How Dune's production team brought the world of Arrakis to life

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There's a saying among Hollywood's most revered directors that filmmaking shouldn't be about serving the audience, but the filmmakers themselves. Denis Villeneuve's Dune just so happens to do both.

The French Canadian auteur's adaptation of Frank Herbert's seminal science fiction novel is a rare passion project that reminds viewers of the value of cinema in the age of streaming. Huge in scale and high in decibels, Dune takes audiences on a thoroughly convincing trip across the stars to the sweltering deserts of Arrakis, never once losing the identity of its source material – nor the vision of its new creative steward.

But behind every great director lies an equally accomplished production team, and on Dune, Villeneuve assembled the Avengers of modern filmmaking.

Ahead of the movie's release on digital download (January 17), 4K UHD and Blu-Ray (January 31), TechRadar sat down with not one, but three members of this star-studded supporting cast: Visual Effects Supervisor Paul Lambert, Head of Production Design Patrice Vermette and Director of Photography Greig Fraser.

What follows is the inside story of how Dune was made, as told by the team behind the camera.

Built from the sand up

It's difficult to know where to begin when offered the chance to interview three filmmakers who, though working on the same movie, each performed very different roles. Lambert, Dune's multi-Oscar-winning Visual Effects Supervisor, starts by emphasizing the teamwork involved in bringing such an ambitious project to life.

"Dune was a fantastic collaboration," he says. "Denis is a visionary, but he does take input from all of his heads of department and, having worked with him before on Blade Runner 2049, I knew that [Dune would be] all about photorealism. It wasn't about any fancy virtual cameras – everything had to be grounded in reality. And because of that, we were given time to work out different techniques, to make sure we could be as photoreal as possible.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

"We spent six months in pre-production, and every day we would meet and discuss various different ideas. It was very much a practical push to get as much as we could on camera, and, obviously, there was CG work as well, but that was always surrounded by something real – like an actual ornithopter."

As Lambert explains, Villeneuve's desire to maintain the illusion of reality throughout Dune's 155-minute runtime (which the director himself detailed in a separate interview with TechRadar) extended from the largest set-pieces right the way down to the smallest props.

"Denis never wants a visual to take you out of the experience," he says, "so that's why things like the blue eyes aren't overly done. It's a very small part of the movie. There's a subtlety, a want for the audience to believe what they're actually seeing. And that goes for [the Baron's] sludge, the huge bases and all the explosions, too. We also tried to avoid things which were overly digital. We just tried to make everything as believable as possible.

"I had also been working with Patrice [Vermette] for eight months before I joined pre-production," Lambert adds, "which meant I had figured out a lot of the visuals already. We built the sets in Budapest, and I built those virtual worlds based on those concepts."

"Denis never wants a visual to take you out of the experience"

As for how those concepts went from the mind of Dune's chief production designer to 70-foot IMAX screens all over the world, the story is a little more romantic.

"Actually, Denis came to me and said, 'I want you to dream,'" Vermette tells us. "So I went back to the book before reading the script, and I started piecing together all the different cultures and planets. And you start, very, very wide. So I gathered references for everything that was emotionally evoked through the book – ziggurat architecture, imperial Japanese architecture, deserts in Iran, Yemen, even Mars.

"Then all of a sudden, some of those images start to blend together," he says. "Some make sense, others don't, but you build a mood board of visual references and start sketching. And that's how we built the world."

Despite being a science fiction story awash with political fantasy, though, the world of Frank Herbert's novel remains – in keeping with Villeneuve's aforementioned commitment to realism – strangely plausible. As such, Vermette sought to build a conceptual picture of Arrakis with real-world practicality in mind.

"You also start with logic," he says of his approach to Dune's production design. "You put yourself in the position of the person who first founded Arrakis and think, 'okay, with winds going at 800 kilometers an hour, I would put everything at an angle so the wind sweeps over the buildings.'

"Then with the interiors, you don't want to have direct sunlight because of the heat of the planet. So you build thicker walls that would keep the cool air inside, just like in a cave. And then you introduce some cultural elements like the murals on the doors, or the way that the doors themselves are made, then you start digging into furniture.

