First China, then Israel – now India is landing on the moon in 2019

Chandrayaan-2 mission signals Asia’s space ambitions.

The race for the moon is back on – and Asia has an early lead. Already this year China has landed Chang’e-4 on the far side of the moon, while Israel’s Beresheet is currently in lunar orbit and scheduled to put a lander on its near side on April 11. Now India is on the cusp of making a daring attempt to land on the near side of the moon close to its south pole.

What is Chandrayaan-2?

Chandrayaan-2 (chandrayaan means ‘moon vehicle' in Sanskrit) is an ambitious mission from the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) that involves an orbiter and a lander, the latter of which will unleash a lunar rover called 'Vikram’ to take measurements and map the surface.

Like Israel’s Beresheet, Chandrayaan-2 will put a NASA-owned laser reflector on the moon’s surface, which will help NASA take precise measurements of the distance to the moon.

When, where and how will Chandrayaan-2 launch?

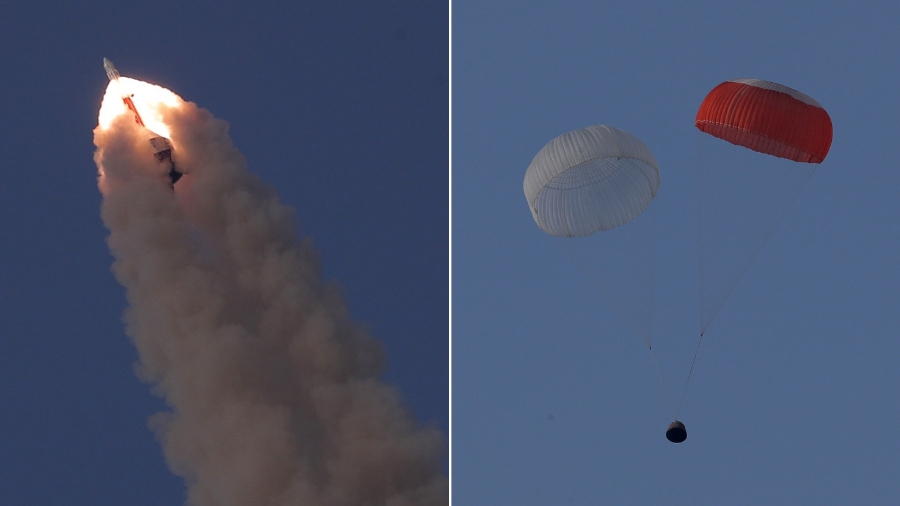

Although it's been beset with delays, the launch window is now open for Chandrayaan-2 to blast-off from the Satish Dhawan Space Center in Sriharikota, Andhra Pradesh. Chandrayaan-2 will be carried into space by an Indian-made three-stage GSLV Mark III rocket worth about $60 million (roughly £45 million, AU$85 million).

"I've been told that the mission will launch in the next few months, though there is no firm date," says Pallava Bagla, Science Editor at New Delhi Television and correspondent at Science. "But the scientific payloads are ready."

What caused Chandrayaan-2’s delays?

"It was delayed a few years ago because it was to be a joint Indo-Russian mission, but the Russian lander has issues, so India decided to make the lander on its own," says Bagla.

After a couple of failures of its GSLV Mark II rocket, India also changed its mind on using it for such a high profile mission as Chandrayaan-2, so it had to design a modified GSLV Mark III rocket.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

"It’s the heaviest lift vehicles India has, so the mission became a little heavier," says Bagla. That extra bulk allowance meant the lander was reconfigured, and the mission delayed.

Possible target dates for the lander to reach the lunar surface are the full moons on April 19, May 18 or June 17, though India is due to hold elections (for a staggering 900 million voters) between April and the end of May, which could cause more delays.

How long will the lander and rover last?

"The mission life is one lunar day," says Bagla of the solar-powered lander and rover. "It has to land just when the moon is full and it will last 14 days so that it can use the entire solar cycle to do its work.”

That may not seem like long, but remember that during Apollo 11 – the 50th anniversary of which is coming up on 20 July – the first astronauts on the moon were only there for two and a half hours. Besides, Chandrayaan-2 is way more ambitious than India's first moon orbiter over a decade ago, Chandrayaan-1 – and that brought big, big news.

What did Chandrayaan-1 do?

