Autonomous tech vs the professional rally driver

Goodwood Festival of Speed is the place to be if you’re into cars and tech. The huge event in West Sussex has evolved a lot over the 25 years of its existence too, much like the vehicles it showcases. While a lot of those creations are from yesteryear, FOS always features the latest in cutting edge technology, some of which could be found in the Goodwood Festival of Speed Future Lab for 2018. Inside there you could also enjoy a virtual reality autonomous trip, but we managed to go one better and experience the real thing.

This year, as part of the 25th FOS anniversary celebrations, Siemens came up with a cool idea by fitting out a 1965 Ford Mustang with all the kit to make it a fully self-driving car. Mention autonomous cars to a lot of people and they automatically seem to lump them into the same category as electric vehicles. So this experiment was a neat twist, because it combined old school classic engineering with bang-up-to-date technology to illustrate that autonomy can work on pretty much any level and using any kind of vehicle.

Passion for power

However, not everyone likes the thought of not being able to actually drive; being behind the wheel and in control is something lots of us love to do. Driving is also a living for many; like for professional rally driver Mads Østberg from the Citroën Total Abu Dhabi World Rally Team, who were also at FOS. So with an old classic like the Mustang finding its way around without a driver, should Mads be worried about being replaced by a collection of black boxes and a laptop in the future? Earlier that day when we saw him in action that seemed pretty unlikely. The way this guy threw his Citroen C3 around the Forest Rally Stage at FOS was awe-inspiring.

For good measure, we got a lap around the Forest Rally Stage at the top of the Goodwood estate and based on that it was pretty clear that any autonomous car – let alone a 53-year-old Ford Mustang - wouldn’t be able to get anywhere near the razor-sharp reaction times of a living, breathing human like Mads. The course was just too hairy and unpredictable for anything ‘programmed’ to handle. Rally ace Mads, on the other hand, had been around it so many times he knew every gnarly bit of flint under the tyres.

The cars were certainly very different too. The Citroen C3 was a full-on, bang-up-to-date rally car. The other was a pretty clean though slightly tired vintage Pony car. The Citroen had a revvy 1.6-litre turbocharged four cylinder engine and four-wheel drive, the Mustang a 289 Cubic Inch V8, which equates to, er, 4.7-litres. The former had a whole crew of mechanics working night and day, tuning, tweaking and rebuilding where necessary. The Mustang had the enthusiastic staff and students from Cranfield University, who’d beefed up the old timer with electronic ignition, but it was essentially bog-stock standard.

There was even the original owner’s manual in the glovebox of the Mustang. And, weirdly, the team had managed to find an example that matches the Siemens colour palette, including the interior trim. It was very snug inside, but then again so was the Citroen. And the Citroen doesn’t have any glovebox. In fact, the latter was actually borderline claustrophic, because you’re strapped in so tight, within the confines of a moulded racing seat while the roll cage enveloped you from every angle. And you couldn’t see an awful lot either. Whereas sitting in the Mustang with the window down you could see plenty and enjoy a whiff of fresh air too.

