Airships are back. And this time they use graphene

Helium-filled Zeppelins will stay airborne 24/7

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Over three million people travel by air every day, but do the 10,000 aircraft in the skies as you read this represent a 'golden age' for aviation? Surely that belongs to the period between the two world wars when airships – the world's first passenger airlines – cruised around the skies conducting both luxury tours and scheduled services.

That was until New Jersey's Hindenburg disaster of 1937 crushed public confidence in airships, and they sank into history.

But airships are back. No longer a steampunk fantasy, there are advanced plans to fill the skies with helium-filled lighter-than-air machines for travel, cargo and even as emergency mobile phone masts.

Article continues below

What's changed?

So what's changed since 1937? Back then airships used highly flammable hydrogen, whereas now they rely on helium, which is completely inert and safe.

"It's also about modern materials and fabrics - the old 800ft airships had metal lattice works internal structure," says Hwfa Gwyn, Chief Financial Officer at Hybrid Air Vehicles (HAV), which has created the Airlander 10.

"Our vehicle is much shorter, much lighter with a pressure-stabilised hull of helium air, pressurised by a fan and valve system, but no other internal structure."

At 92m long, Airliner is still bigger than a Boeing 747 and can fly for as much as five days without landing. "We can fly three times further than a helicopter and carry many more people – 50 instead of 16 – in the Airlander 10, and do it for about a third of the cost," says Gwyn, who describes it as a "weightless plane" that gets 100% of its lift from that helium gas, which expands as it rises, and is completely safe.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

"You get a greater lift from hydrogen, but because of the risk we've never used it," he adds. To fill Airlander 10 with helium costs about £250,000, with only about 25% of it lost each year.

From next year Airlander 10 will be used for advertising, geo-surveys, offshore movement of people, delivering up to 50 tons of humanitarian aid or commercial cargo, coastguard search & rescue and, of course, by the military for 'eye in the sky' surveillance.

Vertical take-off

At its heart, the new drive for airships is about logistics – and a massive upgrade on the cargo-carrying abilities of helicopters.

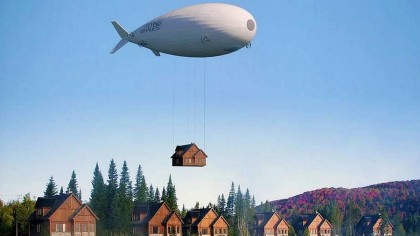

French company Flying Whales has developed a 140m-long airship, the 60-ton LCA60T, which will be manned by two pilots (though autonomous control is possible, too) while a third looks after loading and unloading cargo into its 75m-long suspended cargo hold.

It can take off vertically and travel at up to 100 kilometres/hour (or, at least, it will when Flying Whales launches a prototype in 2019).

"We're designing the LCA60T to be able to deliver a wind turbine to the side of a mountain, help transport electricity pylons or pre-fabricated buildings across undeveloped terrain and transport large aircraft components from one supply chain location to the next." says Sébastien Bougon, CEO of Flying Whales. The project is primarily for the French timber industry, though it's also funded by the China Aviation Industry General Aircraft (CAIGA) company.

Flying with graphene

The rigid-frame LCA60T also has a rather special electric propulsion system that uses graphene. Its hybrid electric power system uses graphene-based ultracapacitors – batteries – that give the airship a boost when it needs to hover, lift cargo, and stabilise itself in bad weather.

"Our ultracapacitor technology driving the airships' electric power systems will ensure manoeuvrability and control, such as vertical take-off and landing ability, which will be vital for heavy-lift industrial applications," says Taavi Madiberk, CEO and co-founder of Skeleton Technologies, which manufacturers the graphene-based ultracapacitors.

Industrial production of the LCA60T is expected to start in 2020.

Why do we need airships?

Aircraft need runways. While it's hard enough for busy airports to get permission for extra runways, it's even more difficult to construct them in remote areas. That poses problems for companies wanting to work in areas without roads, rail or navigable rivers; airships could make it possible to more easily mine for important metals and minerals, harvest trees, or build houses, wind farms, solar panel plants or construct electricity pylons in off-the-beaten track regions.

Airships could also be used to take humanitarian aid to earthquake or flood-hit areas, which are often the worst affected and least assisted.

"Aid very quickly gets into hub airports, but the difficulty is getting it to where it's really needed because roads and rail can get destroyed, so you're reliant on helicopters," says Gwyn. "Our vehicle can land on any reasonably flat surface and carry up to 10 tons."

Airships could also be used to bring communications to disaster-struck areas, or even to float extra mobile masts above Glastonbury Festival or sports stadiums. "It wouldn't rival something like Google's Project Loon – that's about low-cost internet – but for short-term, high value connectivity, Airlander10 could work very well," adds Gwyn.

Skunk in the sky

Although its Skunk Works plant in California has so far only produced a smaller prototype - shown at the Paris Air Show - Lockheed Martin claims that its LMH-1 Hybrid Airship will stretch to 91m and carry 23 tons of cargo - as well as 19 passengers - while also burning less than one tenth the fuel of a helicopter per ton.

Based on its earlier prototype the P-791, Lockheed Martin is hoping that the LMH-1 can one day be scaled-up as required for industrial applications to cope with as much as 500-tons of cargo.

Because it uses air cushions to land, the LMH-1 can land on rocky areas or even on water, so it's well suited to rough areas. The LMH-1 is being sold by Hybrid Enterprises using the hashtag #noroadsnoproblem. It's planned for 2018.

Winging it

For now, airship engineers are all at prototype stage, but the competition does look intense enough to herald a new age of airships.

As well as Flying Whales, Lockheed Martin and the Airliner 10, there are rival airships in development in Russia and Brazil. RosAeroSystems is promising the Aerostatic Transport Aircraft of the New Type (ATLANT) hybrid cargo-and-passenger airship, which takes off vertically and is being touted for VIP tourism and as an 'air yacht', though also as a way of transporting 60 tons of cargo up to 2000 km.

Meanwhile, Airship do Brasil already has a crewed airship that can take three tons. Future 140m-long iterations could carry 30 tons, probably for hydroelectric turbines, pylons and blades for wind turbines into the Amazon rainforest.

The future of airships

Though they promise to open-up the skies to truly global trade, airships are likely to be used first for something a little gentler.

"Airships have different flight properties and flight dynamics, but the uses for airships will be as varied as they are for fixed-wing aircraft," says Gwyn, who expects a £50 billion market across the next 20 years spread across commercial and military markets.

"But the first uses are likely to be in leisure and advertising." If you want to get ahead of the curve you can take a short flight in a Zeppelin now in Friedrichshafen, Germany.

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),