Why bots taking over (some) journalism could be a good thing

Automation isn't the enemy of serious reporting

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Sometimes it’s easy to be cynical. When I read pieces suggesting that in the future robots will do all the journalism, I wonder: hasn’t that already happened? My news feeds are full of pieces highlighting the funny tweets I saw yesterday, regurgitating press releases and embedding YouTube clips of someone I don’t recognize being 'totally destroyed!' by someone I haven’t heard of. You could probably automate that in an afternoon.

We’re already used to news aggregation, where algorithms create personalized feeds. Could the next step to be automated writing?

- Do you have a brilliant idea for the next great tech innovation? Enter our Tech Innovation for the Future competition and you could win up to £10,000!

Shallow isn’t stupid

Not so fast, bots. Buzzfeed does some brilliant, important journalism, as do many other media properties that also publish the shallow stuff. In our ad-driven utopia, in which hardly anybody wants to pay for news any more, the fluff is often what pays the bills, and it's bankrolling the good stuff, because good journalism takes time, effort and money; what’s important is rarely what’s bringing in the eyeballs for advertisers.

Article continues below

If robots can take over the grunt work, which in many cases they can, then that has the potential to lower media organizations’ costs and enable them to spend a greater proportion of their advertising income on more serious material. That’s terrible news for anybody whose current job is to trawl Twitter for slightly smutty tweets by reality TV show contestants, but great news for organizations funding the likes of Guardian journalist Carole Cadwalladr, who broke the Facebook / Cambridge Analytica scandal. Isn’t it?

What newsbots can (and can’t) do

A lot of journalism is simple reporting: it simply says, “here is a thing that happened”. And that can be very valuable.

When the UK's Met Office issues a weather warning, that’s crucial information for farmers. When a company issues a trading warning or central banks consider raising interest rates, that’s important for the financial markets. When a publication in one part of the world publishes a story, it might be really useful information for organizations in another part of the world, and so on. Automating that kind of thing is pretty straightforward, so for example a bot might take a company’s financial press release and summarize it for a financial news site.

Technology can help with a lot of basic reporting. For example, the UK Press Association’s Radar project (Reporters And Data And Robots) aims to automate a lot of local news reporting by pulling information from government agencies, local authorities and the police. It’ll still be overseen by “skilled human journalists”, at least for the foreseeable future, but the actual writing will be automated: it uses a technology called Natural Language Generation, or NLG for short. Think Siri, Alexa or the recent Google Duplex demos that mimic human speech, but dedicated to writing rather than speaking.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

According to Urbs Media editor-in-chief Gary Rogers, who’s working with PA on the RADAR project, “local papers don’t have the staff to write those stories and no centralized operation – even at the scale of PA – is going to take on writing 250 localized stories. We realized if we can write this automation into the local news production process, we are not taking someone’s job, we are doing something that no one else is doing.”

Tools of the trade

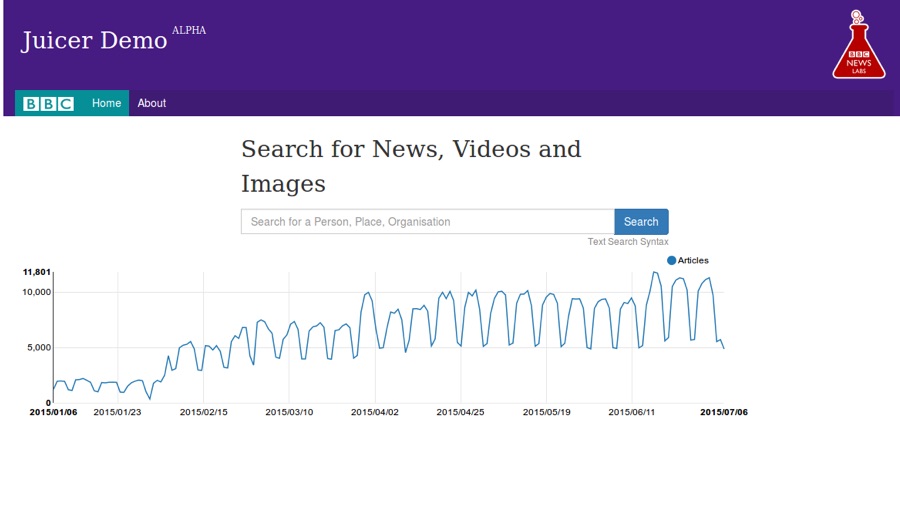

Where automation gets interesting is when it assists journalists rather than replaces them. The BBC’s Juicer “takes articles from the BBC and other news sites, automatically parses them and tags them with related DBpedia entities. The entities are grouped in four categories: people, places, organizations and things (everything that doesn’t fall in the first three).”

