Don't make the same dangerous rookie running mistake that I just did

I didn’t hydrate properly, and I felt the consequences

Beginner runners get plenty of advice when starting their fitness journey, almost all of it sound and sensible. Warm up first with some dynamic stretches. Start slow, taking regular walking breaks if you need to. Choose the best running shoes. Wear a good running watch (not just any will do, as I found out when I tested the cheapest fitness tracker against a top Garmin watch). The other one is “make sure you hydrate”; and it’s advice that I, someone who writes about fitness for a living, shamefully neglected when running a half-marathon recently.

To start with, it’s worth emphasizing that I hadn’t signed up for an official half-marathon. This was a practice run ahead of my first ever full marathon, the Brighton Marathon event scheduled to take place on April 2. I’ve been doing progressively longer runs for the last five weeks, and I just crested the half-mara mark. Well, almost – by the time I arrived back at my front door, I was 0.4km shy of a ‘true’ half marathon. But who’s counting?

Because it was a training run, there was none of the usual support that’s around when you run a ‘real’ half-marathon, such as stalls with cups of water, or bottles of energy drink, or sachets of carbohydrate gels. It was just me out there, running in the rain with two small bags of Haribo sweets to keep my blood sugar up - but I didn’t take a bottle of water, nor were the sweets really enough to compensate for the energy spent.

Some marathoners recommend driving to key points along your route and stashing bottles of energy drink or water somewhere out of sight. If you're running on a treadmill (which I've only just taken to, even though I'm a die-hard outdoor runner) it's easy to keep all the stuff by the tread. I didn’t do any of the above, nor did I take a specialist bladder of water in a running bag. I drank one glass of water before the run, and ran the route dry.

