Hashtags that save lives - the end of slacktivism

Tweet the change you want to see in the world

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

By now the success of the Ice Bucket challenge is fairly well known. The money raised by the viral challenge has led to a medical breakthrough that could ultimately help to find a cure for the debilitating motor neurone disease ALS.

At the time, the Ice Bucket Challenge was tarred with the same brush as many online movements – scathingly dubbed ‘slacktivism’. The idea is that sitting on your phone, liking a tweet that supports a cause is a futile endeavour; that social media isn’t capable of really making a difference.

But is this really the case? Mark Zuckerberg clearly doesn't feel so. He has recently changed Facebook's mission statement in an attempt to make Facebook a force for good. He believes that together we as a global community can defeat poverty, terrorism and even climate change.

Obviously the Ice Bucket Challenge has proved to be far more than an exercise in altruistic narcissism, but is it the exception or the rule?

Opening up lines of communication

We were invited to an event hosted by Facebook to talk about how social media can be used to promote causes. At the event we got to meet the driving forces behind two social media movements of the moment: Luke Ambler, the hugely inspiring person behind #itsokaytotalk, and the seriously cool team behind #CookForSyria, Serena Guen and anonymous food blogger Clerkenwell Boy.

Ambler started the #itsokaytotalk hashtag as a continuation of the work he was doing at a group called Andy’s man club. The group is named after his brother-in-law Andrew, who tragically took his own life last year. Andrew became one of the 12 men a day that take their own life, and Ambler felt something had to be done, so he started a group where men could meet and talk about their issues.

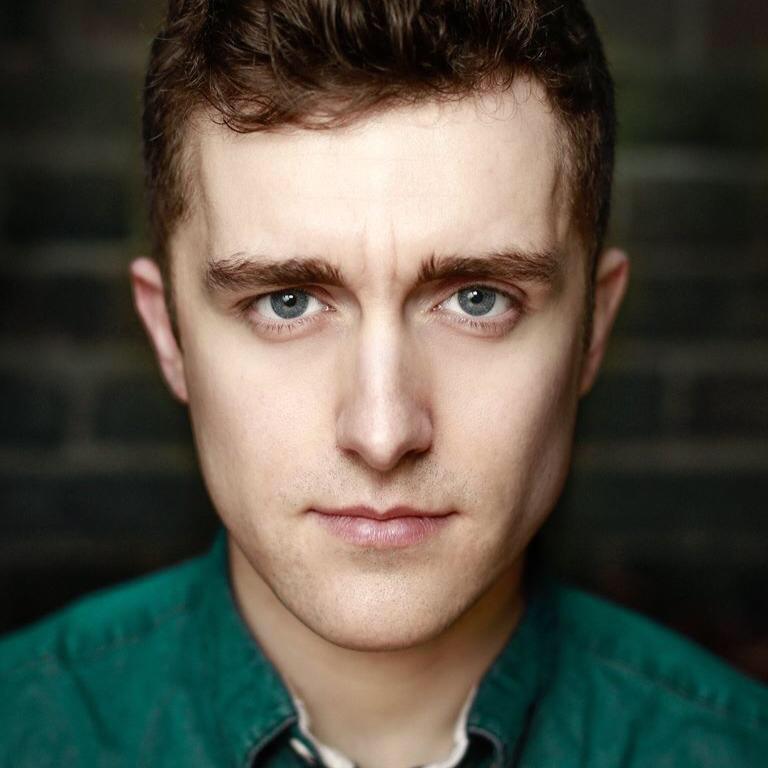

What’s really striking about Ambler is that he’s so far removed from what you would imagine a man figure-heading a movement about emotional expression would be like. He’s a tower of a man, clearly a rugby player (he used to play professional Rugby League), with a deep northern accent. But when he talks he’s open, honest, and incredibly kind.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Luke Ambler: "This Isn't a Gimmick; We're Here for the Long Haul." https://t.co/aSkoFCmzyr pic.twitter.com/eWQ3NCsMWcJanuary 21, 2017

“Andy’s man club was a group set up last year when my brother-in-law took his life,” Ambler says. “Two weeks after, we set up the group. First week nine men turned up to talk about how they’re feeling and express their emotions, then 15 men, then that’s how we started the it’s okay to talk campaign … grabbing your phone, taking a selfie, letting the world know that it’s okay to talk. Within four weeks 100 million people had done it, and it’s growing every day.”

