Dog-sized scorpions, dinosaur shrimp, and exoplanet collisions lead the week in science

Prehistoric fauna and pursuing absolute zero made our week

From megafauna and massive anthropods to an exoplanet that got hit so hard it had the wind literally knocked out of it, science news has definitely been lively this week.

On the biology front, a newly discovered fossil of a meter-long scorpion was the first of its kind in Asia, while scientists now believe they have conclusively proven what killed off the woolly mammoth. Arizona park attendees were also treated to the rare emergence of "dinosaur shrimp" whose ancestry stretches back to before the reign of the dinosaurs.

On the physical sciences front, researchers have come closer than ever before to absolute zero, the coldest temperature physically possible for matter to reach, using an exotic state of matter and a really tall tower.

Out in the furthest stretches of outer space, astronomers caught a white dwarf star turning itself off and on again while another team discovered evidence of an exoplanetary collision that can only be described as a doozy.

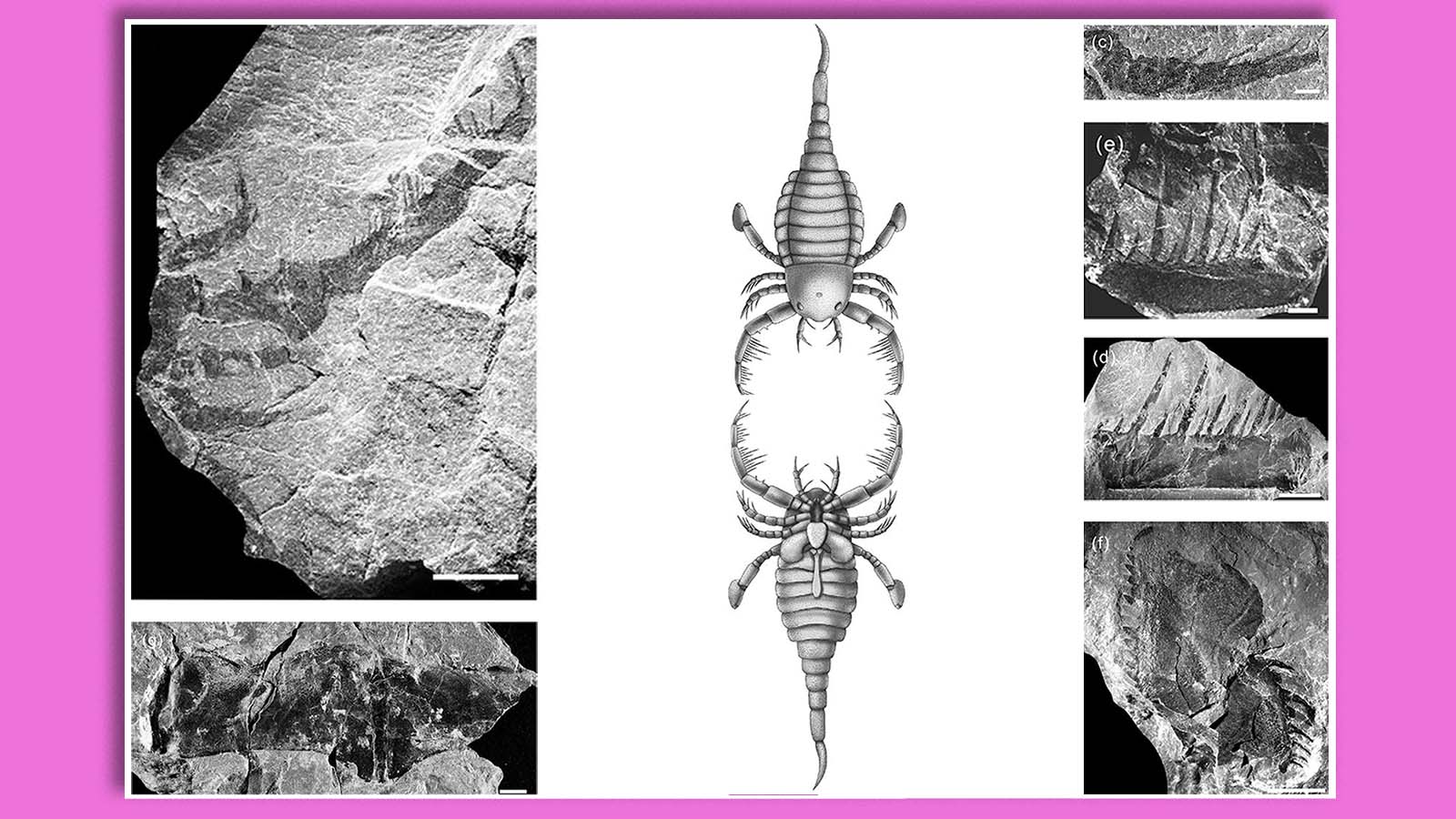

Ancient Dog-Sized Scorpion Fossil Found In China

A large, prehistoric fossil of a sea scorpion was found in the Lower Silurian region of South China, the first time a large eurypterid has been identified in Asia.

The fossil, which belonged to Terropterus xiushanensis gen. et sp. nov., was a member of the Mixopterids, a branch of eurypterids (sea scorpions) characterized by specialized arms that were lined with spikey teeth that were used to gather up prey in a terrifying, basket-like embrace.

"Our knowledge of these bizarre animals is limited to only four species in two genera described 80 years ago: Mixopterus kiaeri from Norway, Mixopterus multispinosus from New York, Mixopterus simonsoni from Estonia and Lanarkopterus dolichoschelus from Scotland," the researchers wrote in the study.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

This new discovery expands on our knowledge of these prehistoric sea predators, which lived between 443.8 million and 419.2 million years ago.