Going old school

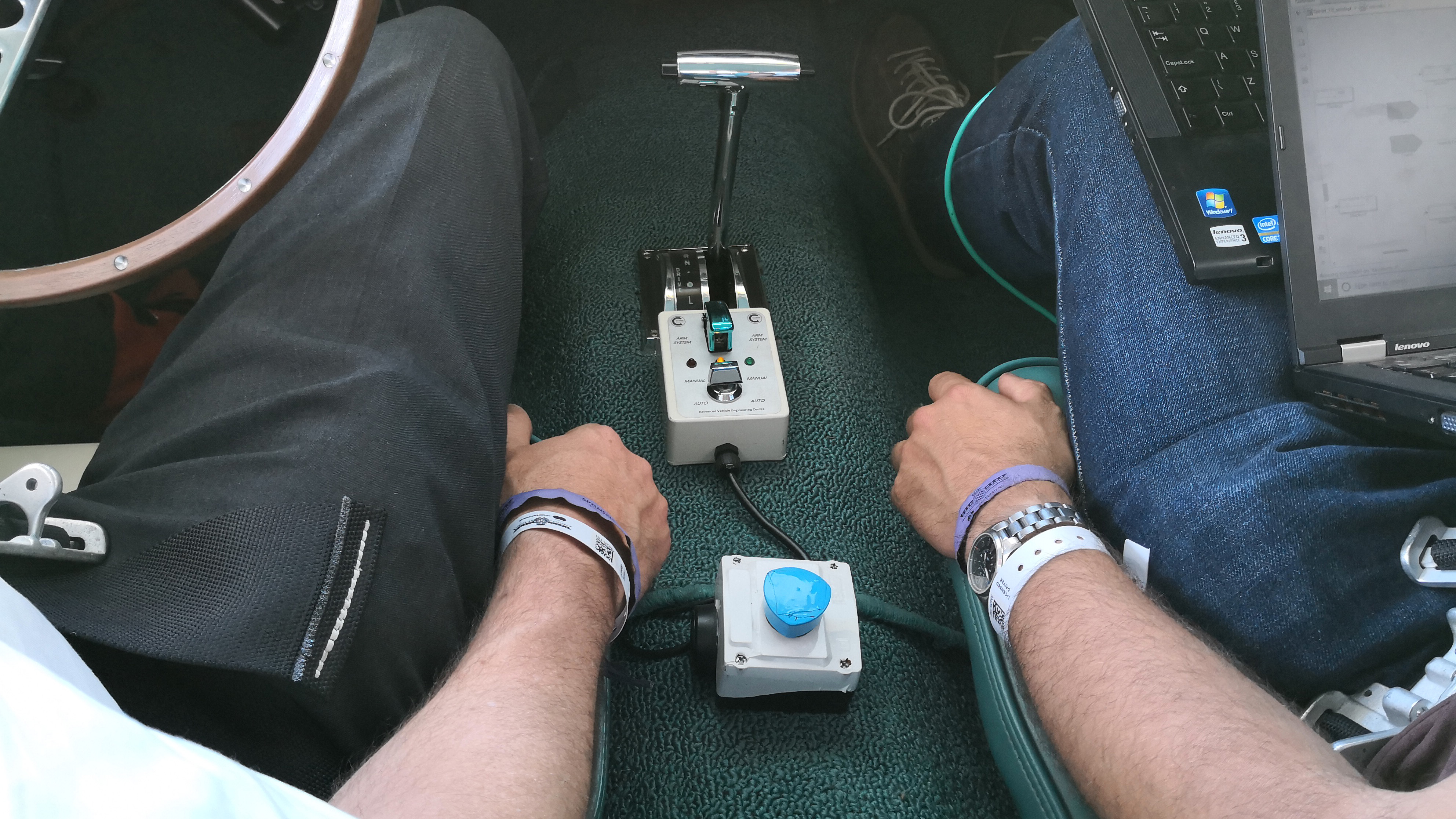

So, with the run with Mads and the Citroen C3 out of the way it was time to see what sort of a job the gas-guzzling autonomous Ford could do with its tech-laden team on board. In the front of the Mustang, there was ‘non-driver’ Dr James Brighton, senior lecturer at Cranfield University who piloted the car when it was running normally. To his right – the car was a left-hooker – Dr Kim Blackburn, a Research Fellow also from Cranfield with a pair of laptops on his knees. It was hot as there was no air-con, but aside from that it was pretty cosy sitting in the back alongside James Cottle, a recent graduate at Siemens.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Eventually we got the nod to go for it and James fired up the V8. Getting out of the parking area and down to the start line was done manually and the straight through exhaust pipes let people know we were coming through. But could an autonomous 1965 Ford Mustang without a driver instill the same feeling of faith in me as Mads did earlier when we went around the rally circuit?

Well, the ‘hands-free’ 1.86 kilometre drive up the hill was more leisurely but trouble free. On the Thursday before some of the press had tried to make a mountain out of a molehill after the Mustang had veered off-track and brushed a hay bale. The hairline scuff on the tip of the front wing was barely noticeable and, it seems, the issue was pretty minor considering the limited development time the team had. Of course, up near the flint wall towards the top of the track they dropped the speed off a little, but we reached the peak unscathed.

