The future of wearables

We look at how wearables are playing an increasingly vital role of our daily lives.

The future of wearables

There's always something exciting about a brand-new technology – it's raw and rarely perfected, but often loaded with seemingly limitless possibilities. Right now, that about sums up wearable technology – its part 'Apple Watch' but also part 'underwhelmed consumers'. In fact, you're as likely to read an enthusiastic review of the Apple Watch as you are reasons why you shouldn't care about wearables yet. To many, they're brilliant but baffling, powerful yet puzzling.

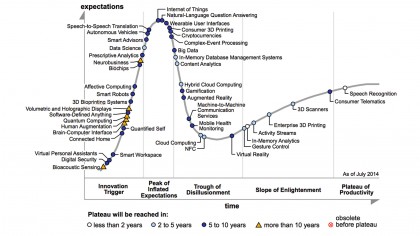

As with any new technology, wearables are surrounded by a busload of market hype. Even market research firm Gartner says as much. According to its latest yearly Hype Cycle of Emerging Technologies, wearable tech is right up there, having just fallen off the Peak of Inflated Expectation and begun the dive into the Trough of Disillusionment.

But that's not the end of the story – not by a long shot.

Massive money

At the same time, the potential for wearable technologies almost borders on the outrageous. For instance, Gartner expects some 25 million head-mounted displays will be sold by 2018. Rival analysts IDC forecasts a massive 173% jolt this year in wearable sales from 24.6 to 72.1 million. By 2019, it reckons that number will top 155 million, thanks in large part to a boom in sub-$100 fitness trackers. UK research firm, Juniper Research, sees the market for wearables tipping US$80 billion by 2020.

It's all part of what's being touted as the 'Intelligent Systems' market that includes everything from wearables to connected cars. IDC has a dollar amount it thinks this market will be worth by 2019 – a staggering US$1 trillion (US$1000 billion). No wonder you've got just about every company on the planet having a crack at something involving wireless connectivity.

Challenges

But peel away that hype and wearables still have plenty of work in front of them to get passed the novelty 'companion' tag. There are two key issues – one is perfecting the small-scale user interface; the other is electrical power. No-one is interested in a device that's more complicated to use than a VCR, nor do they want to carry a car battery in their pocket.

But possibly even scarier are the reports of consumers losing interest in their wearable devices – lots of consumers. Some of those reports are claiming as many as one-third of fitness tracker owners have downed tools after a few months; others fully one-half of users.

On the technology front, the reality is we haven't seen a new battery tech reach commercial maturity since the release of Lithium-polymer well over a decade ago. But there is real potential on the horizon – Stanford University's Aluminium-ion battery is one of the most promising developments this century and could turn the wearables industry on its ear. A battery that can charge in 60 seconds, recharge over 7500 times and is low-cost? Who wouldn't sign up to a boxful right now?

Seeing the future

While the Apple Watch has captured plenty of attention, the horizon is actually full of smart eyewear – and it's not all about consumers either. There's growing expectation that business could easily become the future driver of wearable technology.

For example, German logistics giant DHL carried out a pilot program in The Netherlands earlier this year in conjunction with Japanese technology maker Ricoh and German wearable tech company Ubimax. The program involved providing DHL warehouse staff with smart glasses rather than the usual hand-held product-picking devices. The result was a 25% increase in efficiency over the trial period.

And DHL's not alone – US smart glasses maker Vuzix has teamed up with enterprise software maker SAP to create two mobility apps – SAP AR Warehouse Picker and SAP AR Service Technician that work with Vuzix's M100 smart glasses.

The continued demand for efficiency savings all but assure smart glasses of becoming a corporate accessory for many industries. In fact, if you're a warehouse manager or in logistics, we'd be surprised if you weren't wearing a pair within the next five years.

Second-gen eyewear

The smart glasses landscape has clearly changed in the last couple of years since the initial launch of Google Glass. While lesser-known names like Vuzix and Ubimax are kicking goals in the corporate space, some of the biggest brands are also taking positions to grab a chunk of the market.

Chip maker Intel announced in June this year it had purchased Canadian-based Recon Instruments, maker of the sports-focused Recon Jet smart glasses. According to the announcement, the Recon team will now be part of Intel's New Devices Group, developing next-generation head-mounted displays.

And then there are the (so far) unconfirmed reports of Google Glass 2 nearing completion from Google. While the Mountain View company hasn't yet said anything officially, Ray-Ban and Oakley eyewear maker Luxottica let it be known its working with Google on version 2.0, which is also rumoured to have replaced the original Texas Instruments OMAP4430 dual-core CPU with an as-yet-unspecified Intel processor chip.

Headsets heating up

With Facebook flashing the corporate credit card to the tune of US$2 billion to grab hold of Oculus Rift, there's clearly no shortage of interest in the gaming headset market. And not surprisingly, old console rivals Sony and Microsoft are set to crank up the competition, although their plans go way beyond gaming itself.

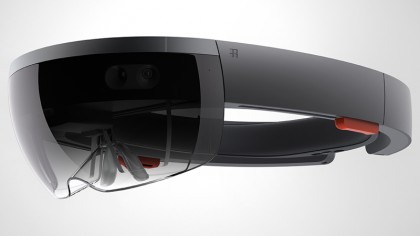

Microsoft turned heads earlier this year with the unveiling of HoloLens, its untethered holographic computer headset that augments your view of the world with 3D holograms. Like its Kinect sensor, HoloLens has applications extending well outside of the gaming arena and Microsoft is keenly promoting it as the ultimate accessory to almost any application, from Minecraft to its up-coming Windows 10 operating system, even introducing it into artistic and 3D modelling applications.

