How Linux is changing lives in Zambia

Helping a small village to connect and communicate

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Elton Munguya is the 28-year-old unit director of a moderately large residential and business ISP and network service provider.

His organisation counts many important institutions among its customers: the local bank, a hospital, several primary and secondary schools, the offices of the water administration board, a college and a bunch of cyber cafes.

The network has around 100 major nodes and access points (the exact number varies) and covers a geographical area of approximately 20km2.

Elton's role includes managing the roll-out of similar installations at other sites around the country. Like many young IT professionals, Munguya is laid-back, likeable and helpful to a fault. He's just bought his first car and he plans to get married early this year.

Nothing unusual so far, you might think. Except that Elton works for LinkNet Zambia. His 'patch' is a small rural village called Macha in the south of the country. The nearest tarmacked road is more than 15km away, and it's a 45-minute drive to get to the closest town, Choma.

Up until Chinese construction workers built the road to Choma a couple of years ago, the drive was an uncomfortable three-hour journey in a well-equipped 4x4. During the summer months, when it rains, the track into Macha itself is quickly rutted and virtually impassable by car.

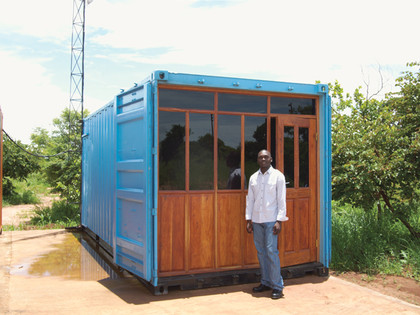

The local bank and cyber cafes are built into old shipping containers, originally used to transport donations of used computers from overseas. Rather than dump the containers unceremoniously in the bush, wily technicians turned them into secure, dry shared computing spaces.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Packing crates become shelving, and giant antennae are stuck on the roof to connect these sites with the satellite uplink at MachaWorks, the parent organisation of LinkNet.

The wireless networking is done using standard Wi-Fi kit. An omni-directional high-gain antenna on top of a water tower blankets a 3km radius at the heart of Macha with network signal, while beyond that directional antennas extend the range point to point.

Wireless is preferred since it's easier to deploy and less vulnerable to damage from lightning. Plus second-hand 802.11g routers are easy to get hold of.

Ubuntu inside

And the whole project is powered almost exclusively by Linux. There's even an Ubuntu Campus for the small technology training college, named in honour of a certain popular distribution and the ideal behind the name.

Most of us have used Linux to revitalise an old computer. Elton and the team at MachaWorks are doing the same thing: but instead of setting up a media server for the lounge or to complete Folding@Home tasks, they're evolving a way of working that's widely regarded as a role model for international development.

"The obvious reason we use Linux and open source wherever we can is that it's free; we can't afford software like Windows," Munguya explains. "But it's also faster than Windows on the PCs we use in our tests, and we find it easier to maintain; we don't have to worry so much about viruses when people use the PCs online."

Reliability is important. For a European customer, getting software support from an overseas call centre belonging to one of the big proprietary development houses might feel like a trial by telephone. Sending technicians out to a cybercafe that's 35km deeper in the bush because a customer opened the wrong email attachment is more than just costly and time consuming - it might not happen for weeks.

Munguya's story is quite extraordinary. The second of three brothers born in Mukinge in the north western province of Zambia, his father - a local pastor - died when he was just two. Despite being a single parent in a poor community where the main economic activity is subsistence farming, his mother made sure he and his brothers finished secondary school, after which he moved to the capital, Lusaka, for a couple of years to train in accountancy.

Unable to find a job in the city, he moved back to Mukinge at the end of 2006, just before LinkNet chose the village as its first site for expansion beyond its Macha base.

Going Dutch

MachaWorks itself was founded in 2001 by Gertjan van Stam, a Dutch engineer whose wife took a job researching malaria medicines at Macha hospital. The philosophy behind the organisation has been to train and employ local people wherever possible, to the extent that van Stam himself is the only foreign-born employee and takes little part in the decision-making processes.

What van Stam has, however, is an exceptional eye for talent and getting the right people to work with him. Elton was recruited as a potential administrator for the Mukinge network, and trained at the LinkNet Technology Information Academy (LITA) on Ubuntu Campus. Once he arrived at Macha, however, he decided he wanted to stay and help at the heart of the organisation.

MachaWorks isn't primarily about taking technology into poor, rural areas - there are many ICT4D (ICT for Development) projects that have failed because they put that mission first. Rather, it bills itself as a community-led, grassroots development NGO, which now has eight projects underway around Zambia.

LinkNet is only a part of what it does, and it takes a 'holistic' approach to development. MachaWorks has been responsible for building schools, medical centres and helping people from incredibly poor backgrounds to organise and find solutions to developmental problems for themselves.

Information and technology is at the heart of its work, however. The core philosophy is ground-up development - giving people the tools and the training to help themselves - that means establishing radio stations, TV channels and cyber cafes so that rural farms gain access to information, communication and collaboration.

At Macha, the community radio station and MachaTV are Linux-powered, too. Audacity is used for editing broadcast clips and interviews with local residents, health workers and officials, while magazine articles for TV shows are edited in OpenShot.

In a country with low literacy rates, where the AIDS/HIV epidemic has reduced life expectancy to 39, dissemination of information - on condom use, how to take medicines and so on - can literally be the difference between life and death. Because televisions and electricity are fairly scarce around Macha, one of the most effective ways to reach viewers is via YouTube (www.youtube.com/machabroadcasting) on a LinkNet workstation.

"With people who've used computers before," says Munguya, "we can train them to use Ubuntu to produce broadcast material in about a month. For those people who've never seen a computer, it can take up to a year."

The first thing that MachaWorks does with any new site, then, is install a satellite internet connection and a shipping container cyber cafe. Mobile network coverage is expanding rapidly throughout Africa, but the areas that LinkNet works in still tend to be off-grid for voice services, let alone GPRS or data.

The cyber cafes get used for all kinds of things: distance learning, organising transport to take crops across the country and buying cheap cars and other equipment online.