(At this point, we suggest to Vermette that he'd make a great interior designer should he decide to leave filmmaking behind. He chuckles, agreeing unashamedly.)

"It’s about adding all of these elements together – they're not necessarily things that are written on the page, rather things that support the words that are there."

Like a kid in a candy store, Villeneuve's cinematographer on Dune, Greig Fraser – whose next project is none other The Batman – offers an answer to the question of first steps that betrays a filmmaker enamoured by the unusual freedom afforded by the movie's sizeable budget.

"What I love about Denis is that he comes from this French Canadian cottage film industry, which is not dissimilar to the Australian or English film industries, [with broadcasters] like the BBC," Fraser tells us. "So we all come from this world of character-based drama, and when you suddenly get given a little bit of extra funding, you start to dream bigger.

"You ask yourself, 'can we drop Jason Momoa from a construction crane in the desert?' Absolutely. We wouldn't have been able to do that on a small film. But you can dream bigger when you have the chance."

For readers who haven't yet seen Dune, there is indeed a scene in which Jason Momoa plunges from a great height into the sand. But we ask Fraser if an increased sense of pressure came hand-in-hand with that freedom to push boundaries.

"If you think about the daunting nature of what you're doing when you're doing it, you wouldn't do it," he says. "So we'd take one day at a time, one scene at a time, one problem at a time, and all of those sequences added up to a bigger picture."

Old friends, new flick

For Fraser, Dune marked the first collaboration with Villeneuve. Both Lambert and Vermette, though, had worked alongside the director before (on Blade Runner 2049 and Arrival, respectively). As such, they were already familiar with his passionate, almost obsessive filmmaking style – a familiarity that gave them the confidence to lead with their own ideas.

"Denis and I have a long history together," Vermette explains. "We've known each other since the 90s. We come from the same type of family background. We like the same type of music. We like the same type of art. We've had many discussions on multiple subjects before getting into this movie. So we have a shorthand.

"But strangely enough," he continues, "we don't talk that much. I'd show him what we created in the art department, but we know each other well enough for him to [be focused on] other things. It's like we're mentally connected."

Lambert, in contrast, was acutely aware of what Villeneuve wanted from the movie's visual effects – but he, too, reveals a moment when he brought his own creativity to the table.

"This is a project which Denis had been thinking about since he was a teenager," he says, "so he had very, very, very specific visions in mind for the movie. Our job was to try and implement those visions to the best of our abilities.

"But for the hologram sequence, we came up with a cool idea. I wanted to avoid doing a full-on CG close-up of Timothée when he enters the hologram bush – [it would have been difficult] to get all that interactive light on his face. So we presented an idea to Denis – bearing in mind that he had already signed off on what the holographic bush would look like – where we took that bush and sliced it into hundreds of slices.

"Then," Lambert continues, "we projected those slices onto Timothée with an actual projector. We also tracked his body position, so every time he moved, a different slice would be projected onto him, and that gave us the perfect interactive light. Then all we had to do in CG was put the holographic bush around him. It was a technique I've not done before, but it was actually really, really successful."

