SpaceX: everything you need to know

The company that made space cool again

SpaceX has changed what we all think about space. Its reusable rockets that land back on the launch pad are a thing of wonder, but by now, relatively routine. Its massive Falcon Heavy rocket recently completed its first commercial mission without a hitch, and Space is now on the cusp of taking US astronauts up to the International Space Station (ISS).

Add some talk about missions to the moon, and ultimately the colonisation of Mars, and it’s no wonder that SpaceX is credited with single-handedly reviving humanity’s interest in space exploration.

What is SpaceX, who owns it and where is is based?

Founded in 2002, SpaceX is the creation of tech entrepreneur Elon Musk, now its CEO and chief designer. Musk, who founded what became PayPal, is also CEO of Tesla.

SpaceX has 6,000 employees and is headquartered in Hawthorne, California. It has a factory and a launch site in South Texas, and launch facilities at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (where it launches its reusable rockets) and Cape Canaveral Air Force Station (where it lands its reusable rockets) in Florida. It also has a launch site at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California.

What are SpaceX's long-term goals?

The colonization of Mars. How does one company help achieve that goal? By vastly reducing space transportation costs, that's how. Cue a 15 year+ project to create a reusable rocket launch system where the physical first stage of the rocket lands back on the launchpad once the payload has been jettisoned into orbit.

Musk believes that reusability is the key to making human life multi-planetary, which is necessary for our species because Earth could be struck by an asteroid, or become uninhabitable after a third world war. Musk thinks we need a backup plan, and his idea is to create a self-sustaining colony of a million people on Mars in the next 40 to 100 years.

However, the basic 'land a first stage rocket booster and use it again' part of the equation, though astounding in itself, was achieved way back in December 2015. Since then, SpaceX has been trying to make more components recoverable and reusable, and much more often. It's now developed a first stage that can be reused up to 10 times. Next up: the second stage.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

All this is for Mars. "It’s important to get a self-sustaining base on Mars because it’s far enough away from Earth that it’s more likely to survive [after a massive war] than a moon base,” said Musk at SXSW 2018.

"I’ve said I want to die on Mars, just not on impact," he once quipped, though whether he will achieve his wish remains to be seen.

Does SpaceX work with NASA?

Oh yes. In April 2019, NASA confirmed that it would pay $69 million (about £53 million, AU$97 million) to SpaceX to smash a Falcon 9 rocket into an asteroid as part of NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission in 2022.

Crazy science projects aside, the US national space agency and SpaceX have been working together closely for almost a decade. SpaceX has held NASA Commercial Resupply Services (CRS) contracts since 2008, and has earned over $1.6 billion (about £1.2 billion, AU$2.2 billion) by taking cargo up to the ISS from US soil in its Dragon capsules launched atop Falcon 9 rockets. These flights began in December 2010 and are ongoing.

However, that's not where the lion's share of its funds come from. SpaceX has earned over $12 billion (about £9 billion, AU$17 billion) taking large satellites and military payloads into orbit, and has conducted over 100 launches, including a record-breaking 19 launches in 2018.

The SpaceX Falcon 9 reusable rocket

Don't confuse Blue Origin's reusable rockets with those of SpaceX. While Blue Origin's New Shepherd rocket lands back on the launchpad, it's merely a sub-orbital rocket. The SpaceX Falcon 9 (and the Falcon Heavy, see below) is orbital-class, and regularly takes satellites and cargo into orbit. Soon it could take astronauts. Each Falcon 9 costs $62 million (about £48 million, AU$87 million).

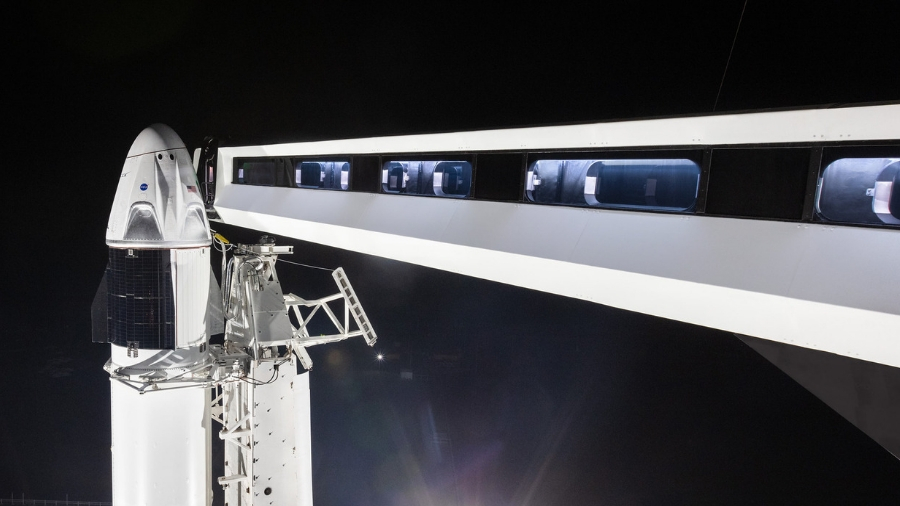

The SpaceX Crew Dragon reusable capsule

SpaceX won't accomplish want Musk wants until it can prove it's capable of carrying astronauts safely into orbit and back. That's what (along with Boeing) is contracted to do by NASA, which has been tasked with ending its reliance on Russia for taking astronauts to the International Space Station (which has been the case since 2011, when the last space shuttle was retired).

As part of NASA’s Commercial Crew Development program, SpaceX has developed an astronaut-friendly version of its Dragon 2 capsule – which has already visited the ISS as an unmanned cargo-carrier – called Crew Dragon.