So clearly the movement has struck a chord. When we asked Ambler why he felt it was particularly men that needed this movement he said: “Because 80% of suicides in [the UK] are by men. It’s the single biggest killer for us under 45. We’re more likely to die by suicide than anything else.”

They are sobering statistics, but Ambler has a theory as to why so many men are choosing to take their own lives: “I guess the inability to speak out, and that comes from being conditioned from kids to be a man, not be a girl. Don’t cry. Don’t show weakness.”

The reason that social media is so important in this movement ties directly into this. Social media allows for a strange social dynamic where you can both be involved in a group but also have anonymity, meaning that those who previously wouldn’t have felt able to be involved in a conversation now can be. Showing weakness and sharing your problems become much easier if you can see others doing it too.

Came close twice in the last year. Talking saved my life both times. #itsokaytotalk #WorldSuicidePreventionDaySeptember 10, 2016

This is something Ambler is particularly passionate about: “Often when people have got a problem that they’re struggling with they don’t want to go to someone else, because they believe that people are dealing with their own stuff and they don’t want to burden other people with their problems.”

“But we’ve found that to be B.S. to be honest, because Andrew,could have been a hundred grand debt, nothing he could have done would have matched the burden of what he’s left now.”

It's too early to say how many men have been or could be helped by Ambler's #itsokaytotalk campaign, but the signs are encouraging if this tweet is anything to go by:

Cooking up a storm

Founded in 2016 to raise money for people affected by the crisis in Syria, the #CookForSyria movement has raised over £150,000 (about $190,000, AU$250,000), with the movement reaching over 170 million people worldwide.

The movement started when publisher, businessman and philanthropist Serena Guen contacted food blogger Clerkenwell Boy to talk about how they could help. Guen told us: “Clerkenwell Boy and I were talking about what we can do for Syria. I asked him if he wouldn’t mind hosting a small dinner and he was like: ‘No! Why would we do that? Why would we do something so small when we can do something a lot more impactful?’

“So basically we came up with this idea of doing a big launch event. We had six really famous chefs; everyone from Angela Hartnett to Yotam Ottolenghi, José Pizarro. And we launched a month of Syrian food in London. We had over a hundred restaurants signed up, we had about 50 official partner restaurants, and they each took their signature dish and put a Syrian twist on it, and then funds would go to Unicef.”

“Then people were hosting supper clubs and things in their homes, using the recipes from the website. That all culminated in the cookbook for Christmas, which actually became the number one middle eastern cookbook on Amazon. And then it kind of turned into a global movement after that, it really got picked up.”

Cooking for change

Cooking and charity are an obvious partnership, but the online community provided by technology means that this movement can have far greater reach than your standard bake sale. Clerkenwell Boy said: “It’s the supper club that became a global movement. And the idea is that anyone, if you’re a professional chef, or a home cook, or just interested in food, you can get involved by cooking for Syria.”

Guen also thinks food can help people relate to an issue that’s at risk of becoming unfathomable. “I think it all just becomes so dehumanized,” she says “People are having problems relating to the numbers. Six million children in Syria are currently affected by the crisis. No one can even fathom what that means, but someone can understand what hummus is.

“It’s in their daily lives. And hummus came from that region. And it gives them a tie to that region. It makes them care about something, and also they can learn about the region.”

What’s interesting is the way Guen talks about the role that social media played in the movement: “There’s no way that the campaign would have taken off so quickly if we had to use traditional media outlets. The time it would have taken to create a buzz would have been months, but something needed to be done now.”

And this immediacy is something the internet does best. If a campaign goes viral then you’ve instantly reached millions of people. But this strength is also its weakness, as we learnt with the Kony2012 campaign. You can see the very powerful video below.

Created by a group called Invisible Children, the YouTube video was the first major example of viral charity fundraising. Watched more than 100 million times in six days, it captured the hearts and imaginations of many people all over the world. The problem was, Invisible Children had some dodgy practices, and a leader who disgraced himself. Kony was never caught.

So the question is, given the great power that the internet bestows on charities and organizations, or even individuals who wantto do good, should there be some form of moderation of these movements? Or is the risk of getting duped just part of being altruistic, whether online or in real life?

Whatever the answer, we think it’s fair to say that slacktivism deserves more respect than its moniker suggests.

Andrew London is a writer at Velocity Partners. Prior to Velocity Partners, he was a staff writer at Future plc.