Inclusive innovation: designing a better future for everyone

The ultimate in digital assistants

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Our lives are led by, organized by, and drenched in, technology. But for a person with no major disabilities it’s easy to forget the needs of those who can’t see, hear or move quite as well as others.

Are today’s tech innovations ready for people with special requirements? And if not, why not? Let’s take a look at what’s going on in the areas of the smart home, VR and mobile tech in general for those with visual or hearing impairments.

How does the smart home work if you're deaf?

Smart speakers equipped with a voice assistant are naturally a great fit for those with a sight problem. They let people dictate messages, set timers and find out information without having to use a phone or any visual interface. Android and iOS may have ’select to speak’ accessibility modes, but a touchscreen is not the friendliest surface for blind people.

But what about the deaf or hard of hearing: can they use smart speakers? For the most part, they can’t easily. There’s little visual feedback on a standard smart speaker, and if you can’t hear the audio feedback, such a device is pretty useless.

Amazon has made real progress in this area, though. In July, it added ’Tap to Alexa’ features to its Echo Show, a smart speaker with a display.

Tap to Alexa offers a bunch of shortcuts for key features like the timer, weather, news headlines and the to-do list. And a virtual keyboard makes it easy to ask more involved questions.

This arguably turns the Show into more of a tablet, but it’s a welcome extra. Echo devices with a screen, the Show and Dot, also offer subtitles for Alexa replies.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

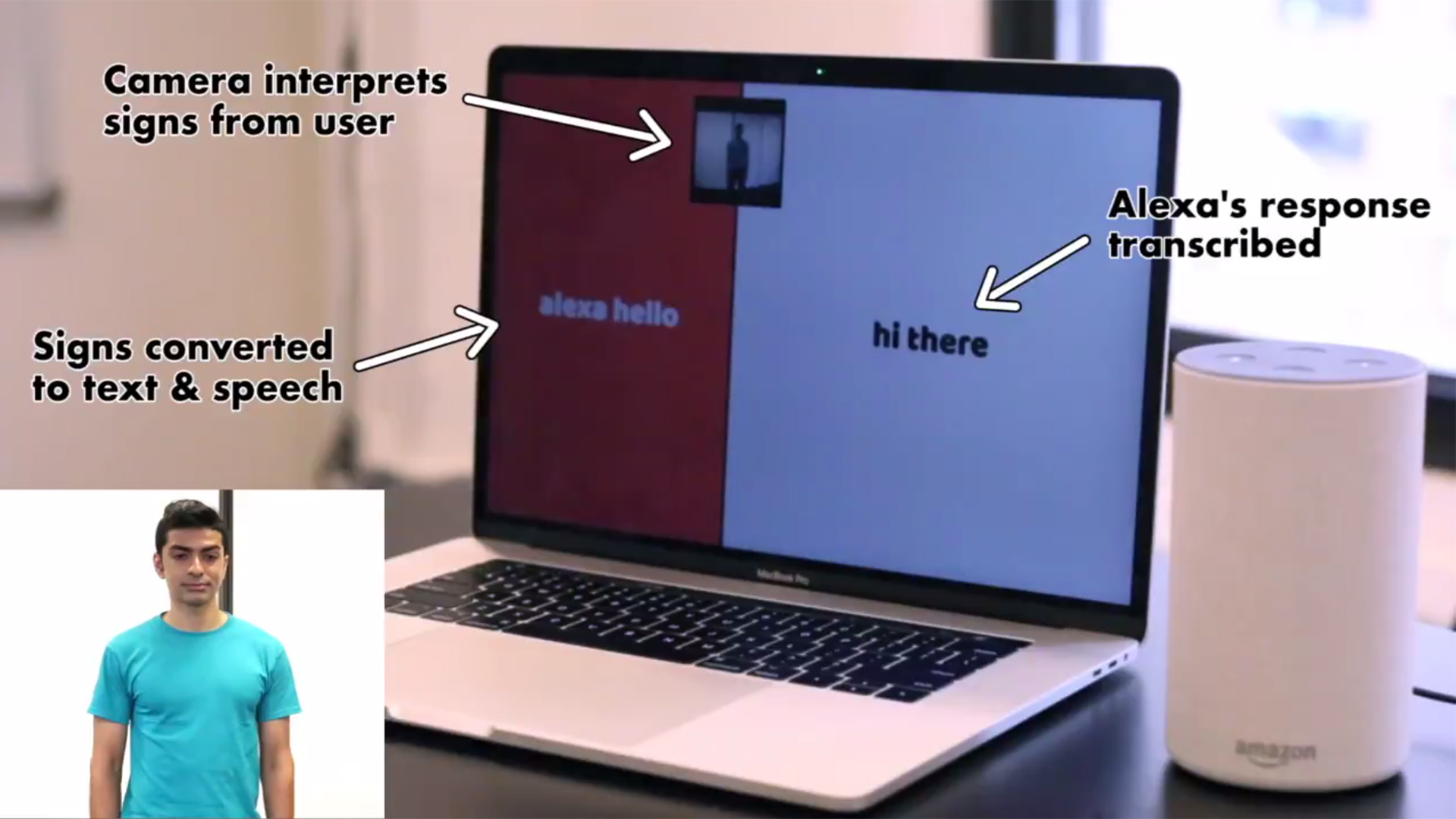

However, an independent developer has shown where Amazon should aim. Abhishek Singh designed a web app that recognizes sign language, and translates them into audio form for the Echo to understand.

