The Messaging Wars: Who gets to choose how we talk?

Everyone's fighting for a piece of the pie

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Communication is big business. Like Google with search and Facebook with social, it would be any company's dream to dominate the messaging space, but whether anyone can actually "win" this battle is uncertain.

Since the birth of the smartphone, people have relied less on traditional calls and text messages and more on other messaging services and apps. This increased demand has created a slew of apps, from companies big and small, that handle billions and billions of messages per day. The total volume of SMS messages sent daily is around 20 billion; at the start of last year WhatsApp, the messaging app owned by Facebook, said it had surpassed that with its users sending over 30 billion messages a day. Other chat apps, such as Kik, are also seeing phenomenal growth.

It isn't just teens who are using these services, either, as adults realise the potential of being able to quickly distribute a message to their friends, colleagues, or strangers. WhatsApp has seen a sharp uptake of users in the 30-54 age bracket, many of which are first-time users of social media and internet-based communications.

Snapchat, the American startup valued between $10 and $20 billion, now has 100 million daily active users, many of whom are under 20. Like Facebook, the service has captured the minds of teens who share tens of millions of photos, videos, drawings, and text-based messages per hour.

The enabling of communication, especially among people who would traditionally not have communicated in this way, is important to big companies like Facebook, which spent $20 billion on acquiring WhatsApp, itself now boasting over one billion users.

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg has said that WhatsApp is the "primary form of communication" for some countries, especially in Europe or Asia. The service recently dropped its annual fee in an effort to bring on more users, many of whom do not have a credit card, putting it into the hands of even more people.

The business model of "pure" communication - i.e. two or more people talking - is as-yet unclear, but Facebook, Snapchat, Line (a popular app in Asia), Kik, and others and others are trying to figure it out.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

WhatsApp recently broadened its focus to let users "communicate with businesses." How far it will go remains to be seen, but the company is clearly trying to monetise a vast, engaged user base.

Speak easy

Trends are appearing with various factions emerging. Facebook, for example, has built multiple communications products - Facebook Messenger, which has 800 million users, and the "big blue" app itself - alongside acquiring WhatsApp. Snapchat has grown its own business, rejecting a $3 billion acquisition offer from Facebook in the process, and Apple, with its iMessage service, processing several billion messages per day.

All of these companies, valued between $15 billion and $650 billion, are competing to own the communication that happens between users, but just look at the average person's collection of smartphone apps and you'll understand why there may never be one winner.

And still, while there's much potential in this space, there's no guarantee of success. Twitter has seen user growth stall in recent years as Facebook, WhatsApp, and other social networks flourish.

"There appears to be a consensus that the decline of Twitter usage is due to the increase of WhatsApp, especially amongst younger generations," says Jan van Vonno, a senior researcher for IDC. "Although I personally do not have the stats to back this up, I think there's no denying WhatsApp is replacing a lot of these Twitter conversations."

It was probably not WhatsApp's intent to go after Twitter - the two services appear to be very different - but then the iPhone and Instagram did not set out to kill Kodak, either.

Facebook's ambitions do not just stop at WhatsApp. The company recently unveiled a virtual assistant for Messenger that can, when asked, help with tasks, such as booking plane tickets or working out the best route to take.

This, Facebook reckons, is one of the ways messaging can be leveraged: as a hub for everything else. If all the user's activity happens within the walls of Messenger, then Facebook will essentially own the user's phone.

Facebook has not made it clear exactly how Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp will be differentiated (because, at their core, they are both apps that let a user talk to other people). However, a recent set of features for Messenger, including an AI and in-app apps, suggest the company is looking to build it out beyond just talking.

WhatsApp, however, still seems primarily focused on communication, especially in a lightweight, low-data-usage form. Since the acquisition last year, few new features have been added, although it's clear that WhatsApp sees potential in going after the Slack audience. This is a good opportunity to speculate on how Facebook will treat WhatsApp and Messenger differently.

The Snapchat generation

Snapchat, driven by its younger users, has also been growing exponentially. CEO Evan Spiegel, just 25 years old, was derided for not accepting a $3 billion buyout offer from Facebook. His company is now worth an estimate $15 billion and, according to market research, is one of the most popular apps among young people.

Initially slow to monetise, Snapchat is now experimenting with stickers, filters, and other brand-sponsored content. The company has raised over $1 billion in funding, however, giving it a long runway to find exactly the right way to turn the attention of its young audience into dollars.

