Obituary: JG Ballard, the original cyberpunk

England's greatest sci-fi writer charted "the psychology of the future"

The English science-fiction author and novelist JG (James Graham) Ballard has died this week, aged 78, after a long battle with prostate cancer.

Ballard was equally revered and vilified throughout his writing career due to his uncompromising style and often bizarre (but consistently fascinating) ways of thinking about the multiple effects of technology on humanity.

Slashdot contributor 'meehawl' sums up Ballard's influence on writers and technologists, as being "the epitome of supremely ironic indifferent technophilia and, as such, a template for our hyper-connected present."

The first cyberpunk

The writer famously said that his books were "picturing the psychology of the future" and he became a huge inspiration on younger cyberpunk writers such as William Gibson and influential postmodern philosophers such as Jean Baudrillard.

Ballard was also a massive influence on popular music, with his dense, surreal and frightening riffs on technology and modernity inspiring hundreds of bands and songwriters.

Aside from his more mainstream novels, such as Empire of the Sun – Ballard's memoir of childhood experiences in a Chinese prisoner of war camp (later given the Hollywood treatment by Steven Spielberg) – he will be remembered and celebrated by sci fi fans for his dystopian and unforgiving accounts of the impact of modern technology upon the landscape and the human psyche.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

We live in Ballardian times

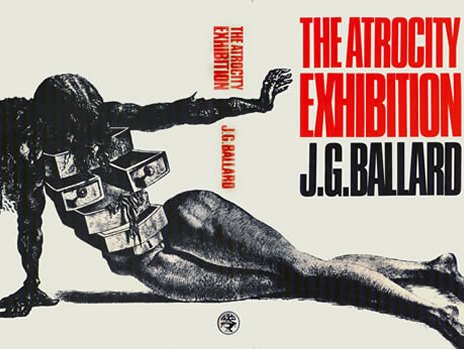

The adjective 'Ballardian' entered the English language after the publication of his more extreme novels and short stories from the late 1960s and early 1970s such as The Atrocity Exhibition and Crash (later made into a controversial movie by David Cronenberg).

The Oxford English Dictionary defines 'Ballardian' as: "resembling or suggestive of the conditions described in JG Ballard's novels and stories, especially dystopian modernity, bleak man-made landscapes and the psychological effects of technological, social or environmental developments."

Ballard's friend and fellow author, Iain Sinclair told the BBC: "He was one of the first to take up the whole idea of ecological catastrophe. He was fascinated by celebrity early on, the cult of the star and suicides of cars, motorways, edgelands of cities.

"All of these things he was one of the first to create almost a philosophy of. And I think as time has gone on, he's become a major, major figure."

The future is boring

"I would sum up my fear about the future in one word: boring," Ballard famously said, in his typically contentious way.

"And that's my one fear: that everything has happened; nothing exciting or new or interesting is ever going to happen again... the future is just going to be a vast, conforming suburb of the soul."

Though it should be stressed that Ballard was in no way a Luddite recommending a return to some pre-technological, pastoral utopia.

"Science and technology multiply around us," he regularly noted, making liberal use of the languages of technology and science in his work. "To an increasing extent they dictate the languages in which we speak and think. Either we use those languages, or we remain mute."

Technology is nasty and commercial

Ballard will continue to be revered among readers and writers alike for his unforgiving stance on the many confusing and messy impacts of everyday technologies.

"Electronic aids, particularly domestic computers, will help the inner migration, the opting out of reality," he said, long before the internet mediated our daily reality.

"Reality is no longer going to be the stuff out there, but the stuff inside your head. It's going to be commercial and nasty at the same time."

Ballard's final book was his magisterial autobiography Miracles of Life – a fascinating account of a life, though marked with immense tragedy, lived to the full and an insight into the writer's growing obsessions with technology and its impact on the people he saw around him and the cities he lived in.