Why it's time to trade your fitness tracker for a smart ring

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

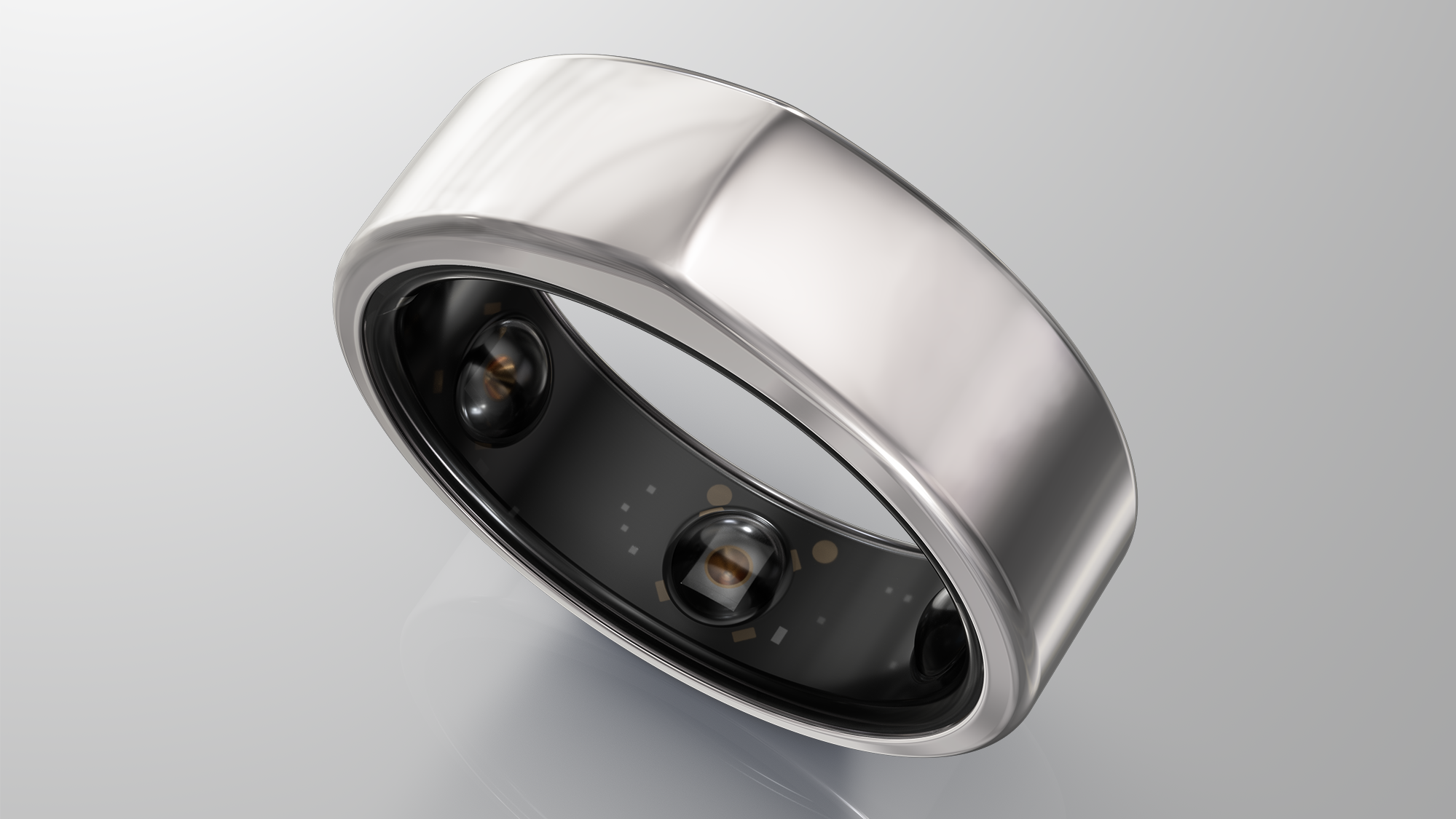

Smart rings are a convenient, unobtrusive way to track all kinds of health metrics, including heart rate, temperature and activity levels – so why are so many of us still sticking with chunky smartwatches and cumbersome fitness trackers? To find out, TechRadar spoke to Harpreet Singh Rai, CEO of Oura Health, which has sold more than 500,000 rings to date and recently took part in a study to detect signs of Covid-19 several days before a person tests positive for the virus.

Oura Health began in Finland in 2014, and announced its first-generation smart ring on Kickstarter at the end of 2015. Rai wasn’t one of the founders – in fact, he was working on Wall Street at the time – but a chance meeting in a grocery store led to him taking the helm.

Rai studied mechanical engineering at university, working on projects including an accelerometer and a neural probe, but after graduating he moved into investment banking to help clear his student debt. The decision was good for his financial situation, but terrible for his health. “I gained 50lb in my first year,” he says, “and honestly, the hours were brutal. For the first time in my life, I wasn’t sleeping well and I couldn’t fall asleep.”

It took such a toll that he eventually switched to a different role in investment banking, which gave him a much better work life balance. The change was profound. He soon lost the excess weight, and started learning more about his own body – particularly how it was affected by sleep.

“I started reading some of the most fascinating things, like how all your muscle repair actually happens in your sleep, and all your memories are formed,” he says. “Literally, in REM sleep, your brain replays memories from the previous day at three times the speed to help you learn. And there are even things like natural killer T-cells that fight off cancer in your sleep.”