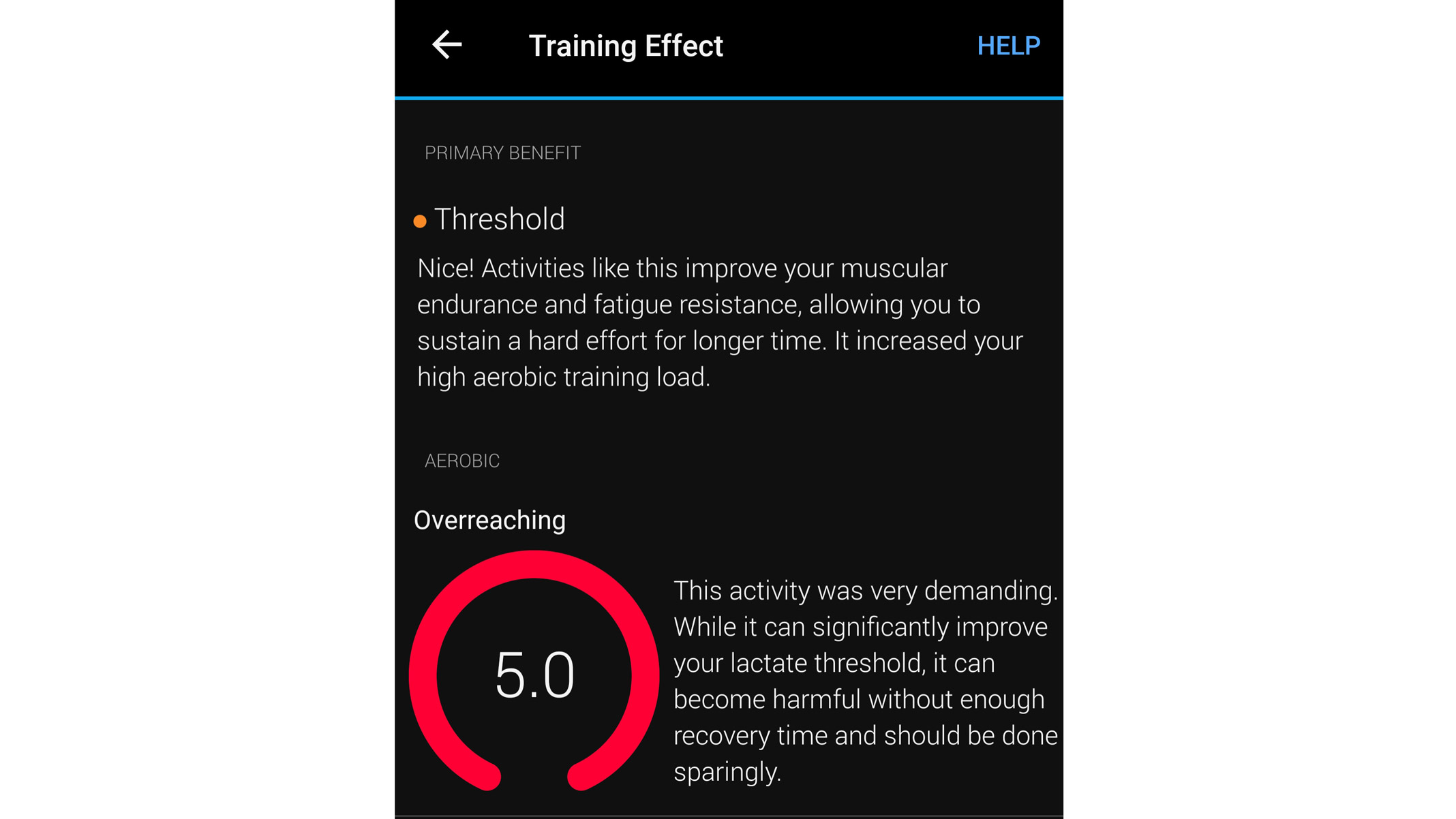

My Garmin watch estimated the aerobic training effect to be 5/5, a ‘very demanding’ workout that burned 1,575 calories. When I got in, I drank a glass of water straight away, ate a big lunch (a foot-long falafel and halloumi wrap from an awesome local place), and considered the matter closed.

Boy, was I wrong. My Garmin also told me, ‘while [this workout] can significantly improve your lactate threshold, it can become harmful without enough recovery’. Proper hydration and fueling is part of that recovery.

A report about long-distance running and hydration, published by sports scientists from the University of Alabama, states that “large body water losses can lead to dehydration (known to impair cognitive function) and are associated with increased risk of heat illness and decreased aerobic performance,” in athletes. The report goes on to say that “compounding the potential negative effects of dehydration is the fact that running is often a solitary endeavor, and the athlete may be alone and far from support when dehydration occurs.”

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

The symptoms of dehydration, and presumably my dip in blood sugar, didn’t set in until that evening, when I began experiencing a headache that got more painful during the night. By 6am the following morning, I was shivering in my bed, the headache had gotten even worse, and I was sipping water with trembling hands, waiting for the painkillers to kick in so that I could go back to sleep.

It then occurred to me that I had taken no water with me on a 13-mile run, and that I was lucky it was a cold day in January. If it had been a few degrees warmer and sunnier, I might have begun experiencing dehydration on the run itself – and my route took me away from busy London streets and into quiet parks for long stretches.

I learned an extremely valuable lesson: hydration and recovery are key if you’re going to exert yourself for longer periods than you’re used to. This is important, whether you’re walking to hit your step count for the day, or putting in miles on the bike.

For most conventional exercise that lasts up to an hour, a bottle of water will do the trick just fine, as long as you drink more after your sweat session, but extreme exertion lasting multiple hours may require added electrolytes from a sports drink or tablet which can be mixed with water. These added electrolytes can help your body process the water more efficiently.

However, according to research, I’ll need to be careful not to drink too much water on race day, less I fall foul of exercise-induced hyponatremia (low sodium levels). Retaining too much fluid in my body could cause my sodium levels to drop, according to a University of Virginia publication.

For my next long run, along with some simple sugars, such as energy gels or sweets, I’ll be taking a hydration bladder in a running backpack with me to sip on at regular intervals, with an electrolyte tablet mixed in. Legendary ultrarunner Scott Jurek drinks only when he physically feels thirsty rather than sticking to a plan, but three or four long sips an hour is a good guideline according to research from the University of Connecticut.

So, next time you're pushing yourself to hit a new PB at home, in the gym, or on the road, make sure you're fueling properly and recovering well. I suffered so you don't have to.

Matt is TechRadar's expert on all things fitness, wellness and wearable tech.

A former staffer at Men's Health, he holds a Master's Degree in journalism from Cardiff and has written for brands like Runner's World, Women's Health, Men's Fitness, LiveScience and Fit&Well on everything fitness tech, exercise, nutrition and mental wellbeing.

Matt's a keen runner, ex-kickboxer, not averse to the odd yoga flow, and insists everyone should stretch every morning. When he’s not training or writing about health and fitness, he can be found reading doorstop-thick fantasy books with lots of fictional maps in them.