Scientist Achieve Coldest-Ever Recorded Temperature

In a record-shattering experiment, scientists in Germany achieved the coldest temperature ever recorded, just 38 trillionths of a degree Kelvin above absolute zero, the physical limit of how "cold" matter can be.

Temperature is a measure of molecular motion. The more movement, the more molecules collide with each other, which generates energy that we experience as heat. So, the coldest possible temperature is achieved when there is no molecular motion at all, which occurs at -459.67 °F / -273.15 °C, or 0 on the Kelvin scale.

In order to achieve a temperature of 38 picokelvins, the scientists had to force about 100,000 rubidium atoms into an exotic state of matter called a Bose-Einstein condensate and then simulate deep-space conditions using Bremen University's 120-foot tall drop tower. You can read more about this record-shattering experiment here.

Three-eyed 'dinosaur Shrimp' surprise park attendees

Last July, monsoon rains in Arizona led to the hatching of hundreds of three-eyed "dinosaur shrimp", delighting attendees at Arizona's Wupatki National Monument.

The longtail tadpole shrimp, officially Triops longicaudatus, were spotted swimming in a pool created by the rains that filled up a preserved ball court at the historic site. "We knew that there was water in the ball court, but we weren't expecting anything living in it," Lauren Carter, lead interpretation ranger at the monument, told our colleagues over at LiveScience. "Then a visitor came up and said, 'Hey, you have tadpoles down in your ballcourt.'"

While sometimes referred to as a "living fossil", the description isn't quite accurate. The morphology of the triops has remained largely unchanged for 70 million years, that doesn't mean they are the same shrimp that coexisted with the dinosaurs.

"I don't like the term 'living fossil' because it causes a misunderstanding with the public that they haven't changed at all," Carter said. "But they have changed, they have evolved. It's just that the outward appearance of them is very similar to what they were millions of years ago."

Astronomers watch white dwarf 'switch on and off'

