Apple wants to make iPhones that ‘never fail’ rather than ‘super-easy to repair’ devices – but it’s not that simple

'A product that never fails is obviously better for the customer – better for the environment'

Apple's Head of Hardware Engineering, John Ternus, says his goal is to make iPhones as fail-proof as possible, rather than as repairable as possible. And while that sounds admirable, it's not quite so simple.

Speaking with content creator Marques Brownlee in an interview posted on X on May 29, Ternus told Brownlee: "I find it helpful to think about the book ends. So imagine on the one hand we've got a product that never fails. And on the other, a product that maybe isn't very reliable, but is super-easy to repair. A product that never fails is obviously better for the customer – better for the environment."

True, but there's a problem. And helpfully, Ternus explains this causal effect himself: "On iPhone, or any phone, a battery is something that if you want to extend the life of the product, it needs to be replaced, right? Batteries wear out."

Correct again, a battery that either doesn't wear out or can be very easily replaced would extend the life of the rest of your otherwise perfectly good handset. So what's the issue? It's one of the most cited reasons for iPhone failures to date: water ingress. The people want waterproof iPhones! Yes, and this has been achieved with the latest iP68-rated iPhone 15 series, which Ternus calls "really impressive" and the result of "making strides over all those years to get better and better and better, in terms of minimizing those failures". But according to the Apple executive, the downside is: "In order to get the product there, you need to design a lot of seals, adhesives, and other thing to make it perform that way, which makes it a little harder to do battery repair."

So, weatherproofed iPhones are ideal because they won't succumb to your smartphone's biggest killer – the demon drink (read: water). However, achieving that protection makes them harder to crack open and repair, most pertinently to install a new battery, which could shorten your handset's lifespan in other ways. You could call it the IP68 paradox…

$5 - Talked to John Ternus - Head of Hardware Engineering at Apple, and it was interesting hearing straight from the top why the iPhone is harder to repair. Take a listen pic.twitter.com/O9QsQOx4SPMay 29, 2024

There are various strands to unpick within Brownlee's interview. First off, Apple's 'product that doesn't fail' goal is admirable – but achieving that in one aspect seems to directly affect its viability in another. TechRadar's regular contributor and Apple expert, Alex Blake, told me: "Ternus has a point. Something that holds up better in long-term use and that doesn't need to be repaired will use fewer resources than something that is more repairable, but needs to be repaired in the first place. Reduce > reuse > recycle, after all. Getting a replacement part means another part needs to be made, so if you can avoid that by having something that doesn't need to be repaired, that's surely the better goal."

Exactly. So, consider the key part of your iPhone: its battery. We all know that lithium-ion batteries have a finite shelf life – according to the popular trade-in site, SellCell, it's the top reason people switch up their phone – and those cobalt, nickel and manganese-laden power packs are pretty toxic things to dispose of once they become unusable. Now, you almost certainly know that Apple will replace your flagging phone battery for a fee if you don't fancy buying a whole new iPhone, but there's another option, and it's one Apple might have left by the wayside.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You may have heard of the established technology that powers gadgets using only light sources, called Powerfoyle. This is non-toxic and made using responsibly sourced raw materials, and by harnessing it, Apple could ultimately do away with batteries – and thus negate those extra fees it charges to open your iPhone to spirit your old battery away. Powerfoyle is already on the market in audio products – the Urbanista Malibu headphones, the Urbanista Los Angeles and Urbanista Phoenix (the first ever light-powered earbuds) all use Powerfoyle for charging, as do the Adidas' RPT-02 SOL and Philips' A6219 GO.

Talking on sunshine?

So why aren't we all looking to that big shiny thing right above our heads for phone power? Well, brands have tried. Samsung was actually first to bring a solar-powered phone to market back in 2009, with the 'Solar Guru', or Guru E1107, but the handset was able to provide only 5-10 minutes of talk time after one hour of solar charging. In 2011, Apple patented a system to power to portable devices including laptops, tablets and phones using energy from the sun, but 13 years later, it's still not been implemented in any Apple consumer tech, let alone its most lucrative device – iPhone.