Ripples in the sand

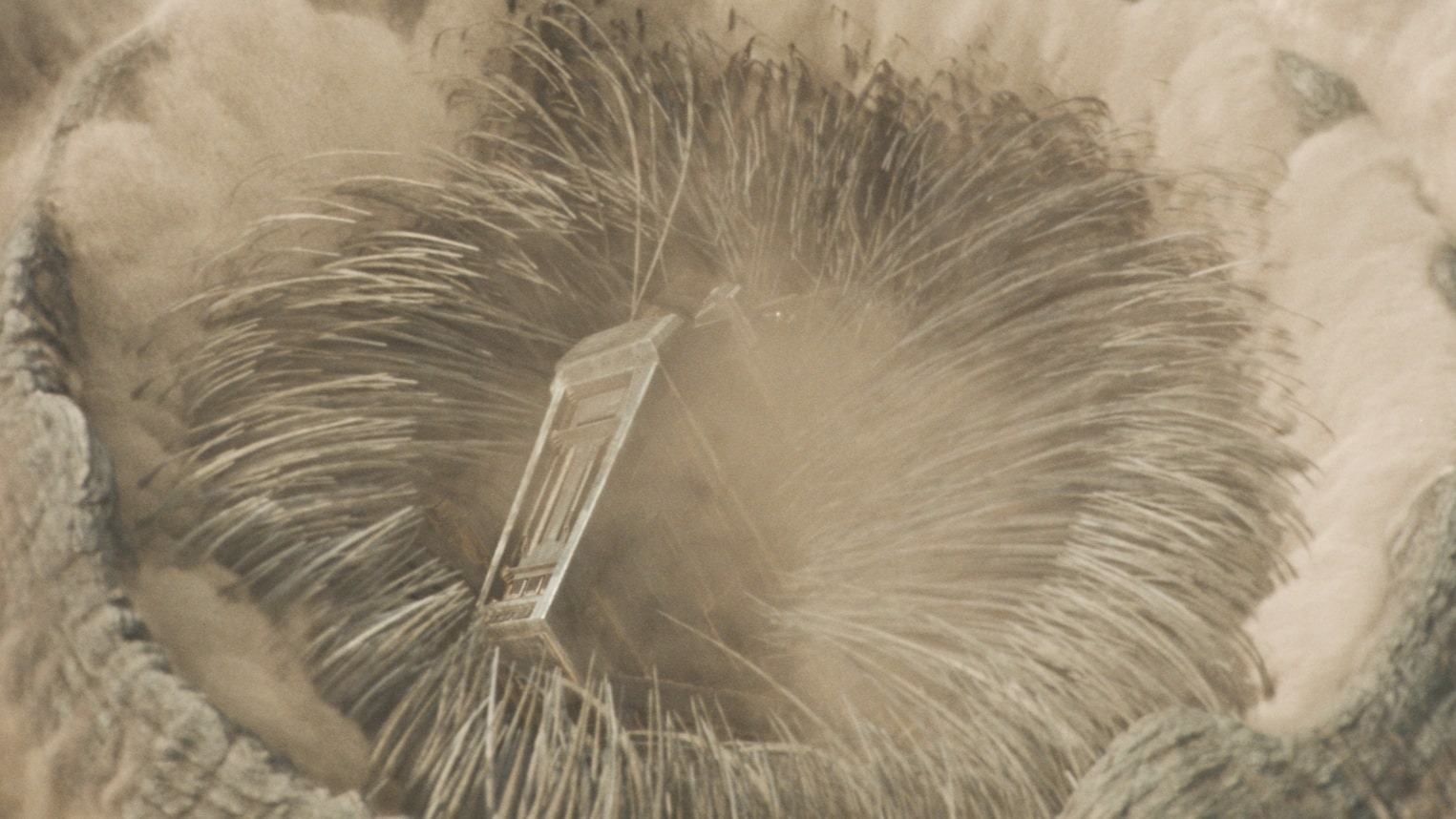

Holographic bushes weren’t the only visual effect Lambert had to grapple with, though. Inarguably the most iconic part of Frank Herbert's fictional planet, the colossal, dune-shifting sandworms presented a very particular challenge to all involved on Dune.

"I knew that one of the biggest problems – well, not problems, hurdles – was not the worm itself, but the sand surrounding it," Lambert explains. "Any successful visual effects are always based on something real, and you can't really find any [situation] where you have that much displacement of sand. I knew it would be problematic in visual effects to try and make that believable."

"It's also so computationally expensive to simulate [that level of displacement], so there was plenty of trial and error. In fact, there was a good year of development before we actually started to drop [those sand effects] into shots."

But Vermette, again playing the naturalist overseeing the world of his creation, explains his desire to see Herbert's sandworms treated with the respect afforded them by the novel's native people, the Fremen.

"It was important for us to show that the worm was not so much a terrifying creature, but more like a mythological, godlike creature," he says. "And that's why, when it opens its mouth, it looks like the sun.

"So when we started working on the idea of the worm, I was thinking, 'what would that worm actually eat?' You know, it doesn't start crunching. And very early on, the great [blue] whale was in the discussion. We thought [the two creatures] might eat in the same way, with filtration as opposed to chewing."