When Alexa replies, the app then translates it into text, for the deaf person to read. It’s a very clever project, but largely a proof of concept.

Devising software that can reliably recognize the entirety of British and American language, is a huge challenge. But it would be an impressive addition to the Echo Show, or similar device.

Microsoft Research actually developed something similar in 2013 for its Kinect camera. It was an interface that both translated signs into text and audio, and spoken languages into signs, using an animated avatar. Kinect had particular benefits in this area, as its secondary depth camera made tracking articulated limbs in 3D space easier.

However, in recent years Microsoft’s attention turned from Kinect-based augmented reality to HoloLens and Windows Mixed Reality. It was, again, ultimately a proof of concept.

Can blind people use VR?

Virtual reality lies somewhere on the other side of the tech spectrum, as a more visual medium. Interestingly, there are reports VR can appear much clearer than the world outside with some sight conditions, including loss of central vision, tunnel vision and extreme near-sightedness.

This is a knock-on effect of the screen's proximity to your eyes – VR’s intention is to trick our brains into thinking objects are meters of miles away, when the screens are only a couple of inches from our eyes.

But what about blind people? Much like deaf people using a smart speaker, the initial assumption is: surely that won’t work. In most cases, it doesn’t. However, Microsoft developed a compelling VR use for blind people with the Canetroller.

This is a virtual white cane that's much more than just a VR remote stretched out to stick form. It attaches to a 'brake' worn around the user’s waist. This stops any horizontal movement when the stick hits a virtual object, and produces tactile feedback to simulate interaction with different surfaces.

Microsoft suggests this could be used to make people feel more confident when, for example, getting used to crossing the road, acting as a training ground for such real-world situations. However, it could also be used as a controller in other VR experiences.

Of course, it’s more likely that we won’t hear of the Canetroller again, as is often the fate of such research projects.

Hearing issues in VR initially seem less problematic. If you can see fine, you can at least experience the 3D and 1:1 motion tracking that makes virtual reality so immersive. However, there’s surprisingly little subtitle support in VR games, even though subtitles are pretty standard in conventional titles.

There’s a practical reason for this. Subtitles need to be situated in 3D space, and if they’re in the very near foreground their presence feels very distracting. Text like this works best if it’s merged with the environment, and that's a tougher problem than just plugging in movie subtitles.

The BBC’s R&D department conducted some tests to see which kind of non-advanced subtitles work best for its 360-degree VR content: titles that follow your view, do so with a delay, those that stay in place in the scene or are repeated in the scene as you turn – it found simple titles that follow your head movements work best.

What are the recent accessibility innovations?

There’s work to be done in the smart home and VR tech to make these frontline fields more inclusive. However some companies that use related technologies do focus entirely on the deaf and partially sighted.

Oxsight is an augmented reality headset that can improve sight for those with limited vision. It has cameras on its front, and their view of the world is passed through one of six filters before being displayed on the VR headset-style OLED panels inside.

Most of these filters radically increase contrast, with some simmering the image down to white outlines on a black background; others limit the colors in the scene. The headset is attached to a control box, which allows the user change the mode on the fly.

Oxsight modifies the tech of Epson’s video glasses for a specific purpose, to make the most of what vision the wearer has.

Conversely, hard-of-hearing gadget SpeakSee borrows some of the tech inside smart speakers, namely microphones with beamforming.

SpeakSee is a set of clip-on microphones that connect to a phone or tablet over Bluetooth. Each person in a conversation wears one. Beamforming lets each mic listen to just the person wearing the mic, not ambient noise or anyone else talking at the same time.

What you end up with is a written transcription of the conversation on the connected phone, with each person’s chat shown in a colored speech bubble, just like a group chat. It’s richer than the average speech-to text app. SpeakSee was funded on IndieGoGo in July 2018, earning over $150,000.

For now at least, it seems small projects and startups are providing more innovative accessibility solutions than the big names of tech. Let’s hope that, as emerging tech areas like the smart home mature, they catch up.

TechRadar's Next Up series is brought to you in association with Honor

Andrew is a freelance journalist and has been writing and editing for some of the UK's top tech and lifestyle publications including TrustedReviews, Stuff, T3, TechRadar, Lifehacker and others.