Meanwhile, Japanese giant Sony demonstrated its Project Morpheus VR, now named Playstation VR headset at the recent 2015 E3 gaming and entertainment expo, with the aim of bringing Oculus-style gameplay to the PS4 console. Sony is free enough with its basic specs – a full HD (1080p) resolution OLED panel, capable of up to 120Hz refresh rate and a latency (delay) time down to 18-milliseconds. This most recent second-generation hardware is also said to have faster and more accurate head-tracking than Sony's original incarnation. At this stage, however, Sony says we'll have to wait until 2016 before Morpheus hits store shelves.

But Sony has also been busy on the smart glasses front, releasing details on the SmartEyeglass and the clever SmartEyeglass Attach, the latter able to clip onto any pair of glasses. According to Sony specs, Attach features a 0.23-inch WVGA (640x400-pixel) display, but there's no firm release date or pricing details as yet. The developer version features a display panel is green-screen, 8-bit greyscale and 419x138-pixels, while Bluetooth 3.0, 802.11b/g Wi-Fi and a 3MP camera round out the major goodies on-board.

Payment wearables

The natural focus of much of the wearables market is on 'smart' devices at the moment, but they could also eventually change the way we gain entry and pay for goods and services.

One of the leaders in this market is US entertainment goliath, Disney, which has become an unlikely pioneer in wearable technology – and on a grand scale. It's using RFID (radio-frequency identification) wristbands to enable visitor entry into its resorts and theme parks, even for purchasing services (it gets linked to your credit card). The battery-powered 'MagicBand' can be purchased through the Disney Store and includes an array of customizations from bands to name-engraving. It has been said that Disney will spend US$1 billion on the whole system by its completion.

In fact, the corporate mindset in the US is turning in favour of bringing wearable technology into play. US customer management company Salesforce released a study earlier in the year on the intentions of businesses to implement wearable technology. It found that a third of the near-1500 respondents already implement wearables in the workplace and of those, 79% believe the tech either is or will be strategic to their company's future success.

Workplace wearables

Many of us use our own smartphones in the workplace. Chances are if you do and you're at a major company, you're part of a corporate 'bring your own device' (BYOD) program. But as the financial benefits of wearable tech continue to attract businesses like a moth to a flame, expect to see this expand into 'bring your own wearable' (BYOW) programs as well.

There's debate about when it's likely to begin, but we think it's inevitable – and here's why.

Healthcare is fast becoming one of the major battlegrounds for wearable tech in the US, where employer-funded health insurance is often a key part of an employment contract.

Unlike in Australia where the vast majority of employees cough up for their own insurance, healthcare cover in the US isn't cheap – but companies are finding ways to reduce their premiums, including issuing fitness trackers to employees. Jiff is one of the players in this new enterprise health benefits market and according to Fortune magazine, is already available to some 300,000 US employees including from companies such as beverage maker Red Bull and games developer Activision Blizzard.

What price privacy?

It's part of a growing trend in corporate US where businesses are encouraging employees to join 'wellness' programs, which can be as specific as taking part in challenges such as agreeing to drink so much water, eat certain foods or walk so many steps a year for various incentives.

But while on the surface improved employee health outcomes and lower corporate healthcare premiums sound like a win-win, there are growing concerns about the cost to employee and consumer privacy.

In the US, a PricewaterhouseCoopers study found that 86% of respondents were concerned wearable technology would make them vulnerable to security breaches, while 82% also feared an invasion of privacy (page 41). The reports' authors make the point that 'the more we outfit ourselves with data-gathering devices, the more exposed we are'.

The real gold isn't hardware

For while there's an obvious market in smart glasses, watches and fitness bands, there's possibly an even larger market to consider.

In a similar way to how network access charges are potentially more valuable than the smartphone itself and how replacement inks can often cost as much as the printer, the gold isn't necessarily the wearable hardware, but in the mountains of data these devices will inevitably generate – data about your health, your activities, your buying patterns.

In signing up for social media and other online services, we all tend to fly by the end-user agreements and privacy policies in a hurry to join, but the data we leak is valuable. In fact, if we're asking what price our privacy, it turns out, quite a bit.

The UK's Financial Times in 2013 sighted what it said was 'industry pricing data' on various bits of consumer information and found that the names, age, gender and location of 1000 people was worth 50cents - in other words, next to nothing. But throw in more personal information about specific health conditions and that information sold for 26 cents per person. It still sounds like nothing, but start looking at it by population and the numbers really begin to add up. Back in 2012, business advisory firm Boston Consulting Group found the value hidden in the personal data of EU consumers - their 'digital identity' - could 'deliver a €330 billion annual economic benefit for organisations in Europe by 2020'.

Is your personal data secure?

And because wearables are still very much a nascent technology, we should be asking questions about data security as much as privacy.

Researchers from security firm Symantec put together some home-made wireless scanning devices in 2014 using off-the-shelf components built around Raspberry Pi computers. Taking these devices out on the road to public spaces in the US, the researchers not only picked up a range of fitness trackers being used, they were able to track the individuals wearing them.

Even worse, they also found rookie data security mistakes such as unencrypted passwords transmitted in plain text.

The bumpy road ahead

There's no doubt that wearable technology can offer many benefits – from improved health and lifestyle outcomes for consumers to efficiencies and cost-savings for business. But as the wearables market now begins hitting its straps, don't under-estimate the value of data security or how much your personal data is worth.

Before you sign up to your next wearable device offering online data collection, make sure you check the brand's data-use policy and find out as much as you can about its data security. You might be signing up for more than you bargained for.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful