Is indie gaming the future?

When failure costs millions, do indies offer a solution?

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Being blessed with a strong independent games industry has always been one of the PC's strengths.

If you want to make a game, it's an open platform. There's no Sony, Nintendo or Microsoft to tell you that you can't do it, or anyone you need to suck up to for the tools. If you want to make a game then, dammit, you can.

Not only that, you can make just as big a splash as any of the biggest companies. The most attention-grabbing changes to strategy in the last few years for instance haven't come from a Command and Conquer or a Warcraft, but from the free Defense of the Ancients mod, and tower defence games.

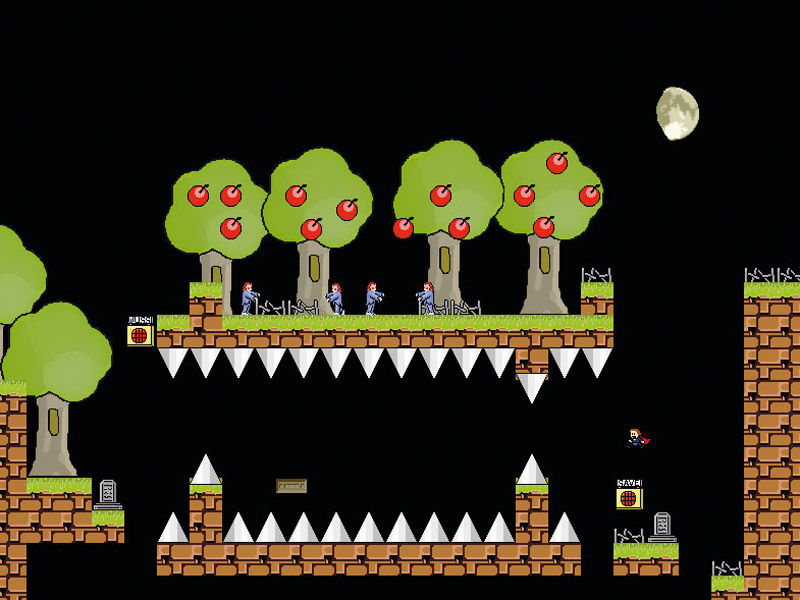

NEW AND IMPROVED: Demigod isn't just an updated version of Defense of the Ancients, but that's definitely the core of its action

The casual market has exploded, to the point that previously top-tier designers, such as Brian Reynolds and Levelord are no longer chasing after the huge AAA dollar, but the millions of smaller dollars from games, such as Farmville and hidden object games.

At the same time, devices such as the iPhone have opened up a huge new audience of people willing to drop 50p to £10 on a whim, and one where the little guy can do just as well.

ANGRY BIRDS: The iPhone can be filled up with games with the same lack of financial concern as dropping 50p into an arcade machine

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Take the example of Rovio. In 2003, it was three students with a game called King of the Cabbage World. By 2006, they were buying other mobile gaming companies. Now, its Crush the Castle-style game Angry Birds is on phones around the world, in all its sweetly frustrating glory.

Ages of independence

We're currently in a real golden age for independent games, with only one minor drawback – there are so many of them screaming for attention that many unfairly get overlooked or ignored.

Playing a Flash game on a portal such as Kongregate.com is quick, easy, and you're into the action almost as soon as you click on a link. Having to actually download a game almost feels like an inconvenience.

Actually playing a game, you're inundated with links to others, especially on the portal sites that use games to drive traffic to their adverts. When you find one you like, there'll be another along in seconds, tugging at your hand, wanting you to play in its own imaginative garden.

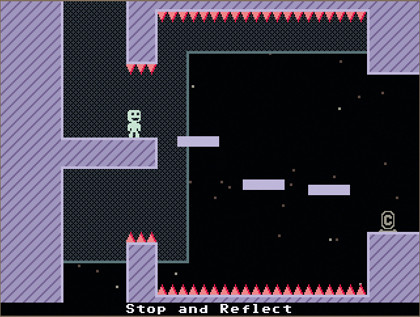

OLD SCHOOL: VVVVVV brings the frustration of games like Jet Set Willy to a whole new audience. And, in fact, the exact same audience too

For the most part, the ones that get attention are the ones that spread virally, typically via the blogs, and they usually go for a relatively small subset of what's available.

The constant flow of games mean that something with an instantly explicable gimmick will usually get far more attention than something complex and difficult to learn (a platform game versus an RPG, for instance) and free is always good, unless you're a developer eating ramen to survive.

Less immediately catchy games are frequently trapped in a niche of very specialised blogs and forums, which may not provide enough traffic to get enough people to pay up. Of course, getting cash has never been an easy thing.

The last golden age for the indie scene was the glory days of shareware, which began long before the internet made buying a new game a case of punching in a credit card number. The internet existed of course, but this was the early 1990s – it was still a dream for most UK gamers.

Instead, we had adverts for distribution companies in magazines, all proudly offering 'Try Before You Buy' software. For a couple of quid a piece, these companies sent catalogues and floppy disks stuffed with glorified game demos that could be anything from a few levels to a full game in their own right.

The idea was that you'd play this sampler, love it, mail off a cheque to the developers and – eventually – get the rest through the post. Needless to say, most people didn't actually bother with that last bit, at least not very often. It was easier and cheaper to get a stack of new games, and the generous size of shareware episodes compared to regular game demos made it a cheap way to fill your library. Still, many did.

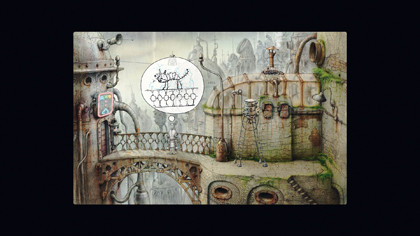

ARTISTIC FLAIR: The glorious art of Machinarium makes it a must-play, even if we did find some of the puzzles a little on the annoying side

Unreal creators Epic, which started as Epic Megagames, began this way in 1991 with the text-best dungeon crawl ZZT, before going on to publish other peoples' games, such as Tyrian and Jazz Jackrabbit.

Doom creator id software began life making platform games with names such as Rescue Rover and Dangerous Dave, before discovering a knack for 3D shooters with Hovertank and Catacomb 3D, and bringing the world Wolfenstein 3D and one of the most important shareware games of all time, Doom.

DOOM: It's tough to remember, but id wasn't only an indie developer once, but a shareware company that specialised in platform games

Independent games never went away, but they became temporarily less relevant after this. New technology such as 3D accelerator cards raised the bar in terms of what gamers expected, and made creating an industry-shaking game that much harder.

Instead of original games, attention primarily shifted to mods – levels, total conversions and other experiences built onto the top of existing games and engines, particularly from id and Epic.

In the last few years, the pendulum has swung back, mostly because of the popularity of tools like Adobe Flash, and the wide availability of game making tools, such as Adventure Game Studio, Blitz Basic and Game Maker. Why would you limit yourself to the audience of an Unreal game when you can use Unity 3D and actually sell your hard work?