohydrate-rich food.” Maybe that pizza dinner isn’t such a good idea, after all.

The adverse health effect isn’t the only issue, though. Dr Singh mentioned something that will be familiar to those who have worked nights. “It’s called social jetlag”, she told us. “If, on a regular basis, I went to bed at 10pm and woke at 5am, but then on the weekend I go to bed at 2am and sleep until 10am or noon, it would almost be like every weekend, I had decided to go to California, which is three hours ahead.”

Regular social jetlag can apparently exacerbate the cardio metabolic side effects of chronic sleep deprivation, making you tired, and stopping your fat-burning workouts from being as effective. And if you’ve ever tried functioning while jetlagged, you’ll know it can affect your performance.

So what’s the remedy? Quit working, so you don’t have to wake up at the crack of dawn? Actually, the solution isn’t all that dramatic.

“I would say that if you could get a little bit more sleep, even on the days you're working, that would be great. Instead of waking up at 6.30am, you could sleep until about 7am.” Dr Singh told us.

And while that may sound like a pipe dream, it is actually achievable. By showering, preparing my overnight oats for breakfast, and pre-deciding on which of my identical-looking shirts I’d wear the night before, I have managed to get my ‘bed-to-door’ routine down to just 10 minutes.

There’s something else worth trying, too. Something that I previously thought was an exclusive activity for babies, cats sitting in the sun, and students who haven’t yet discovered Red Bull: napping. “Because of the busy lives that most people lead, sometimes the only way to accommodate that extra half-an-hour or so [of sleep] is via a nap,” Dr Singh explained.

There are some caveats, though. “You don't want to nap too close to your bedtime, since that will make it difficult for you to fall asleep at bedtime. Those people who have difficulty sleeping shouldn’t take a nap, either, because that would further worsen their ability to sleep at night.”

Is there a ‘best’ time to take a nap? “There is usually a dip in the mid-afternoon for most people, when they feel less alert. That’s the time to take a nap.” Maybe your experience may vary, but when Dr Singh said this I immediately knew when that ‘dip’ was for me. “It's related to your circadian rhythm. And so that's a good time to take a nap.”

