Could you create the next hit iPhone game?

From drawing board to App Store in 7 steps

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There are more than two million mobile apps available on the App Store right now (and that number is rising rapidly as you’re reading this), according to Statista – and a whopping 23% of those are games.

Not only are gaming apps the most popular category, they're also the apps people spend the most time using. Figures suggest users spend an average of 7.55 minutes in a gaming app session, which (unsurprisingly) makes it the most profitable app category out there.

But while big-name games and world-renowned studios are responsible for lots of these sales, like Sniper Hitman, Monopoly and Minecraft, there have been some breakthrough hits from indie developers and smaller companies over the years – Monument Valley and Alto's Adventure are two that spring to mind – that prove you don’t necessarily need a wealth of experience, a big budget or a global team to make your iPhone game a reality – just a good idea and truckloads of enthusiasm.

TechRadar talked to some inspiring people working in the iPhone gaming industry who took small ideas and turned them into big successes. So read on to learn a bit more about how an iPhone game is created, and how you can turn your dreams into downloads.

Step 1: get all your ducks in a row

Chris Thomas is the developer behind Fuzzy Face Studio and created the virtual pet game Tweechi, bringing together a team of four enthusiasts who built the game during evenings and weekends while also holding down full time jobs.

We chatted to Thomas about how Fuzzy Face came about. “The team is comprised of friends I went to college with or who I worked with in previous jobs, all of whom I knew were passionate about games and brought specific skills to the table – art, animation and coding knowledge,” he explained.

“We had weekly video calls to revise new builds and effectively designed as we went. It was a fun and valuable experience.”

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

His top tips for getting started once you’ve assembled your team are to stick to a plan – which he admits can be challenging when everyone has other commitments, too.

“Developing games as part of a small team means you have everyone suggesting ideas and it’s easy to get carried away and continue to add features to the project which pushes your release date further and further out,” he explains.

“The key is to agree on a 'minimum viable product' spec up front and stick to it rigorously. New ideas can be added via updates later if need be.”

Mark Horneff, the managing director of Kuato Studios, which is behind big games like Dino Tales and Noddy Toyland Detective, agreed that the key is in the planning, whether you’re a one-man band or have a group of mates at your side.

“You need to carefully design and plan your app before you start to develop it,” he says. “There are plenty of resources out there to help, even if your budget is minimal.”

He cautioned that, while it's great to dream big, budding games developers shouldn't be over-ambitious. “Have realistic expectations as to what you can achieve in the time frame and within your budget – you might not necessarily invent the next 'big thing' but your sense of achievement will be worth it when you see your app on the App Store.”