In 2016, various brands came clean about why our phones still aren't powered by the sun, admitting that harvesting enough light energy to keep your phone going was still a long way off. Why? One of the key stumbling blocks mentioned was the limited size of a phone's back cover upon which to place solar panels, thus restricting the extent to which the battery could be charged. Powerfoyle cells are basically solar cells without a glass cover that sort of resemble skin, rather than the stuff you see on top of houses, but they still need to be put on a physical surface that is exposed to the elements.

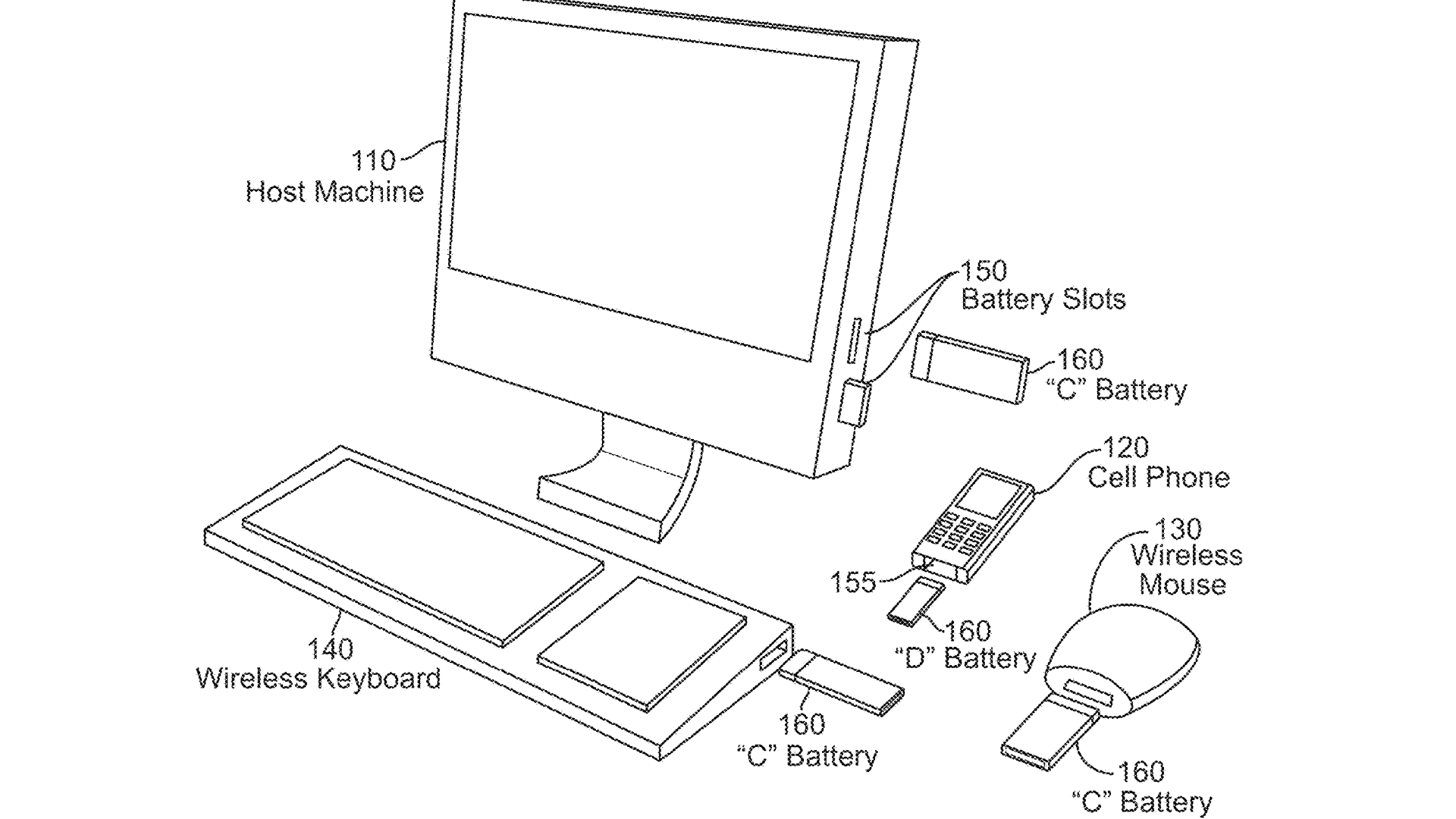

Cut to April 2024, and Apple recently filed a patent for removable batteries in those same devices it wanted to try to solar-power in 2011. It's hardly conclusive evidence that Tim Cook's given up on the sun – Apple files literally thousands of patents per year and many have yet to see the light of day – but while we can't say Apple is not working on solar-powered iPhones, we haven't heard much about it recently.

