Dolby Atmos for the People: R.E.M. on the lost art of listening

Revisiting a classic album with all-new audio tech

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When was the last time you listened to an album? Or even a song?

You may say last night, this morning, five minutes ago. But I mean really listened - free from other distractions, letting the sounds envelope you, phone switched off, Twitter thumbs disengaged, no YouTube comments to rail against, the stream of endless notifications turned off.

Even the services that ostensibly serve our love of music are guilty of attempting to pull us away from it – the Spotify share buttons, Google Play Music’s insistence that you try its premium playback tier.

Instant gratification and connected distractions have diminished the personal, deliberate gesture of playing music.

Putting on an album used to be something of a ritual, a meditative, reflective act, at its zenith with the lush cover folds of a vinyl record, but still a precise act with any other physical media, be that the cassette or the CD.

From scanning the shelves at the record store to filing your purchase on your shelves at home, to picking out the record best suited to the feeling of the moment, popping it into your stereo and letting the next hour or so carry you away on a sonic cruise, it was a journey of sorts.

Digital music has had its benefits – not least the somewhat eerie prescience of an AI uncovering and recommending a little-known artist that perfectly suits your tastes – but the instant gratification and connected distractions have diminished that personal, deliberate gesture.

Shiny Dolby People

I’m as much a victim of / participant in the modern musical tech cycle, but found my own little oasis last week, listening to one of my all-time favorite albums in the dark screening room of Dolby’s headquarters in Soho, London.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

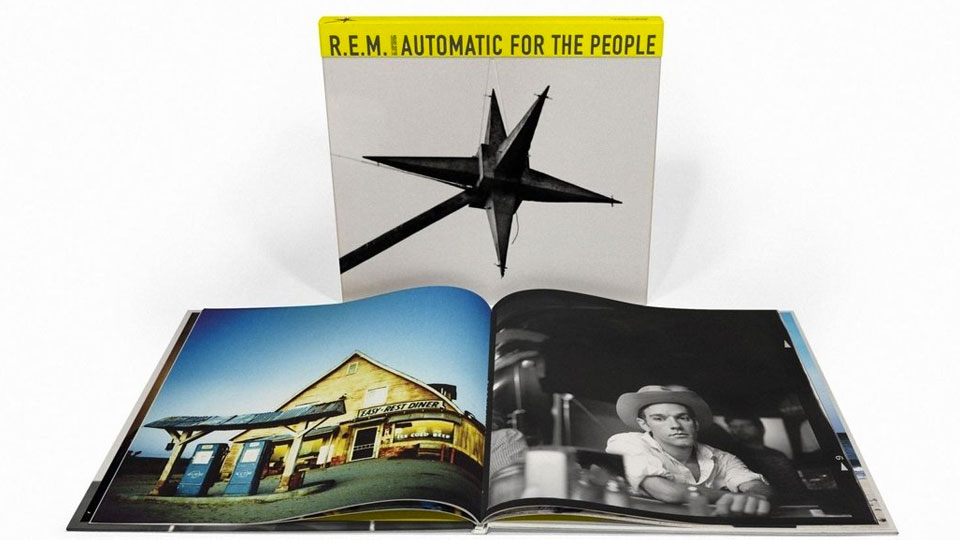

The irony of course is that this epiphany-filled afternoon was enabled by the march of technological progress itself. Dolby Atmos is perhaps the most advanced sound system in the world, and alt-rock pioneers R.E.M. have harnessed it to breathe new life into their classic 1992 album ‘Automatic for the People’ for its 25th anniversary re-release. I was invited to listen to the astounding new mix.

Dolby Atmos is an object-based audio system that’s increasingly used in cinemas around the world, and is finally trickling down into home cinema set-ups, too.

It uses overhead speakers (or, in a home set-up, speakers pointed at a ceiling to bounce sounds to your ears), allowing individual sounds (or in the case of music, instrument tracks) to move around you to give a sense of 3D space superior to a 5.1 or 7.1 surround setup. Atmos is also available through software processing, allowing it to be simulated for headphones too.

It’s impressive tech, but even R.E.M. frontman Michael Stipe had to be convinced of its appeal initially.