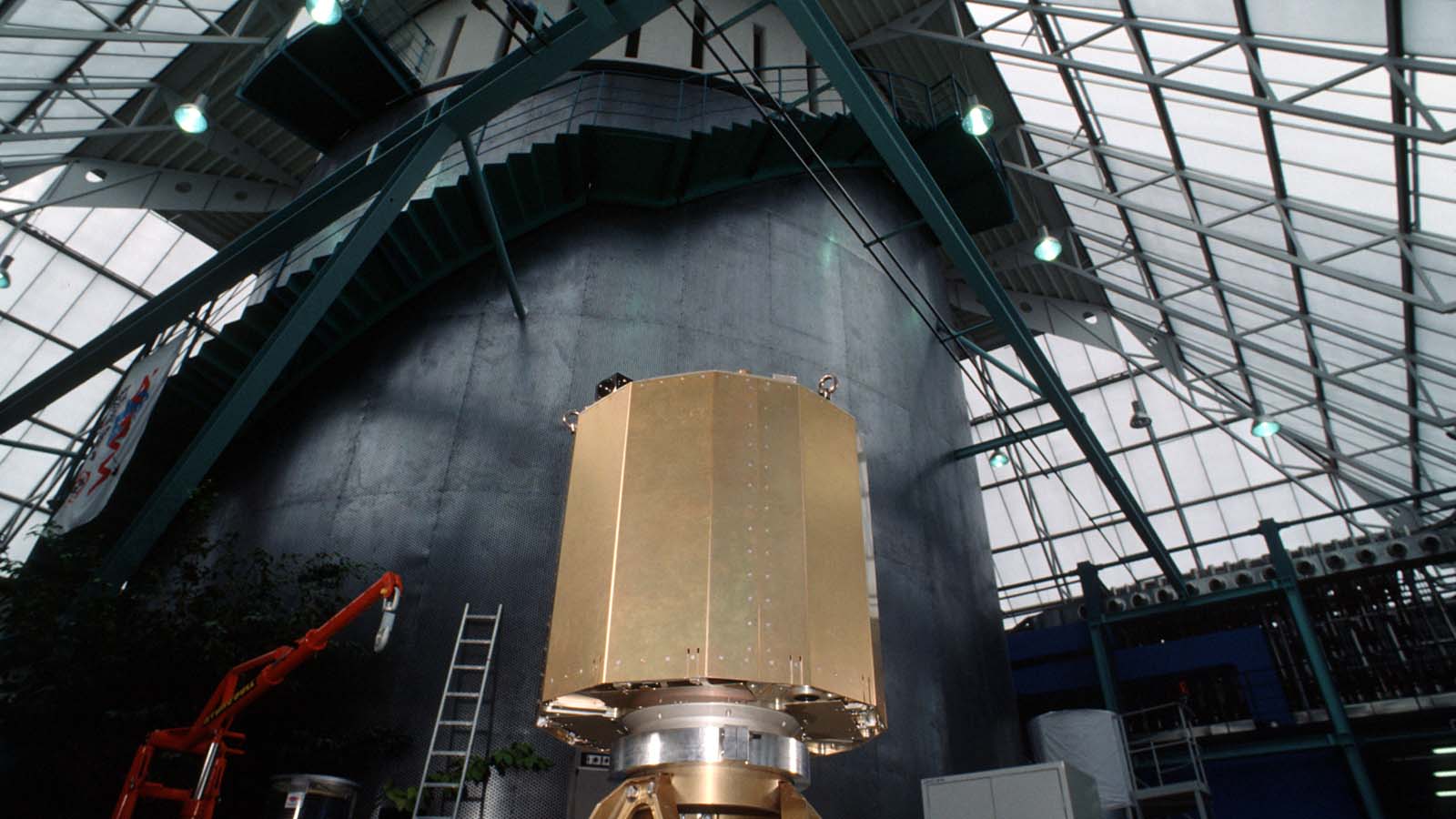

Astronomers at Durham University, UK, were looking at data from NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) when they spotted something remarkable: a white dwarf star that appeared to be turning itself "on and off" over the course of as little as 30 minutes.

Dr. Simone Scaringi, who led the new research, was investigating the mechanics of material accretion around the white dwarf to get a better understanding of how accretion works with more exotic, and thus rarer, objects like black holes and neutron stars when she spotted the "switching" behavior.

The white dwarf is part of a binary system known as TW Pictoris, and the white dwarf is sucking up material from its partner star, making it a valuable subject for watching accretion at work.

"In general the accretion process does not have any short-term 'gaps'," Dr. Scaringi told TechRadar. "What generally happens in these types of systems is that the donor star in orbit around the white dwarf keeps feeding the accretion disk. As the accretion disk material slowly sinks closer towards the white dwarf it generally becomes brighter, and eventually makes it onto the white dwarf surface."