As much as Vermette maintained an interest in the misunderstood grace of Herbert's sandworms, though, he was equally concerned with accurately portraying their scale on screen.

"Obviously when the worm moves, there's no way it could be underground and not transform the landscape around it. So when we fly over Arrakis [in the movie], pay attention to the details – it's super subtle, but you can see traces of their movement, like footprints."

A display of authenticity

You don't have to be a film expert to watch Dune and realize the magnitude of the technology involved in its production. As Lambert alluded to, many sequences in the movie – the holographic bush, the emergence of the sandworm – relied upon the existence of state-of-the-art visual effects software.

But Villeneuve and his team didn’t turn to the latest technology in every instance.

"We had discussed using LED screens [on Dune] because Greig [Fraser] had done the first season of The Mandalorian using that technology," Lambert explains. "But we knew we couldn't get that harsh intensity of light with an LED screen.

"Also, Denis has got this saying: nature supersedes the storyboard. He adapts the scene when he turns up on set. It’s a very organic process. So trying to set up everything prior to shooting doesn't really work with him, because he likes to think on his feet. It's terrifying – but also exhilarating."

We later press Fraser for a more detailed explanation as to why he and Villeneuve opted to shoot Dune without any of the LED displays the former had used so effectively on The Mandalorian (for clarity, these are modular panels that allow actors to exist in virtual movie worlds without the need for traditional green screens).

"Well, here's the thing," Fraser says. "We were still filming The Mandalorian as we were prepping Dune. So The Mandalorian was a practice exercise [for that technology]. We were still trying to work out the bugs in the system. That prep was happening concurrently with Dune.

"Also, you can't just say, 'hey, let's do some [LED] screens.' You've got to pick a path [in advance], but the path wasn’t forged yet because The Mandalorian was in the process of forging it. So it wasn't a possibility really, and it wasn't a viable option."

Fraser caveats that admission by explaining that Villeneuve would likely be against the idea of using LED displays on Dune even if the option were available to him at the time.

"I will say that I think Denis wanted this film to be more tactile than we could ever have possibly achieved using LEDs. He wanted to shoot for real. So what did we do? We went to Abu Dhabi. We got up at 3am. We went out to the desert as the sun was rising, we shot the scene, and then we left and came back at sunset. So I think that was the difference between [the two methods] – that tactility which occurs when you're really getting sand in your mouth."

At this point, it'd be remiss of us if we didn't ask Fraser which style of filmmaking he prefers.

"Of course, shooting in the desert is always tricky," he admits. "It takes a very determined director and determined actors. But I have a strong counter argument to that because sometimes it's easier visually.

"Yes, technically you could say, 'I'm lucky to have a really nice afternoon soundstage in what appears to be the desert.' Instead, I'm in the actual desert getting sand inside my boots, but what you end up with is something a lot more real and tangible.

"I worked so hard on The Mandalorian, because sometimes it's just not possible to shoot the way we did [on Dune]. But my preference? I just told you."

It's abundantly clear, then, that for filmmakers like Fraser, Vermette and Lambert, Dune proved a challenging but immensely fulfilling creative experience.

Villeneuve's approach to bringing his longtime vision to life combined traditional filmmaking methods with innovative, boundary-pushing techniques that have left a marker in the sand for generations of directors to come. That saying about films being for the filmmakers? Dune fits tidily into that category.

As for the now green-lit sequel, we couldn’t let three of the team who may (*wink*) be returning for Dune: Part Two leave without a word on what audiences can expect from Villeneuve's even-more-highly-anticipated follow-up.

All three remain tight-lipped, and only Vermette obliges with a wry smile.

"There's going to be a lot of sand. And sandworms." You heard it here first, folks.

Axel is TechRadar's Phones Editor, reporting on everything from the latest Apple developments to newest AI breakthroughs as part of the site's Mobile Computing vertical. Having previously written for publications including Esquire and FourFourTwo, Axel is well-versed in the applications of technology beyond the desktop, and his coverage extends from general reporting and analysis to in-depth interviews and opinion.

Axel studied for a degree in English Literature at the University of Warwick before joining TechRadar in 2020, where he earned an NCTJ qualification as part of the company’s inaugural digital training scheme.