I started reading some of the most fascinating things, like how all your muscle repair actually happens in your sleep, and all your memories are formed

Harpreet Singh Rai

It was something he’d never paid attention to before, and that newfound curiosity, combined with his background in mechanical engineering, really piqued his interest in the Oura ring. “I tried the product, and it was the first one where I thought the data actually felt right,” he says.

He’d only been wearing the ring for two or three weeks, when he happened to bump into one of the company’s Finnish co-founders in a New York branch of Whole Foods. “He was like, ‘That’s the first Oura ring I’ve seen outside the office!’” Rai recalls.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

The two spent most of the following day together, discussing the company’s future. “They were trying to raise money, and having a bit of a hard time. I’d spent 10 years on Wall Street, and I’d worked at a hedge fund investing in companies – mainly public companies, but some privates in the tech space too, and I decided to invest and help them raise their series A. I joined the board, and then about three months after, they asked me to join full-time as president to help grow the business.”

Shortly after, the board and founders asked him to take charge as CEO – and things have accelerated from there.

Finger on the pulse

So why choose a ring rather than a watch? As Rai explains, heart rate data from the finger tends to be more accurate than that from the wrist. “Blood vessels on the finger are closer to the surface, and the pulse signal is about 100 times stronger than on the wrist – and that’s probably the part that most customers don’t know,” Rai says.

“That’s the same reason why every heart rate monitor and SPO2 in hospitals measures from the finger. And those are wired. It’s not a power thing – it’s just the quality of that signal. The signal-to-noise ratio.”

Measuring from the finger also means you can measure heart rate continuously without using a lot of power. “A lot of wrist-based wearables don’t [measure continuously] – they sample, then sampling turns off and they extrapolate the data,” Rai says. “You know, if an Apple Watch ran in workout mode sampling at 60Hz, it would probably die in about three to six hours. We sample at 250Hz continuously all through the night, and we do that for almost six nights in a row without the battery having issues.

“I think the quality of the data manifests itself in the research,” he says, “We just published a sleep staging paper for our new algorithm developments that shows we’re more accurate than any other wearable out there, including our previous generations, and including Fitbit and Garmin.”

Blood vessels on the finger are closer to the surface, and the pulse signal is about 100 times stronger than on the wrist

Harpreet Singh Rai

Oura has partnered with the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) to put that data to use in a study to determine whether data from a wearable sensor can show that a person is developing Covid-19, even if their symptoms are subtle.

“The data that UCSF published looks astounding – for 70% of the people analyzed who were positive, you could see significant changes in their data three days in advance. For the remaining cohort, 14% was basically one to two days in advance, and 10% the same day.”

Building a smart ring

So if a smart ring gives superior data, why aren’t there more of them? According to Rai, there are three main reasons – one of which is simply the difficulty of getting components that will fit. You can’t simply buy sensor modules from a supplier as you can if you’re building a watch.

“If you’re Fitbit, Apple, Samsung, Garmin or Whoop, you typically end up buying those modules for certain features on the hardware side,” he says. “So if you’re going to make a heart rate sensor, you talk to Xiaomi, maybe Maxim on the component side. They normally have modules established, with firmware already working.”

You have to make your own manufacturing process – it’s not like there are ready-made manufacturing processes off the shelf

Harpreet Singh Rai

Rai already knew all these companies, and had invested in similar ones during his time at the hedge fund. He therefore also knew their limitations.

“When you buy modules from these companies, they often come in building blocks of a certain size and power consumption, and if you want to do anything outside of that – something that needs, let’s say, smaller space – you’ll have to assemble the components one by one, and make your own modules to bring those features. And that takes a lot of time. That’s the challenge.”

The second difficulty is the manufacturing side. “There’s more space for a watch,” Rai says. “You know, you can get screwdrivers and things like that, and they’re really tiny, but it’s much harder on a ring. You have to make your own manufacturing process – it’s not like there are ready-made manufacturing processes off the shelf.”

Finally, Rai says, there’s the difficulty of persuading customers that a ring has more value than a watch – it’s not just a different form factor.

“I think some of the earlier smart ring companies didn’t necessarily have as much of a product-market fit,” he explains. “I think Ringly was one pretty early on, and I think that the idea of just phone notifications would have probably done way better. I think it was just a little too early for its time. I think Motiv was another player that just went out of business, but I think they had a lot of manufacturing issues that led to poor signal quality and high return rates.”

There as also several smart ring brands working on NFC for payments, but again Rai says there are hurdles when it comes to adoption. “It’s been slower than they want, but in Europe it’s nice to see that actually accelerating much better. In Japan too, but I think a single-purpose hardware device is probably a smaller audience right now. Hopefully things can grow in the future, though.”

It’s still early days for smart rings, but there’s a chance that the competition could soon heat up. Earlier this year, Fitbit registered a patent suggesting that it may be developing “a ring for optically measuring biometric data” – specifically focusing on blood oxygen levels. That certainly doesn’t guarantee that a Fitbit Ring is in the horizon, but it would make a lot of sense if the company wants to improve the quality of its data.

It will have a tough job catching up with Oura though. We’re currently testing the ring ourselves, and early signs are very promising – the overall experience is polished, and the data is impressive – particularly when it comes to measuring sleep stages throughout the night. We’ll bring you a full review very soon.

- We've tested and ranked the best running watches

Cat is TechRadar's Homes Editor specializing in kitchen appliances and smart home technology. She's been a tech journalist for 15 years, having worked on print magazines including PC Plus and PC Format, and is a Speciality Coffee Association (SCA) certified barista. Whether you want to invest in some smart lights or pick up a new espresso machine, she's the right person to help.