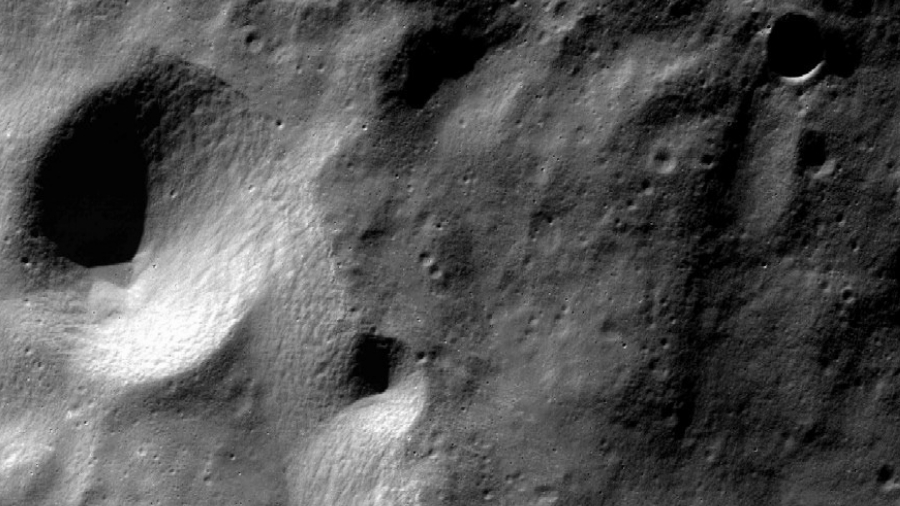

Chandrayaan-2 is taking place a decade after the $54 million (about £41 million, AU$76 million) Chandrayaan-1, India’s first mission to the moon. Launched in 2008, Chandrayaan-1 was a spectacular success because its data revealed water ice on the moon in permanently shadowed craters near the north and south poles. However, contact with the orbiter was lost less than halfway through its intended two-year mission.

Still, its discovery of water on the moon explains why Chandrayaan-2 is headed for the south pole; its science takes up where Chandrayaan-1 left off, yet is much more comprehensive.

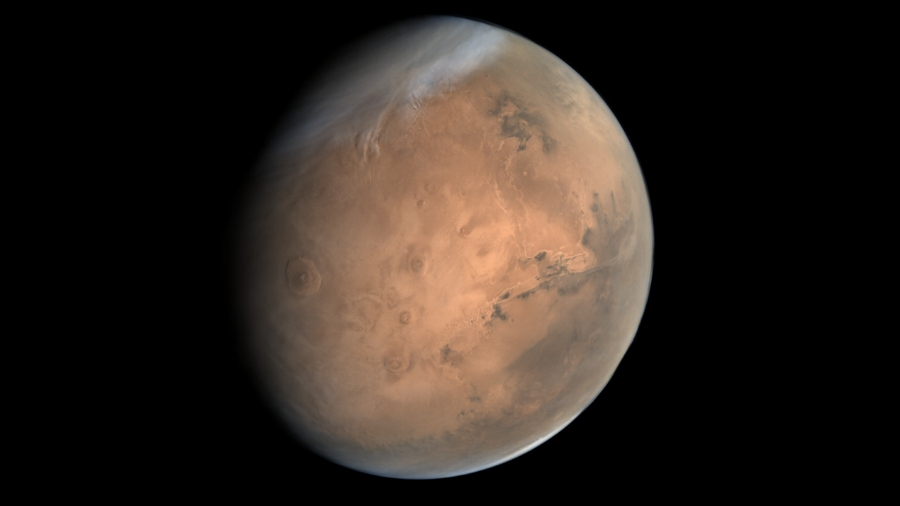

India also successfully undertook its Mars Orbiter Mission in 2014, from where it sent back some spectacular images of Mars.

Where will Chandrayaan-2 land?

The moon’s south pole, or close to it. That’s crucial because water ice at the moon’s poles could prove a critical resource for any future crewed missions to the moon or a moon-base. However, this is a risky mission.

"Everyone understands that for a complex mission like this there are chances of failure," says Bagla. The separation of the lander from the orbiter, as well as the lunar landing itself (during which the lander will free-fall the last few meters onto the lunar surface), will be completely automated.

"You have to hit the bullseye in one go once you decide to land because if you're not able to fire your retro rockets and land with the minimum of energy, you have a failure," says Bagla.

What tech is on the Chandrayaan-2 rover?

A six-wheeled, completely solar-powered rover weighing just 25kg, Vikram will have aboard it 13 separate scientific instruments to help gather data on the as-yet-unexplored region the moon. During the 14 Earth days (one lunar day) it will study the solar wind, ultraviolet radiation, radar-map the lunar surface, and precisely locate molecular water.

However, after its short mission, Vikram and the lander will be plunged into a 14-day darkness – and die. This is a short mission that must land just as the moon reaches its full phase.

What will India do next?

ISRO has ambitious plans for a robotic mission to Venus, and also intends to return to Mars – in a mission likely to feature a lander and rover – but ISRO's priority after Chandrayaan-2 is a $1.4 billion (about £1 billion, AU$2 billion) Gaganyaan ('orbital vehicle') mission to put three Indian 'gaganauts' (including at least one female gaganaut) into orbit for the first time. Indian prime minister Narendra Modi has given ISRO a target of August 15 2022, when India will celebrate the 75th anniversary of its independence.

Whether Chandrayaan-2 is a success or not remains to be seen, but the presence of both China and India on the moon will send a powerful message about the world’s rising political and scientific powers.

Welcome to TechRadar's Space Week – a celebration of space exploration, throughout our solar system and beyond. Visit our Space Week hub to stay up to date with all the latest news and features.

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),