Step 2: nail down your ideas

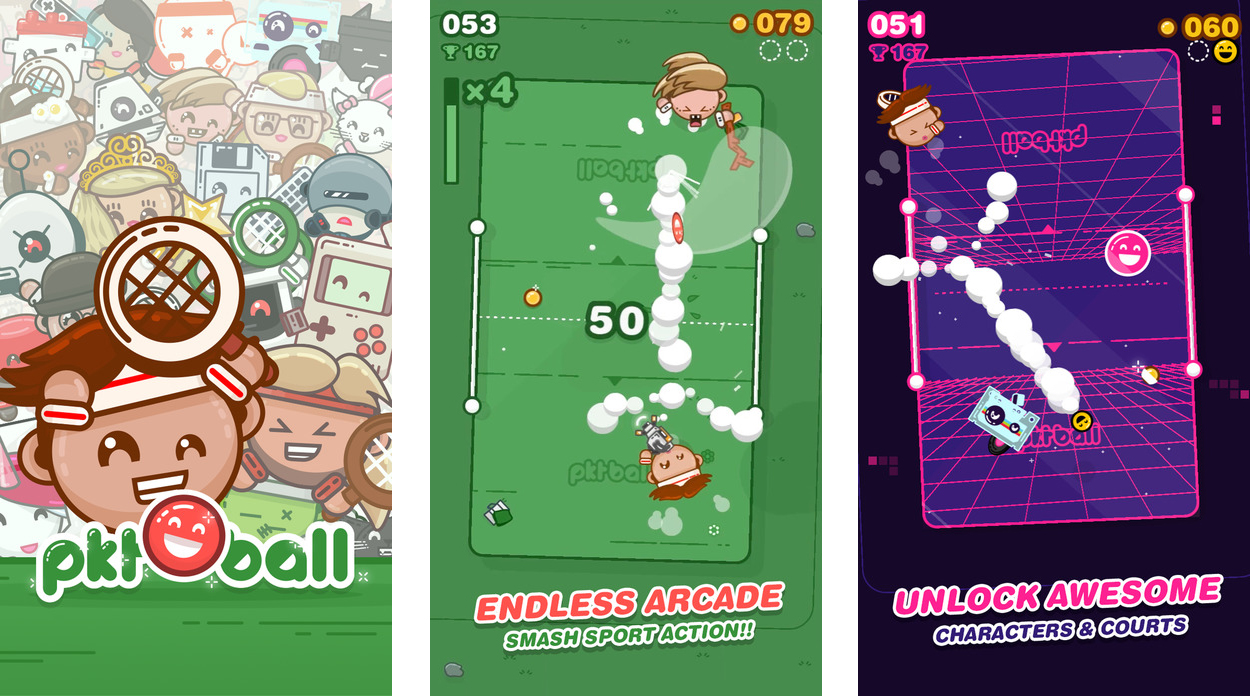

Rob Allison is a developer and co-founder of Laser Dog Games, a two-man independent studio behind games like Don’t Grind, ALONE and PKTBALL (which made Apple’s top 10 games for 2016 list). He tells us that one of the first things to think about when you’re dreaming up an iPhone game is to consider what sets it apart from the rest.

“There are so many developers out there working on mobile games, how is yours going to get seen?” He tells us. “This is always going through your mind while developing.”

Allison suggests stripping the process back to basics, and asking the question 'how will the game and controls work?' before thinking about more about design elements and the 'user journey'.

He adds: “Getting a control system that works well and is fun can be very challenging. We like to try unique ways of controlling the player rather than, for example, using on-screen buttons.”

Step 3: make sure you have the right skills

Allison works as part of a two-man team, and both of them get stuck into every process. “We’ve both had web design/development experience in the past, and luckily many of the same skills are used in game development,” he says. “We currently do all of the work – design, coding, artwork, music, marketing – in-house between the two of us.”

But, he says, a lack of experience shouldn't stop people from giving game design a go. “In terms of the actual coding, it’s never been easier. There are so many tools and tutorial out there. There are a lot of game frameworks to choose from also, most aiming to make the development time easier and quicker.”

He believes the key to success when you’re starting out for yourself is patience. “Making a game takes a really long time,” he adds. “It’s easy to underestimate how long it takes to refine an idea and turn it into a finalised project.”

Step 4: know what kit you need

When it comes to equipment, it can be really tempting to shell out for expensive new kit. But, other than a Mac and a lot of enthusiasm, you probably don’t need that much.

Chris Thomas tells us: “The main disciplines you lean on, depending on the type of game, are art, animation and code. Each has its own set of tools and software – for example most artists rely on Adobe's creative suite. In terms of equipment you really just need a computer, an iDevice and an idea.”

Becca is a contributor to TechRadar, a freelance journalist and author. She’s been writing about consumer tech and popular science for more than ten years, covering all kinds of topics, including why robots have eyes and whether we’ll experience the overview effect one day. She’s particularly interested in VR/AR, wearables, digital health, space tech and chatting to experts and academics about the future. She’s contributed to TechRadar, T3, Wired, New Scientist, The Guardian, Inverse and many more. Her first book, Screen Time, came out in January 2021 with Bonnier Books. She loves science-fiction, brutalist architecture, and spending too much time floating through space in virtual reality.