So what’s needed to do this job when you don’t have a Mads in the driver’s seat? In the case of the Siemens Ford Mustang it’s a combination of technology that included a suite of sensors and control algorithms. Plus, naturally, a human element, in the shape of those staff and students from Cranfield. The academics were the same people who were involved in creating a full-size radio control Nissan GTR a while back, so they knew what they were doing. However, that was working with a state-of-the-art modern car. Had it been different with an elderly Ford Mustang?

Innovative engineering

“In terms of some bits of it then yes, there are similarities, but none of the boxes are the same,” said Kim while picking through another screen full of data. “There are general strategies in terms of actuators, which take position commands. In the case of the GTR the position commands came over a radio link via the radio control, whereas here they come via an autonomous system. But of course, this is Goodwood, so you’ve got to bring proper cars; you can’t just turn up in anything. So we wanted something that would appeal to the car enthusiast. We’ve had a load of people along who say ‘so you’ve electrified it?’ There is this belief out there that autonomous cars are electric.

“The point is that autonomy is another technology in the same way that cruise control, pneumatic tyres and paint are also automotive technologies. We’re saying the future can be interesting and yes, there is a role for a pod that gets you home, with no steering wheel and no intervention needed from you at three in the morning when you’ve had one too many.

"There’s also a role for autonomy as a driver aid like for motorway driving and also a role, potentially, in motorsport. If you’ve just bought your new BMW, Porsche or Ferrari and you want to drive it on the track – perhaps if you’re a businessman and you don’t want to admit that you can’t drive – you can have an autonomous race mode that when you do a lap it’ll help you through all those corners. Rather than studying a map you actually learn using the autonomous system. It’s like having a driver alongside you.”

“What we’re saying is, this is a Goodwood crowd, they like cars, they like the idea of being able to put it back into manual mode and have fun, and autonomy is not the end of fun with cars. So it’s a ‘because we can project’ where we’ve taken things that we’ve had on the bench at the university and taken a team of staff and students who wrote 95% of the code for this and thought ‘where could we go with it?’ Getting an autonomous Mustang up the hill at Goodwood, which is a particularly challenging track for a number of reasons, is one thing but it’s all about getting people interested in engineering too of course.”

In the boot, or perhaps we should say trunk seeing as it’s a Mustang, there was a whole bundle of technology. It was needed too, as the team didn’t have long to prepare for the challenge and it was a tricky route to navigate. Central to the car going in the right direction were the actuators and algorithms. “If you think of levels of autonomy, there’s the actuators, which are used to control the automation rather than the autonomy,” said Kim. “Then there’s the path following algorithm, which makes sure the car goes where it’s supposed to. On top of that there’s the path planning algorithm that tells you where to go.”

Smart thinking

The Citroen C3 WRC used plenty of tech and innovative materials, but it was as much about the driver that made things work so well. Granted, the autonomous Mustang was plodding along compared to the high-speed antics of the little Citroen C3, but in a lot of ways it was a good feeling knowing you were in the capable hands of a professional rally driver who knew the circuit inside out, even if he spent most of the time going full-tilt. You just can’t get a computer to feel that in the same way as a human, but the Mustang still did a fine job of driving itself, albeit a lot less frenetically.

I guess what we learned from this tech challenge is that, ultimately, there’s room for both human interaction and computing power in the future. Autonomous vehicles could help take away the drudgery of dull commutes, or tiring motorway trips that offer little in the way of excitement. But, it’s good to know that when a decent stretch of tarmac reveals itself around a bend, we’ll still be able to press the ‘off’ button, put the throttle down and just drive. Hopefully…

Rob Clymo has been a tech journalist for more years than he can actually remember, having started out in the wacky world of print magazines before discovering the power of the internet. Since he's been all-digital he has run the Innovation channel during a few years at Microsoft as well as turning out regular news, reviews, features and other content for the likes of TechRadar, TechRadar Pro, Tom's Guide, Fit&Well, Gizmodo, Shortlist, Automotive Interiors World, Automotive Testing Technology International, Future of Transportation and Electric & Hybrid Vehicle Technology International. In the rare moments he's not working he's usually out and about on one of numerous e-bikes in his collection.