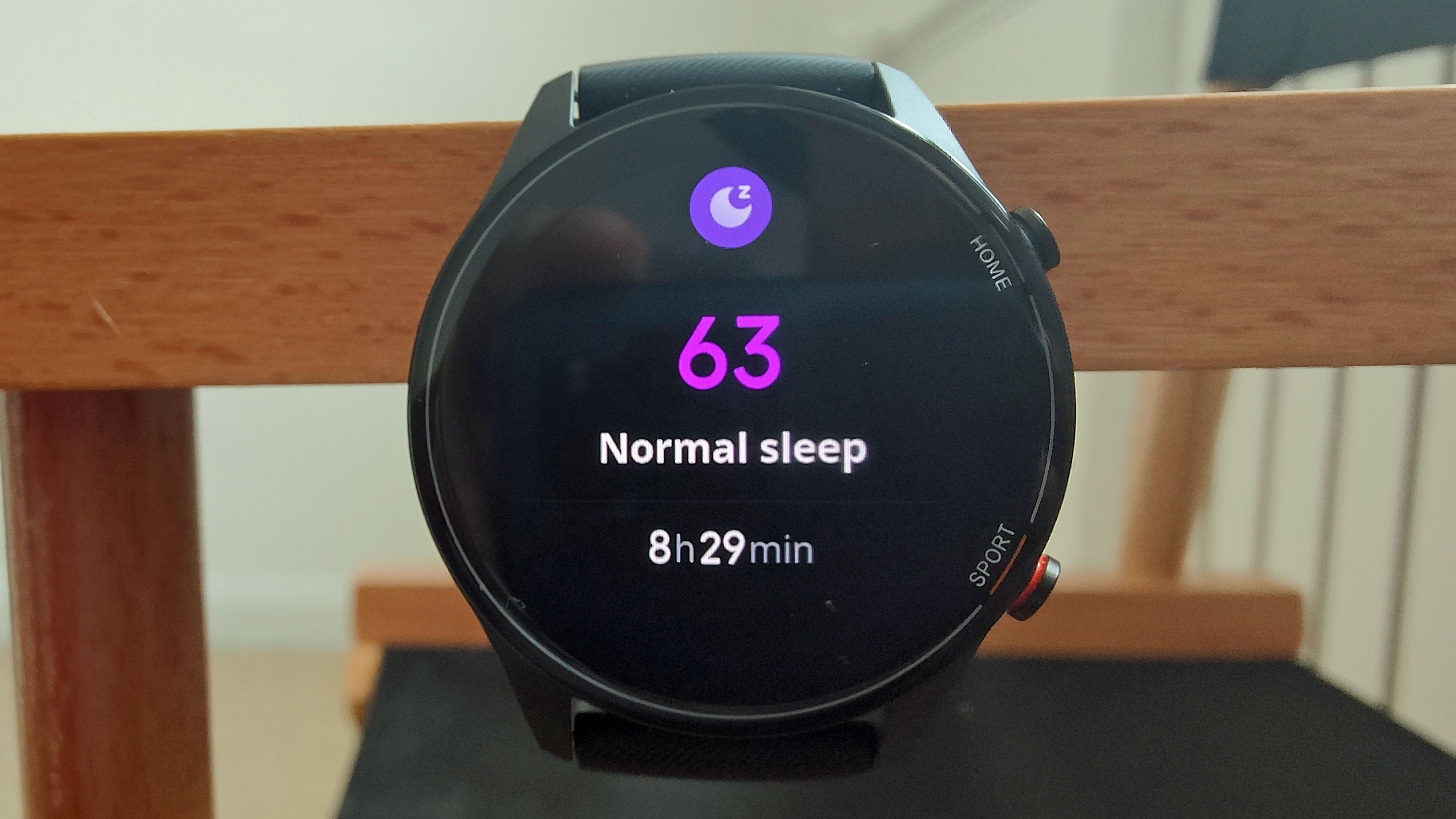

The recommended daily amount of sleep is seven to nine hours, and as my fitness tracker noted, I was usually falling short. Perhaps by amending my wake-up routine or finding an extra half-an-hour, I could bump that number up.

Sleep data, run better

Throughout our conversation, Dr Singh mentioned a number of reasons that sleeping is vital for fitness fans in particular. “You need sleep for muscle recovery to happen; your muscles actually store up to 70% of the glucose that's in your bloodstream, and most of the storage function happens while you're resting.”

Your sleep doesn’t just affect your muscles: “Your heart, your lungs, your digestive system; everything has a nightly reset, and that happens while you're asleep.” In fact, “there isn’t a single aspect of any human performance that isn’t affected by not getting enough sleep.”

Some fitness trackers let you view a breakdown of the type of sleep you get and, according to Dr Singh, deep sleep is key: “Deep sleep is what is most restorative; that's the time muscle recovery tends to happen.”

In fact, sometimes sleep is more important than exercise. “People will ask me, ‘should I wake up early to exercise or should I get an extra half-an-hour of sleep?’. Of course I'm biased,

but I’d say that it's more important to make sure you're well-rested, because sleep is biological and it’s a matter of balance”.

Off the track(er)s

Fitness trackers and their sleep-monitoring functions can be super-useful for understanding your habits, then – and they obviously were in my case – but it helps not to overthink the stats.

“If you’re able to look at a [fitness tracker] without becoming anxious about the data, then it’s a win-win situation. You get some information from it, which you can use to make some changes in your life.

“But there is actually a disorder, where some people become anxious about their sleep. When they use any sort of monitor to keep an eye on their sleep, it becomes worse.” This disorder is called Orthosomnia, and a piece in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine describes how people can self-diagnose sleep problems based on feedback from gadgets, regardless of the accuracy of the data.

There’s a delicate balance, then, between using fitness trackers to improve your fitness, and incorrectly analyzing the data they collate to potentially harmful effect.

As such, it’s best to use this data as something to consider, rather than solid life guidance. If you use a fitness tracker then you might notice you’re waking earlier than you want, so could find a way to rise later. Or maybe you’ll spot that, like me, your sleep patterns are too irregular. But if you think you could have an actual sleep disorder or condition, it’s best to see a doctor.

I’m going to continue using fitness trackers to monitor my sleep – now that I know what I should be looking for. I think it will be easier to spot any changes, and therefore optimize my sleep to fit my workouts. But this might not be the route for everyone.

Through my conversation with Dr Meeta Singh, we discussed a few other aspects of sleep that didn’t fit so easily into this article. If you’re interested, the key points are listed below:

- Regular exercise can help boost your deep sleep timings - but overtraining can make sleep much harder.

- Natural light is vital for circadian rhythm - "light as an alertness pill" according to Dr Singh, making it important for natural wake-ups.

- Optimizing sleep is about keeping to your circadian rhythm, getting a good quality of sleep, and retaining a consistent quantity of sleep.

- You shouldn't play video games, or any other activities where you're actively participating (like social media) just before bed.

Tom Bedford is a freelance contributor covering tech, entertainment and gaming. Beyond TechRadar, he has bylines on sites including GamesRadar, Digital Trends, WhattoWatch and BGR. From 2019 to 2022 he was on the TechRadar team as the staff writer and then deputy editor for the mobile team.