Anything ecologically special about the battery pack in the 2024 patent application from Apple? Not really – a cuboid core, an outer shell, positive and negative core terminals – images in the filing focused on the notion of standardized slots (think one battery to rule them all) rather than any special new tech in the power unit itself. And replaceable batteries will not solve any lofty environmental aims. It could be argued that any replaceable part introduces more points of failure, which in turn could lead to more replacement parts being needed, not fewer, ergo an iPhone that fails more, just for different reasons.

Bring it back (sing it back)

I'd argue that trying to deliver repairability is still preferable to an Apple guru telling a customer, "We've run diagnostics and there is one small, failed piece of circuitry in the iPhone, but it is not repairable. If it's under warranty we'll give you a new phone", as happened to me late last year, with an iPhone 11 Pro (in a strange issue that involved no water ingress). Ultimately, Apple faces a balancing act – how to make a phone last long enough that it doesn't need to be fixed, while also not making it a total write-off if something goes wrong. But to a degree at least, repairability is more environmentally friendly than the scenario above, because replacing just the small, failed component in my iPhone would have been better than canning the whole thing.

Apple devotees may call into question the financial viability of repairing tiny parts (it'll require highly skilled engineers, working actual, human hours), but other, smaller companies are going after this cradle-to-cradle approach. This type of manufacture means adhering to the ethos that every component put into a product should be able to come out again, and be reused, even in a totally different item – see the modular, easy-to-service Bang & Olufsen Beosound Theatre I got to hear in 2022 (below). And the ecologically-minded Danish AV specialist has recently been at it again, with a 2024 reissue of a vertical CD Player. In a triumphant nod to TechRadar's Sustainability Week 2024, the project involved finding units already out there, buying them back, taking them apart, servicing, re-anodizing (in a less wasteful way than we did in the '90s), and re-releasing them.

Back to the idea of replaceable batteries in smartphones for just a moment though, because it's hardly a groundbreaking notion. I loved the original Nokia 3310, released in 2000. Today, you could also pick up an inexpensive 2022-issue Nokia 5710 XpressAudio (which includes Bluetooth earbuds built in) or the August 2023 Nokia 130 and 150, all of which sport a delightfully switchable 1,450mAh battery.

No iPhone has ever come with a battery the user fits and updates themselves. In fact, the last time Apple offered a user-replaceable battery in any of its products was with the 2009 Apple MacBook.

Yes, an iPhone that never fails sounds like a very good idea. But if by 'never fail' the company means 'totally waterproof but hard to get into when your battery dies', it's a double-edged sword – and a line the Cupertino giant may struggle to justify further down the line. Nobody (least of all Apple) wants lithium-ion batteries corroding away slowly, stuck inside discarded IP68-rated handsets because it's too hard (or too expensive) to deal with. So, giving consumers what they want on both counts – a phone that doesn't succumb to water ingress but is also environmentally acceptable regarding its key components and their lifespan – is a difficult balance to strike.

You may also like

- See our pick of the best smartphones you can buy in 2024

- Know you need an iPhone? Our guide to the best iPhone 2024 is for you

- Use these 7 zero-effort smartphone apps to help you save the planet (and some money)

Becky became Audio Editor at TechRadar in 2024, but joined the team in 2022 as Senior Staff Writer, focusing on all things hi-fi. Before this, she spent three years at What Hi-Fi? testing and reviewing everything from wallet-friendly wireless earbuds to huge high-end sound systems. Prior to gaining her MA in Journalism in 2018, Becky freelanced as an arts critic alongside a 22-year career as a professional dancer and aerialist – any love of dance starts with a love of music. Becky has previously contributed to Stuff, FourFourTwo and The Stage. When not writing, she can still be found throwing shapes in a dance studio, these days with varying degrees of success.