How to take night sky images with your phone

From star-trails to Moon close-ups, smartphone astrophotography is getting easier

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Main image: The Moon, photographed with an iPhone. Credit: Jamie Carter

We all know about the amazing quality of today’s smartphone cameras, but how often have you pointed one at the night sky? Smartphone astrophotography is not going to match those images from the Hubble Space Telescope, or from a DSLR camera attached to a telescope on an equatorial mount, which follows stars as they appear to move.

However, what you can capture with your phone – from close-ups of planets and the craters and mountain range of the Moon to timelapses and star-trails – will astound you. Get ready, Instagram, for some astronomically good phone images.

Manual control apps

The sensitivity of the sensor in your smartphone's camera may be set, but how you control it is not. While the native camera app on your phone is pretty restrictive, there are a raft of apps that give you manual control of ISO, exposure, shutter speed, and even allow you to capture in raw rather than JPEG.

That's important because raw images contain a lot more data than a JPEG, which is heavily compressed, so can withstand post-processing in Photoshop or similar photo-editing software.

The app of choice with smartphone astrophotographers is NightCap Camera for the iPhone, which has various preset modes, but also allows manual control of ISO, shutter speed, white balance, focus and digital noise reduction.

"Many astrophotographers will take multiple images and then 'stack' the images using a desktop computer, but NightCap Camera stacks images in the iPhone or iPad," says amateur astronomer Mike Weasner at Cassiopeia Observatory in Arizona , who was the first person to do astrophotography with an iPhone back in 2007.

"This stacking capability allows for imaging brighter deep sky objects, and it also lets NightCap Camera create star trail images in the device, or capture long exposures showing the motion of bright satellites like the International Space Station."

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

How to photograph stars, satellites and the Northern Lights

Wide-field astrophotography is not typically a strength of smartphone cameras, but things are changing. As well as having more sensitive sensors, phones like the iPhone 7 and Samsung Galaxy S7 and S8 have excellent exposure control.

However, you do need to use them with a manual control app, as well as put them on a tripod using a bracket – although at a pinch you can steady your phone by leaning it against something, even a rock.

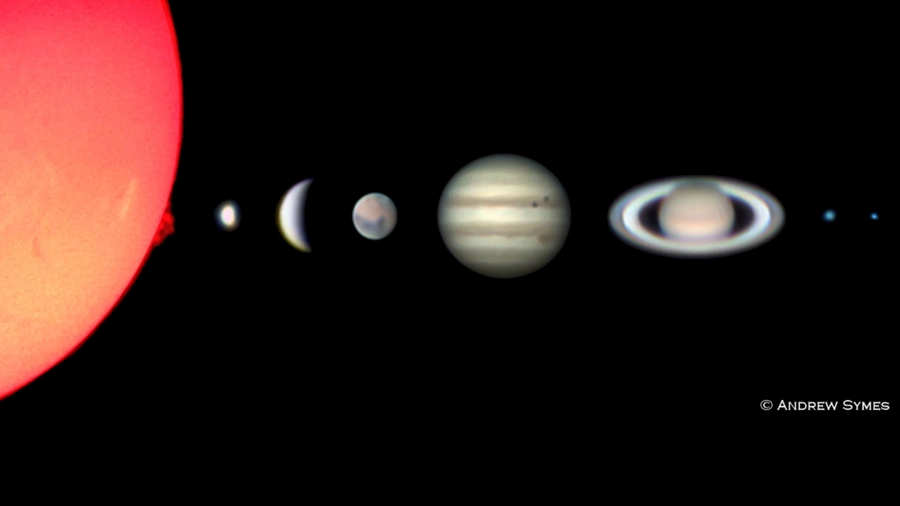

"On their own, smartphones will often only pick up the very brightest stars and planets, and the photos aren't very spectacular," says astrophotography expert Andrew Symes. "But with a low-light app you can capture some nice images of constellations and the Milky Way along with objects in the foreground – I've also caught the Northern Lights this way."