The New York Times’ Editor app, meanwhile, scans, classifies and tags articles to crunch data faster than humans can. The Washington Post’s Knowledge Map assists readers by linking related content together, automatically “providing relevant background, additional information or answers to frequently asked questions, when the reader wants it”.

Fighting the fakes

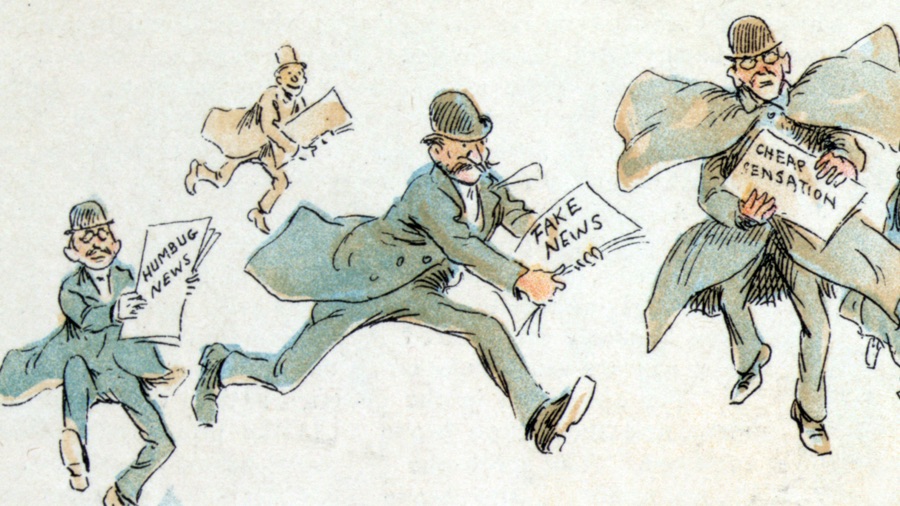

My biggest worry about artificial intelligence writing stories is that if you put garbage in, you get garbage out. Despite its supposed battle against fake news, Facebook has been loath to exclude the political site InfoWars from its platform – even though InfoWars has variously reported that the horrific Sandy Hook massacre of schoolchildren was a hoax and that NASA has a slave platform on Mars. Over on YouTube, the trending topics algorithm often prioritizes tinfoil-hat nonsense over verifiable fact; on Twitter, we’ve seen the rise of bots endlessly posting the same often baseless claims. An AI that sees such sources as credible is an AI that promotes fake news rather than fights it.

And of course fake news has very real consequences, whether it’s hoaxes causing real-world violence or quackery and pseudoscience resurrecting deadly diseases we thought we’d got rid of for good.

Fighting fire with fire

The answer may be more AI. For example, the startup AdVerif.ai uses AI to detect fake news and other problematic content on behalf of advertisers who don’t want their ads to appear next to made-up content. It describes itself as “like PageRank for fake news, leveraging knowledge from the web with deep learning”. In practice that means checking not just the page content but the trustworthiness of its publisher, and comparing it with a database of known fake news articles. It’s in its very early stages, and mistakes do get through, but it and systems like it have the potential to help us separate fact from fiction.

Then again, as the internet has demonstrated time after time, the bad guys find ways to use technology too, and they often outsmart the good guys. It isn’t hard to imagine a not-too-distant future where one set of AIs battle fake news while another set comes up with ever more inventive ways to battle the first bunch of AIs.

Could AI lead to an online arms race between fakebots and newsbots like the one between advertisers and ad-blockers? My optimistic side says no, but two and a half decades spent online tells me yes.

Maybe I should ask Siri to investigate.

TechRadar's Next Up series is brought to you in association with Honor

Contributor

Writer, broadcaster, musician and kitchen gadget obsessive Carrie Marshall has been writing about tech since 1998, contributing sage advice and odd opinions to all kinds of magazines and websites as well as writing more than twenty books. Her latest, a love letter to music titled Small Town Joy, is on sale now. She is the singer in spectacularly obscure Glaswegian rock band Unquiet Mind.