Scaringi believes that something about the white dwarf's magnetic field is acting as a kind of magnetic gate mechanism that hasn't been observed before.

"Once the amount of material has nearly drained out entirely, this is when so-called 'magnetic-gating' acts: the spinning magnetospheric barrier of the white dwarf prevents left-over disk material from simply accreting smoothly, but instead regulates the amount that lands onto the white dwarf in 'fits and starts'.

"As it takes months to drain a disk out, seeing TW Pictoris drop in brightness in 30 minutes was totally unexpected," Scaringi told us. "What we think may be happening in TW Pictoris is that instead of the disk being drained out so fast, we are seeing some sort of reconfiguration of the white dwarf magnetic field, which promptly pushes the inner-disk edge outwards, and thus makes it fainter."

Climate change drove woolly mammoth extinct

Woolly mammoths have been a subject of endless fascination for humans ever since their discovery in 1796, but there has been a heated debate in the past hundred years particularly about what drove these cousins of the modern elephant to extinction. Now, an exhaustive study of nearly 20 years worth of biological samples says that the woolly mammoth succumbed to climate change, not human activity.

"Scientists have argued for 100 years about why mammoths went extinct," said Professor Eske Willerslev, director of The Lundbeck Foundation GeoGenetics Centre, University of Copenhagen, and a Fellow of St John’s College, University of Cambridge.

"Humans have been blamed because the animals had survived for millions of years without climate change killing them off before, but when they lived alongside humans they didn’t last long and we were accused of hunting them to death.

“We have finally been able to prove was that it was not just the climate changing that was the problem, but the speed of it that was the final nail in the coffin – they were not able to adapt quickly enough when the landscape dramatically transformed and their food became scarce."

As the glaciers melted after the last ice age, the change in climate was so drastic that the snowy steppes and the hard-scrabble plant life that sustained the massive herds of the megafauna disappeared. What replaced it was a wetter tundra with radically different plant life that was ill-suited for the massive mammoth herds.

Even though humans are technically exonerated in the death of the woolly mammoth, that doesn't mean there aren't important lessons to draw from the mammoths demise.

“It is a stark lesson from history and shows how unpredictable climate change is," professor Willerslev said, "once something is lost, there is no going back. Precipitation was the cause of the extinction of woolly mammoths through the changes to plants. The change happened so quickly that they could not adapt and evolve to survive.

“It shows nothing is guaranteed when it comes to the impact of dramatic changes in the weather. The early humans would have seen the world change beyond all recognition – that could easily happen again and we cannot take for granted that we will even be around to witness it. The only thing we can predict with any certainty is that the change will be massive.”

