The many faces of in-game advertising

How in-game ads can help pay for titles big and small

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The downside, of course, has been that the products have often been completely unrelated to the game, which has sometimes prompted a gloriously ranty horde of gamers to headbut down the door of irrelevant ad peddlers in response – or prompted a Penny Arcade comic strip.

See your ad here

Recent IGA trends have led gamers into a tight corner. On the one hand these adverts rarely take anything away from gameplay; an IGA often will show up as a billboard on the side of the highway or a relatively innocuous poster and only exist in-game as a petulant eyesore on the worst of days.

On the other hand launching ads that are consistently suitable for any game and genre is highly unlikely, and combining a game with an ill-fitting ad provides a bucket of cold water for any gamer seeking an escape from everyday reality through a game world.

A billboard flashing an ad for Motorola might fit in the backdrop of Times Square in True Crime: New York City, but we're not always so lucky. In 2005, SWAT 4, a tactical shooter not known for wising cracks, included a promotional campaign for the Canadian animated sci-fi comedy Tripping the Rift for US players. While the game tried to convey the tense experience of leading a five-man team around a serial killer's lair and coping with realistic firearm protocols, ad posters for a comedy show peppered the walls. Surreal maybe, but also a great way to shatter the atmosphere.

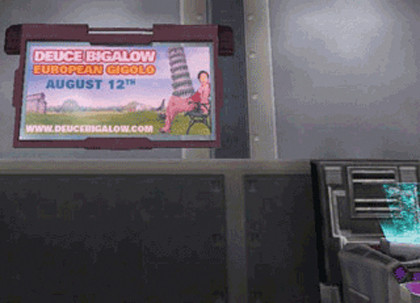

Similarly, the MMOFPS Planetside, a game that took place one thousand years in the future featured posters promoting the premiere of Rob Schneider film Deuce Bigalow: European Gigolo.

Ads saved the videogame

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

However IGAs don't always hinder a game, in fact they help pay for the big titles. With the current cost of cranking out good AAA games, ad revenues at least offer the possibility of offsetting initial costs. Costs so high you'll feel a bit ill.

Gone are the days when a developer could turn out an MMO for eight million dollars. The current poster boy, Modern Warfare 2 cost between $40 to $50m to produce and even after 12 million copies sold, the publisher wasn't guaranteed a profit. It has subsequently bounced back with a hefty $381m net profit for the first quarter for this year, but from a commercial standpoint, IGAs offer publishers a much needed cheque after years of production costs.

And likewise, the gaming industry has grown as a leading player in commercial entertainment. The work put into shoehorning brand names into games is evidence of the mainstream's acceptance of games as both a steadfast medium and competitor, as opposed to a simple novelty.

And with TV demographics drifting since the early noughties, advertising agencies all want to reach the 18 to 34 year-old, couch-bound male demographic. As we've seen with the internet, television and radio before that, games are being shaped into commercial spaces, although it's not necessarily a commercial takeover.

And that's because from a creative standpoint, the revenue taken from adverts can help to recover some of the costs put into creating games, giving development teams more leeway to take risks for the sake of experimentation and new innovative gameplay.

But more than that, it can offer a very helpful hand to smaller independent companies. It's a land of pirates out there in the commercial market, pirates and cheapskates. With the ease of downloading it can be hard for some to find the incentive to cough up the 30 or so quid for a top-class AAA game. But for an independent company already trying to avoid sickeningly high developing costs, pirated downloads can be crippling.

Traditionally this has been dealt with through dear ol' DRM, that's used various means, some more controversial (*cough* Ubi *cough*) than others to impose limitations on how game content can be accessed.

Security guru, Bruce Schneier once described attempts to make files uncopyable "like trying to make water less wet". Maybe then, ad revenues are the lesser evil that could be the far less tedious and cumbersome alternative for gamers and a way for developers to off-set their losses?

Thirty years in and IGAs are still a work in progress, but in their current form they have the potential to offer us DRM-free games – as well as a burger and a side of fries.