Any app with manual control will allow you to capture satellites, the brightest and easiest of which is the International Space Station (ISS), for which NightCap Camera has a dedicated mode. Check SpotTheStation for the next flyover where you live.

"For the Milky Way, constellations, or Zodiacal Light use Long Exposure and Light Boost mode in NightCap Camera," says Weasner, advising experimenting with ISO, shutter speed and exposure.

How to create a star-trail image

A good star-trail can be mesmerising, and the circular patterns you can produce will give a new perspective on the rhythms of the night sky. Although some will gaze at such photos with awe, producing an image that shows the exact movement of the night sky over an hour or so is a relatively simple technique. The beauty of NightCap Camera is that's it has a built-in Star Trails mode, so you don't have to do much apart from orientation and timing.

To maximize the number of stars in the final image, wait for a night with no moon (the week before new Moon is good), choose somewhere dark and away from artificial light, put your fully-charged phone on a tripod. Point it north if you want the classic circles (if you go south, you'll get curves). Take the brightness right down, and press go. Wait for an hour; NightCap Camera will automatically produce a star-trail.

How to get a close-up of the Moon

For this one you'll need any telescope, and ideally a smartphone adaptor like the Orion Steadypix Universal or Levenhuk. An adaptor is optional; it is possible to take a thoroughly decent photo of the Moon just by holding it up to the eyepiece of a telescope. However, it is a bit tricky to align it consistently, and an adaptor makes it much, much easier.

"Make sure that your focus is perfect," says Symes, who uses a Celestron NexStar 8SE telescope. "I often use the digital zoom on my phone to zoom in on a prominent crater or feature and check the focus, make sure it's in perfect focus, and then zoom back out because you don't want to use much digital zoom in your telescopic photos."

Crop the images later, and if you want to get closer, use a higher-powered eyepiece. If you're using a refractor or Cassegrain telescope, you'll also need to flip the final image.

You also don't want to overexpose the many very bright white areas on the Moon. "Use the phone camera's exposure adjustment tool to dim the moon to the point where the brightest areas are properly exposed." Advises Symes. "I find that with the latest iPhone models it helps to adjust the brightness while zoomed in on the moon using digital zoom. I zoom in so that the moon fills more than the entire view, set and hold the brightness, and then zoom out."

The advantage of the Orion Steadypix Universal is that it attaches to both an eyepiece or a tripod, so you can use it for wide-field astrophotography as well as close-ups. You can also make your own.

How to get a close-up of a planet

Getting an image of the Moon through a static telescope is possible, but how quickly our satellite appears to move (thanks to Earth's rotation) will shock you; it just won't stay still. Ditto the planets.

“iPhones have such good brightness controls that I can brighten and dim the planets using just the phone's built-in tools," says Symes, though he advises that for some Android phones a polarizing moon filter might be needed to dim the moon and bright planets enough to expose them properly.

So if a computerised telescope, which tracks objects as the Earth rotates, is handy for photos of the bright moon, it's essential for the much dimmer planets. "It allows you to keep the object centered," explains Symes. "It can often be difficult and time consuming to initially get your object in the frame of the phone camera, so once it's there it really helps if you don't have to keep adjusting your telescope to reposition the object."

As well as encouraging smartphone astrophotographers to experiment with fisheye and wide angle clip-on lenses for constellations and star-trails, Weasner has some ingenious advice to keep the phone steady: use the volume buttons on a pair of earbuds as a remote shutter release.

A tripod – even a table top one – will also make your life a lot easier. “They will get you started with star-trails, constellations, satellites, planet configurations, and more," says Weasner.

If you want to photograph the Moon, phases of Venus, moons of Jupiter, Saturn's ring, and brighter deep sky objects, you'll still need a telescope, but smartphones are at last becoming a cost-effective way to experiment with astro-photography.

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),