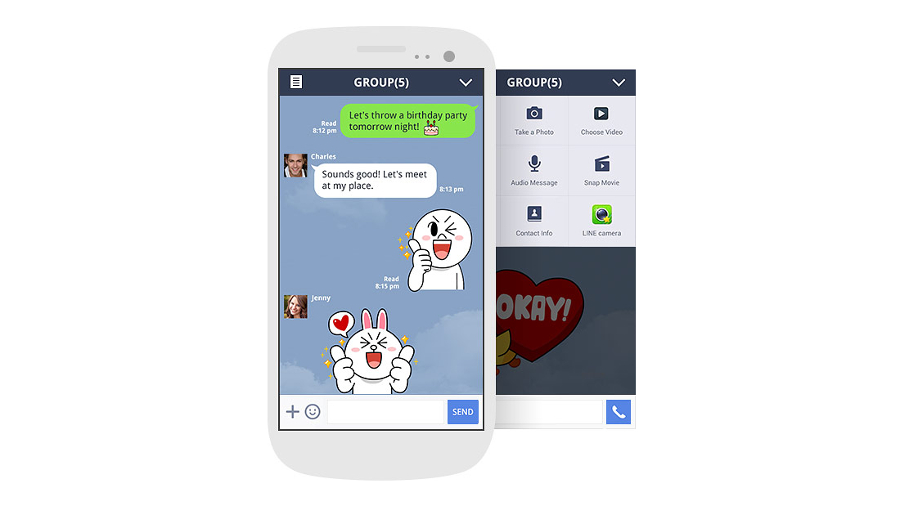

Kik, which is immensely popular with American teens, and Line, which is popular in Asia, are often overlooked, but have tens of millions of users each and are both experimenting with ways to monetise, including branded stickers for topical events.

China also has its own stable of messaging apps, driven in part by the government's general reluctance to let American companies gain much marketshare or influence in the country. Tencent is, essentially, the "Facebook of China" and has multiple apps such as QQ, which has over 800 million users.

The regulations that China puts on companies make it hard to break into the market, but there is one other upcoming super power that has drawn the attention of Silicon Valley: India.

Sights on India

Google, a giant in the U.S. and U.K., is struggling to make a big impact in India with its Android One smartphone initiative as other companies, like Facebook's WhatsApp, take hold. According to Keval Desai, an ex-Google employee, consumers "do all of their communication, commerce, social activities within the walled garden of WhatsApp," which is a big problem if you are not WhatsApp.

Apple has recently been looking at opens its first retail Stores in the country, building its brand in a market that already has 1.2 billion people and is growing exponentially year over year.

It may seem cynical that American companies, driven by profit, are trying to break into these markets but, as Desai says, there services that are provided are valuable. The Times of India, one of the country's national newspapers, published an article looking at how a local business owner uses WhatsApp.

Nanasaheb Sheersat, who is 40 years old, runs a catering business and has used the service to tell clients - many of whom have just recently got a phone - about his wares.

"I did not own a phone earlier. But when I learnt how to use WhatsApp, my mind buzzed with the endless opportunities it presented," he told the Times. "I can spread the word about my products and stay in touch with my customers."

These emerging markets bring their share of challenges too, however. Facebook is looking to invest heavily in "Free Basics," a plan that would bring Internet to India for free but on a limited scale. The company, including CEO Mark Zuckerberg, has been pushing the service heavily, but the Indian government eventually rejected it, believing it would give Facebook too much power over how the Internet was used by millions of people.

This scepticism - which ended up with a tweet storm by a prominent Facebook board member that caused a lot of controversy - shows how hard it can be for Western companies to enter new markets, even if their intentions are largely good.

For Facebook, Google, and others, these markets, many of which are untapped by the big players in the West, are massive. China and India combined have over a quarter of the world's entire population, for example.

Billions of dollars can be made by connecting people, as the story of Nanasaheb Sheersat shows, helping everyday people out in the process.

There is always a chance that the Next Big Thing hasn't even been created yet, especially as the pace of user growth across all sectors increases exponentially, driven by the Internet and availability of apps and services. Snapchat, for example, did not exist a decade ago and is now used by millions

As Google, Facebook, Apple, and Co. dominate the technology world now, messaging, and the industry it has created, could see a new company - whether that be Kik, Snapchat, Line, Tencent, or anyone else -rise to the top.

There are billions of dollars - and as many conversations - at stake, as well as the loyalty of the next wave of Internet users in Asia, which could number in the billions. However, it's still, in 2016, unclear who will win the race outright - and the battle is just getting started.

Max Slater-Robins has been writing about technology for nearly a decade at various outlets, covering the rise of the technology giants, trends in enterprise and SaaS companies, and much more besides. Originally from Suffolk, he currently lives in London and likes a good night out and walks in the countryside.