“At first I was like, whatever, it’s a thing. I listen to music on my iPhone and my computer, I don’t have a stereo system [...] So I’m not a stereo-sonic audio guy,” said Stipe at a talk after the listening session, which TechRadar attended.

“But it was breathtaking to hear. My best friend was in the room when we heard it and he had to leave afterwards, he was so moved by the experience. Not only of how it sounded (the guys worked really hard to put it together and to mix it and I don’t want to diminish that), but he was ecstatic, he didn't stay around after to have a drink after the listening party, he couldn’t.”

Nightswimming deserves a quiet mind

The lush, layered sounds of Automatic for the People, all strings and organs and mandolins, are the perfect invitation for an Atmos mix – and it’s a very different experience to listening to a film’s audio, for those that may have previously experienced Atmos in this capacity.

Rather than the sense of being at the heart of the action, it’s a more painterly effect. Highlighting a little-noticed percussive section here, or long-buried string arrangement there, a vocal harmony can hide behind the listener, or an anthemic chorus punch from all around.

To not be on your phone for 45 minutes, to not be looking at something else, or have that distraction. That’s quite rare. That in itself is quite a beautiful experience.

Michael Stipe, R.E.M.

To counter my earlier point in fact, Atmos too adds a storytelling element to the sounds – the movement of an instrument suggesting a different emotional intensity than a stereo mix allows for.

In the case of R.E.M’s ‘Automatic for the People’, the energetic stabs of strings on ‘The Sidewinder Sleeps Tonite’ adds a joyous jauntiness through its movement, while the poetry of ‘Nightswimming’ is laid bare and open as its lyric, the delicate arrangement giving the listener literal space to observe from.

But, if not more profound than the new mix but certainly elevated by it, was the mono-sensory joy of giving my attention so wholly over to just the sound. In the dark of the cinema, I could engage my thoughts entirely with the audio, the way Stipe’s vocal played against and weaved through the pull of a mandolin string, the meaning of his words a mirror to the soundscapes created. This was giving my ears over to music for music’s sake, not as an aside or accompaniment to some other act, and something that is increasingly difficult to find time for today.

Speaking of an earlier listening session, Stipe recalled how his "friend Jane Pratt was there and she said, ‘I don’t know if you were watching me while you were listening, but we were sat there in the dark, and it was just music.’

“In 2017, it’s so rare to focus in on just one single sense, and allow one thing to come in. To not be on your phone for 45 minutes, to not be looking at something else, or have that distraction. That’s quite rare. That in itself is quite a beautiful experience.”

The great beyond

‘Automatic…’ is one of only a handful of musical pieces adapted for Dolby Atmos, joining The Beatles ‘Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band on the format. The strength of the mix would make you hope more artists and albums will follow it.

“I don’t know that you’d want to use technology just for the sake of using it,” counters R.E.M. bassist Mike Mills.

“Certainly this record stands up well to it. I’m trying to picture our album Monster in Atmos… it may work! But it’s actually fascinating to see – when you mix it, you have a 3D representation of the room on the screen. You can literally move the little dots around that represent the tracks and see where they go and where you want to put them.

“It’s a limited thing, because how many people have [a Dolby Atmos-capable sound system] in their house? Not many. I have 5.1 surround sound, which this would work for on a scaled down basis. Since there are a lot of audiophiles who really enjoy music I don’t see why we wouldn’t [try more records with an Atmos mix]. If the record company pays for it!”

As Mills notes, the Dolby Atmos owners’ club is a relatively exclusive one at the moment – it’s a pricey, audiophile grade investment, one that would require some remodelling to your ceiling in order to take advantage of its superior overhead set-up.

But if it can inspire a return to the ritual of record playing, that lost art of just listening, to quote R.E.M itself, “sweetness follows.”

Gerald is Editor-in-Chief of Shortlist.com. Previously he was the Executive Editor for TechRadar, taking care of the site's home cinema, gaming, smart home, entertainment and audio output. He loves gaming, but don't expect him to play with you unless your console is hooked up to a 4K HDR screen and a 7.1 surround system. Before TechRadar, Gerald was Editor of Gizmodo UK. He was also the EIC of iMore.com, and is the author of 'Get Technology: Upgrade Your Future', published by Aurum Press.