Will 2018 be the year the download officially dies?

When was the last time you downloaded an MP3? If you're one of the legions of subscribers to streaming platforms like Spotify, Tidal and Apple Music, rumors about the death of the download probably won't bother you one bit.

Digital Music News reports that Apple, the company that was key in legitimizing downloaded music with its iTunes service, is set to kill it off.

Sources within Apple suggest that the timeline for phasing out downloads is being brought forward, and that they could cease within a year (the original plan, apparently, was two years).

With streaming services like Spotify, Deezer, Apple Music, Rhapsody, YouTube and Tidal all the rage, are we now in the death throes of the download?

How significant is the downloaded music market?

Compared to streaming, the downloads market is small. The Nielsen Music U.S. Mid-Year Report of July 2017 revealed that on-demand audio streams reached over 184 billion streams in the US in the first half of 2017, a 62.4% increase over the same time period in 2016.

“The first half of 2017 has seen some incredible new benchmarks for the music industry,” said David Bakula, SVP of Music Industry Insights at Nielsen. “The rapid adoption of streaming platforms by consumers has generated engagement with music on a scale that we’ve never seen before.”

Crucially, Nielsen also reported an 18.3% decrease in album downloads, and a 24% decrease in digital track downloads.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

That's a market that's crashing. "Just five years ago, downloads accounted for 70% of global digital music revenues while streaming was only responsible for 18% – and now that ratio is reversed," says Sergey Bludov, SVP Media and Entertainment at DataArt.

"Virtually every aspect of the music industry has undergone a profound transformation over the past 20 years, and one of the most significant changes occurred in the distribution of music, shifting from physical mediums to a digital-first reality."

It’s simple: downloads are dying.

Where does this leave lossless music?

The music industry would love for Hi-Res Audio and lossless music – a premium product whose large file sizes make streaming impractical – to become popular.

"I think it's overrated," says Gareth Emery, an English electronic dance music producer and DJ. "I'd be very surprised if more than 100 people can tell the difference between a well-encoded 320kbps MP3 file and the source WAV file."

There are other problems; not all software is compatible with all lossless audio file formats, and few headphones currently on sale truly support Hi-Res quality.

"As the hardware and network capabilities gradually catch up with the new music formats, there’s a chance that Hi-Res will become a next stage of the audio evolution in a natural way," says Bludov.

"For now, it’s simply too early for the lossless/Hi-Res Audio format to make a real impact on the music ecosystem."

Is streaming any good for artists?

No. "It's great value for the consumer, but it's terrible for artists, who are only on there because there is no better alternative," says Emery, who has a couple of million listeners per month on Spotify.

"It's not possible for record producers to make a living, and I make less than 1% of my income from Spotify – and it takes over a year to get paid for a stream."

Spotify was supposed to disrupt the major labels, and allow artists to release music direct to consumers and receive direct payment.

"Instead, they sold out to major labels by striking a bunch of really restrictive deals early on to get the rights to use their catalog, so labels make a lot of money, and so does Spotify, but the artists get screwed," says Emery.

He wants to change that by launching a new streaming platform called Choon in 2018, which will cut out the middlemen. The system will use Ethereum, which has the capability to write smart contracts into the blockchain that are automatically executed when specific conditions are met, such as a music track being played.

"Artists will get cryptocurrency tokens for each listen of their track, and earn a hundred times more than on streaming services," he says.

Will Apple really stop selling downloads?

Apple has always been a company that prides itself on taking ‘courageous’ decisions. "It wouldn't surprise me if Apple [dropped the download] because it has form in cutting stuff way too early without having a better plan in place, the classic example being the headphone jack on the iPhone 7 - what an absolutely terrible decision that was," says Emery.

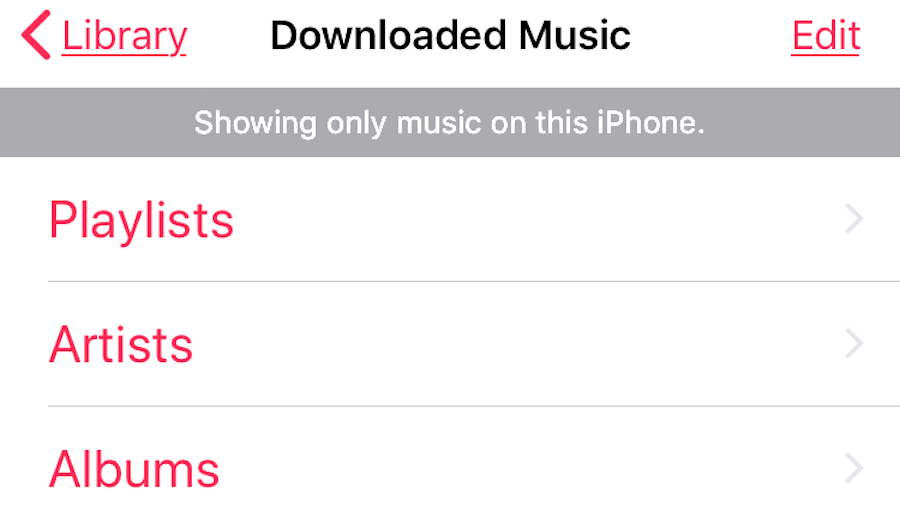

Apple ought to be careful because, for now, it has something Spotify doesn't. The integration of Apple Music into an already bloated iTunes may have made the platform hard to use, but Apple does at least sell DRM-free MP3s that can be downloaded and used freely away from a walled garden.

"Spotify has it mostly right, but the only issue is you can't do anything else with the music, so as a DJ I find it completely useless – everything is stuck in the walled garden of Spotify," says Emery.

So the move from downloads to streaming isn’t so much about changing formats, but about consumers being trapped within one service’s walled garden.

When will we see downloaded music disappear?

Although Apple is rumored to want to cease offering digital downloads of music within the next year or so, that could be unwise for purely commercial reasons.

"Even though digital music has surpassed the physical sales, pushing people into streaming by eliminating the choice may have a very contrary result," says Bludov. "Users may defect to stream-ripping sites, and thus the move will play into the hands of pirates."

Although Apple may be considering the move as a publicity stunt to give a boost to Apple Music, it's unlikely that downloaded music will disappear across the board while demand exists.

"Most streaming services also offer downloads as a premium option for subscribers," says Bludov, and there's another sector of the community that has no option but to download, rather than stream: frequent flyers.

The importance of mobile networks

For people who listen to music somewhere with a stable LTE or Wi-Fi connection, there's no need to download.

"Within a decade, we will definitely see the end of downloads, but I do think it will take that long because these technologies do tend to stick around until the slowest people in the back of the pack are able to migrate," says Emery.

He stresses that only when the mobile networks get to a point where users can do anything they want, and there's reception everywhere, will the need to download music completely cease.

"Like the way vinyl still exists, so will downloads for those who need them, but it will be a tiny sliver of a big pie," says Emery. "For most people the tide has been turning for a few years."

Downloading from streaming services to listen to offline (and, crucially, only within a streaming app) will likely remain an option for a long time.

However, with streaming-friendly 4G networks on the rise, and 5G imminent, the days of downloading an MP3 to do with what you want are surely now coming to a close.

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),