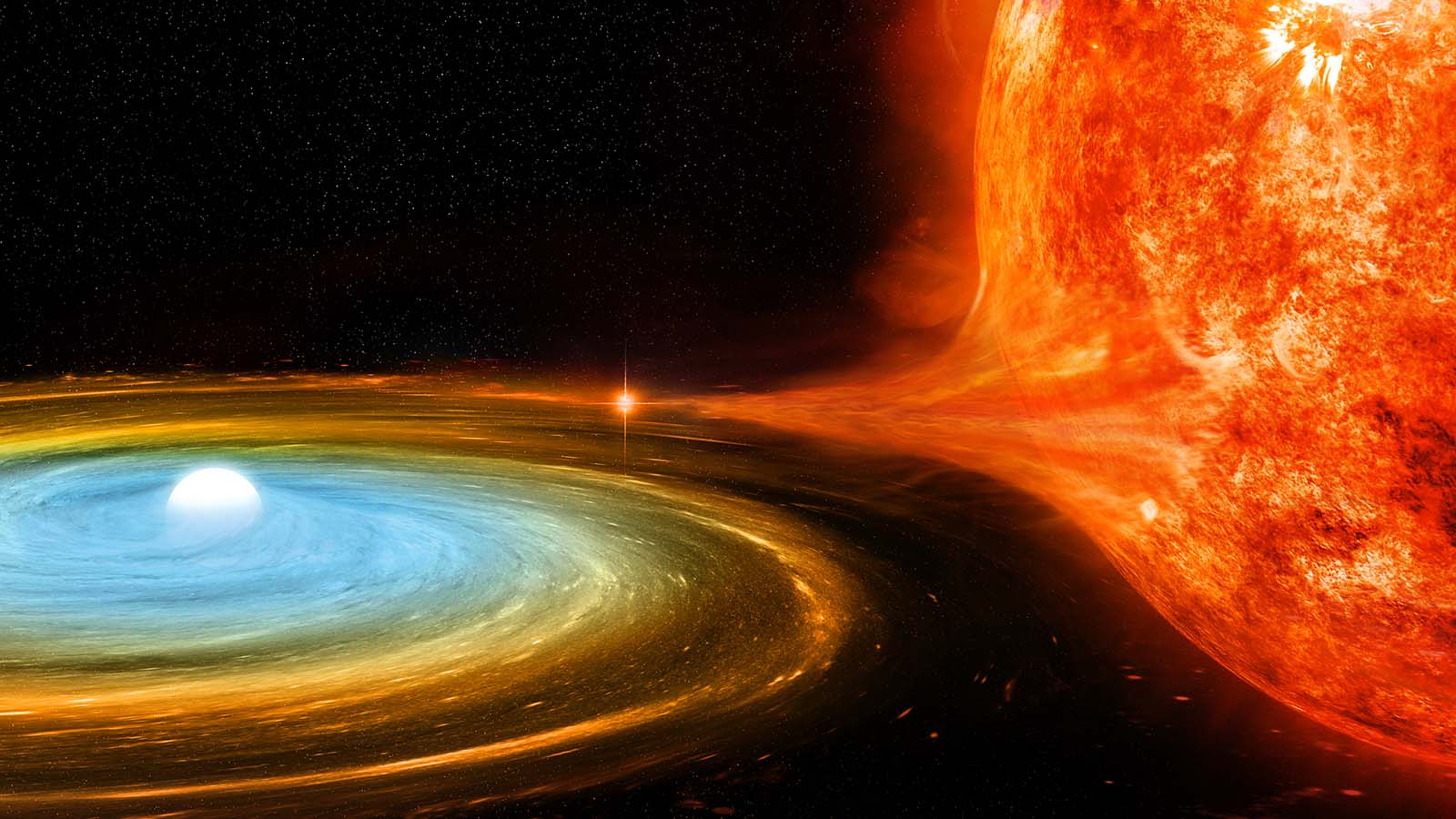

Exoplanet has atmosphere stripped by collision

This week, astronomers announced that they've found evidence of an exoplanet collision so powerful that it stripped the impacted planet of a huge part of its atmosphere.

The planet in question is in the star system HF 172555, which hosts a relatively young star, which is only about 23 million years old. The system is particularly interesting since there is still active planetary formation taking place, and an examination of the amount of gas among the protoplanetary debris reveals strong evidence of a violent collision in the recent past.

By studying the amount of carbon monoxide (CO) present in the debris disk around the star, which is typically broken down by stellar radiation pretty quickly, the astronomers found that about 200,000 years ago, a collision between an earth-sized planet and a smaller impactor occurred that stripped the larger planet of a huge chunk of its CO atmosphere.

For comparison, the amount of CO gas in the disk indicates that a volume equivalent to about 20% of Venus' atmosphere was stripped off by the collision and thrown into orbit around the star.

“This is the first time we’ve detected this phenomenon, of a stripped protoplanetary atmosphere in a giant impact,” says Tajana Schneiderman, a graduate student in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences and lead author of the new study, which was published this week in the journal Nature. “Everyone is interested in observing a giant impact because we expect them to be common, but we don’t have evidence in a lot of systems for it. Now we have additional insight into these dynamics.”

John (He/Him) is the Components Editor here at TechRadar and he is also a programmer, gamer, activist, and Brooklyn College alum currently living in Brooklyn, NY.

Named by the CTA as a CES 2020 Media Trailblazer for his science and technology reporting, John specializes in all areas of computer science, including industry news, hardware reviews, PC gaming, as well as general science writing and the social impact of the tech industry.

You can find him online on Bluesky @johnloeffler.bsky.social