Read or dead: is this the end for the ereader?

Could ereaders be reaching their final chapter?

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

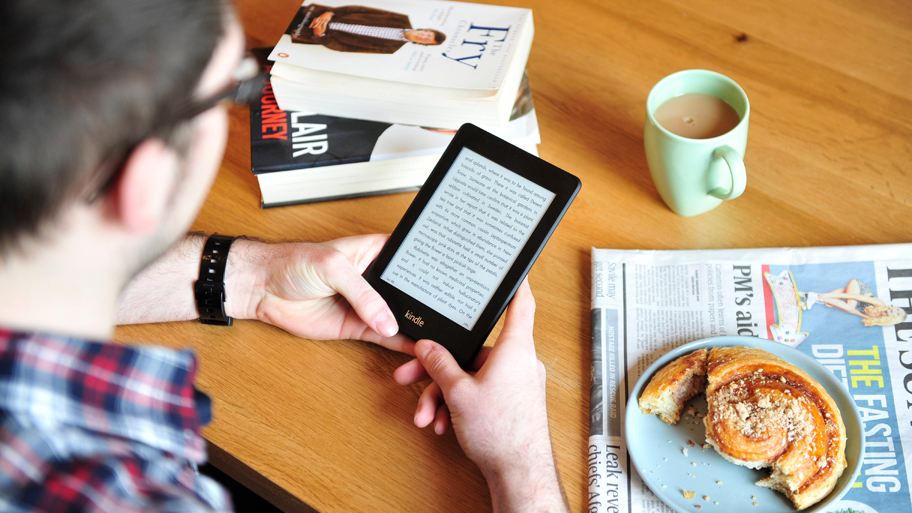

Do you read books on your phone? If you do (perhaps while leaving your e-ink Kindle in a drawer to gather dust) you'll know that the way we're consuming books is changing fast.

The invention of the ebook caused a seismic shift in book publishing, but the ereader it gave rise to could be on the wane. With the release of Amazon's Kindle Fire HD tablets and most recently its big screen Fire Phone, has Amazon killed the ereader it created?

The e-ink Kindle, the Kobo and the Nook could now all wane as we see a new genre of tablet-based books that contain much more than mere words.

Ereaders through the ages

"The dedicated ereader may well have a limited lifespan," says Darren Laws, CEO of UK publisher Caffeine Nights. "Amazon recognised this and has been building toward a natural transition. People used to talk endlessly about e-ink and eye strain, but these topics are no longer on the agenda. Now it's all about multi-functionality."

It's also about age. Research in the UK by the St Ives Group found that 36% of adults own an ereader (half of them received it as a gift), but only 4% of people surveyed read solely on a digital device.

Tellingly, however, this figure rises to 66% among those aged between 18-34. While 18% say they can read a digital book just as well on a tablet, that figure rises to 32% of those aged 18 to 24. The ereader has a demographic bomb under it.

The e-ink ereader is old technology, but we're not talking about the device itself. "Amazon is smart. It knew it had to develop a stable platform first and did this through the more traditional reader who saw the transition of book to ebook as a progression," says Laws. "Amazon tapped into a more conservative market and the grey pound, converting many older readers to new technology."

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Laws thinks that older readers continue to adopt ereaders, while younger readers increasingly use tablets. "Amazon's next challenge, and that of the publishing industry, will be how to transition older readers to newer technology than ereaders," he says. "This may take some time or be a natural progression as the market matures, so dedicated ereaders may be around for a while yet."

The boom in ebooks

While ereaders will do well to have a long-term future, the ebook itself is doing just fine. The increasing use of multiple devices to read the same book, via the Kindle app for smartphones and tablets for instance, is not necessarily a bad thing for publishers. The St Ives Group found that those who read both physical and ebooks get through about 50% more than those who only use one format rather than both – about 27 books a year on average versus 18.

Instead, readers with the most devices read the most books. "Anything that encourages people to read in their leisure time is good for the industry," says Laws. "It doesn't matter if they are picking up a traditional hardback or paperback or scrolling through a list of downloaded titles on their tablet or ereader. What publishing is offering is the choice of how they would like to consume their books, and that can't be a bad thing."

The enhanced ebook

One effect of the shift towards reading on bigger smartphones (the Amazon Fire Phone has a 4.7-inch screen, with Apple's upcoming iPhone 6 rumoured to come in 4.7-inch and 5.5-inch screens) and tablets could herald the birth of enhanced ebooks.

Thus far, the print-to-digital migration has largely been text and few images, but as the ebook format comes to dominate, creative publishers are trying to use the medium of digital to blow wide open the boundaries around what is considered a novel. "Enhanced reader-interactivity with a digital text is soon likely to become commercialised on a mass scale," says Dr Gregory Leadbetter, Director of the Institute of Creative and Critical Writing at Birmingham City University.

"Hyperlinks will act as online footnotes, taking readers to images or videos of places mentioned in the text, or atmospheric soundscapes, or critical commentary, all at the touch of a button."

The rise of interactive ebooks may not be inevitable, however. "Enhanced ebooks have not really taken off yet despite many fantastic multi-layered ebooks being available that contain a mix of audio and visual media," says Laws.

"People still want to read plain text and get lost in their imagination and not have their imagination mapped out for them – for that we already have films."

The power of the paperback

If the future of plain text is assured, so to is the humble paperback. "I see a new appreciation of the book as a physical object," says Leadbetter. "I know several users of e-reading devices who have gone back to books. As a technology, the print book has the advantage of functioning without a power supply, unless you count a reading light, maybe, and it is easier on human eyes. Importantly, a book also has tactile qualities that tablets and ereaders cannot reproduce."

Even if the choice of books offered through a tablet or ereader far outweighs that which can be carried around as paperbacks, some readers will also be drawn to paper, with a whopping 51% preferring to buy paper books, according to the St Ives Group's research.

"I don't foresee the extinction of print books with the rise of digital reading, especially if print publishers are sensible and don't try to fight the convenience of digital technologies," says Leadbetter. "For example, they should make e-versions available to purchasers of print versions, to develop habits of dual enjoyment."

That already happens with movies; Blu-ray and DVDs often now come with a licensed digital copy in the cloud called UltraViolet, which can be downloaded to multiple platforms and devices. So why not with books?

Reading the future

More choice can only be a good thing and that includes both paper and e-ink devices. While tablets are entering classrooms, Leadbetter also believes that the textbook will continue to be paper-based for many years to come. "Children will most likely continue to learn to read and write through print and paper, rather than screen-based technologies, again, for the sake of their eyes, if nothing else, and that freedom from electronica will remain a possibility for them, as it remains for all of us."

Nor does everyone think that the migration from ereaders to tablets for reading will cause the death of the e-ink tech. "I think ereaders will maintain their popularity," says Matt Graham, Technical Consultant at app developer Apadmi in London, which developed the BBC iPlayer Radio app as well as apps for The Guardian. "Amazon has by no means killed the ereader, because its tablets and phones do not replicate any of the USPs of an ereader, namely very long battery life, the ability to read in bright light, and no eye strain when reading for prolonged periods."

Barnes & Noble's plan to separate from the Nook arm of its business suggests that the ereader may no longer have economics on its side, but it's likely to stick around as a cheap Christmas gift for the foreseeable future.

Whether or not the ereader's status as a "genuine replacement for a book with no drawbacks", as Graham puts it, is enough to save it from long-term extinction is a different story.

- All might not be lost for e-ink, especially if devices like the YotaPhone become popular, with an LCD screen on the front and an e-ink screen on the back.

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),