Designed to carry six or seven astronauts, Crew Dragon is an ultramodern version of the old Apollo capsules. A successful Crew Dragon flight test called the SpX-DM-1 mission took place on 2 March, 2019, when Crew Dragon was launched on a Falcon 9 rocket. It successfully docked with the ISS, then returned to Earth. Next up, scheduled for July 2019, is SpX-DM-2, when two ex-Space Shuttle astronauts, Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley, will be inside Crew Dragon for a 14-day journey to the ISS and back. However, an unexplained explosion during Crew Dragon testing in April 2019 might delay things.

For now, Crew Dragon has to land on water and be recovered by ship, much like those Apollo capsules. In future expect to see a redesigned version of Crew Dragon that lands back on the launchpad.

The SpaceX Falcon Heavy reusable rocket

If you thought the reusable Falcon 9 rocket was impressive, try watching three of them land at once. That's what happens with Falcon Heavy, SpaceX's biggest launch system and the world’s most powerful operational rocket by a factor of two. The Arabsat-6A mission on April 11, 2019 saw the first commercial use of its Falcon Heavy rocket, which was tested for the first time on February 6, 2018 when it took Musk's Tesla Roadster and a dummy astronaut called 'Starman' into an Earth-Mars orbit.

With a maximum thrust of 2550 tons, the Falcon Heavy is essentially three Falcon 9 boosters. The two side-boosters come back to land simultaneously on the launchpad about 10 minutes after launch, while the central core lands on a barge in the Atlantic Ocean a a few minutes later. It's quite a show. Each Falcon Heavy costs $90 million (about £69 million, AU$126 million).

SpaceX and space tourism

Despite being the most high profile name in the space industry, and arguably also in space tourism (despite never having actually done any space tourism trips), SpaceX isn't actually focused on taking normal folk into space.

Yes, it does occasionally mention bizarre-sounding missions to the moon and Mars for private citizens, but only because the company is now laser-focused on developing a larger and cripplingly expensive rocket called Super Heavy. If anyone wants to pay huge sums of money to help test that rocket, SpaceX will happily take the money.

SpaceX and orbital space tourism

If you want to see the curvature of Earth for a few minutes, and experience weightlessness, before returning to Earth, look elsewhere. SpaceX has only orbital launch systems and any future space tourism offering from the company will involve Crew Dragon, long missions, and astronomical price tags. Orbital trips are very much the second phase of space tourism; Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic are only capable of taking people to the edge of space, not into orbit.

SpaceX is therefore likely to be about one-off and extremely expensive private orbital and/or lunar expeditions rather than space tourism. However, if the Bigelow Aerospace Private Space Station launches in 2021 then there will at least be somewhere for SpaceX to take space tourists to (NASA is not keen on having regular people stay on the ISS). Until then, there's only one other place for SpaceX to potentially take space tourists … around the moon and back again.

SpaceX and lunar tourism

Back in 2017 Japanese online fashion billionaire, Yusaku Maezawa wanted to reenact Apollo 8's dramatic first-ever mission to orbit the moon 50 years after that historic mission in December 1968. That would have meant using a Falcon Heavy rocket. However, the mission was cancelled early in 2018 so Maezawa could wait for SpaceX to develop a bigger rocket now called Super Heavy.

When that's ready, Maezawa and six artists (and probably a few astronauts) want to fly around the moon in 2023. That Dear Moon mission will last six days. However, it does require SpaceX to build a new rocket and spacecraft …

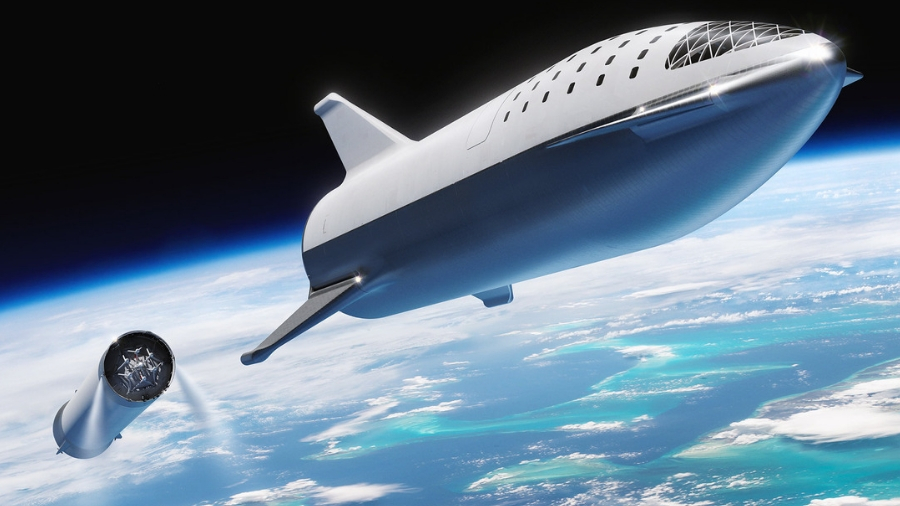

SpaceX's Starship and Super Heavy

Formerly known as the Big Falcon Spaceship (BFS), and Big Falcon Rocket (BFR), Starship and a 387-foot rocket called Super Heavy is a reusable launch system that SpaceX is now working on. Ultimately they’re designed to carry 100 tons of cargo and between 100 and 200 passengers to the moon and Mars.

From reusable rockets and a busy schedule of commercial satellite launches to taking NASA astronauts to space and, eventually, creating interplanetary transport, it’s fair to say that Elon Musk’s plans for SpaceX are ultra-ambitious. So far, we’ve got no reason to doubt his determination, and SpaceX is, for now, the most exciting company in a new and growing space industry.

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),